The LBF in Balboa Park:

Building collaboration among diverse cultural institutions and stakeholders to address shared issues, leverage resources, and align programming for greater impact.

How can funders promote collaboration in multi-institutional settings?

The LBF Governance Model After 2005

Operating Directors. The donor recruits directors that s/he knows and trusts to perform day-to-day administration, establish grant focus, make grants, and to act as operating directors.

Governing Directors. The operating directors recruit a small board of governing directors who have knowledge and expertise in the foundation’s primary grant areas and are familiar with one another. They provide administrative oversight to operations, set compensation, and offer insight to the grants policy and the foundation’s vision.

Spend Down. Establish a spend-down strategy and timeline to distribute the foundation’s assets during the operating directors’ lifetimes. Dissolve the foundation after making dispositive grants in each focus area.

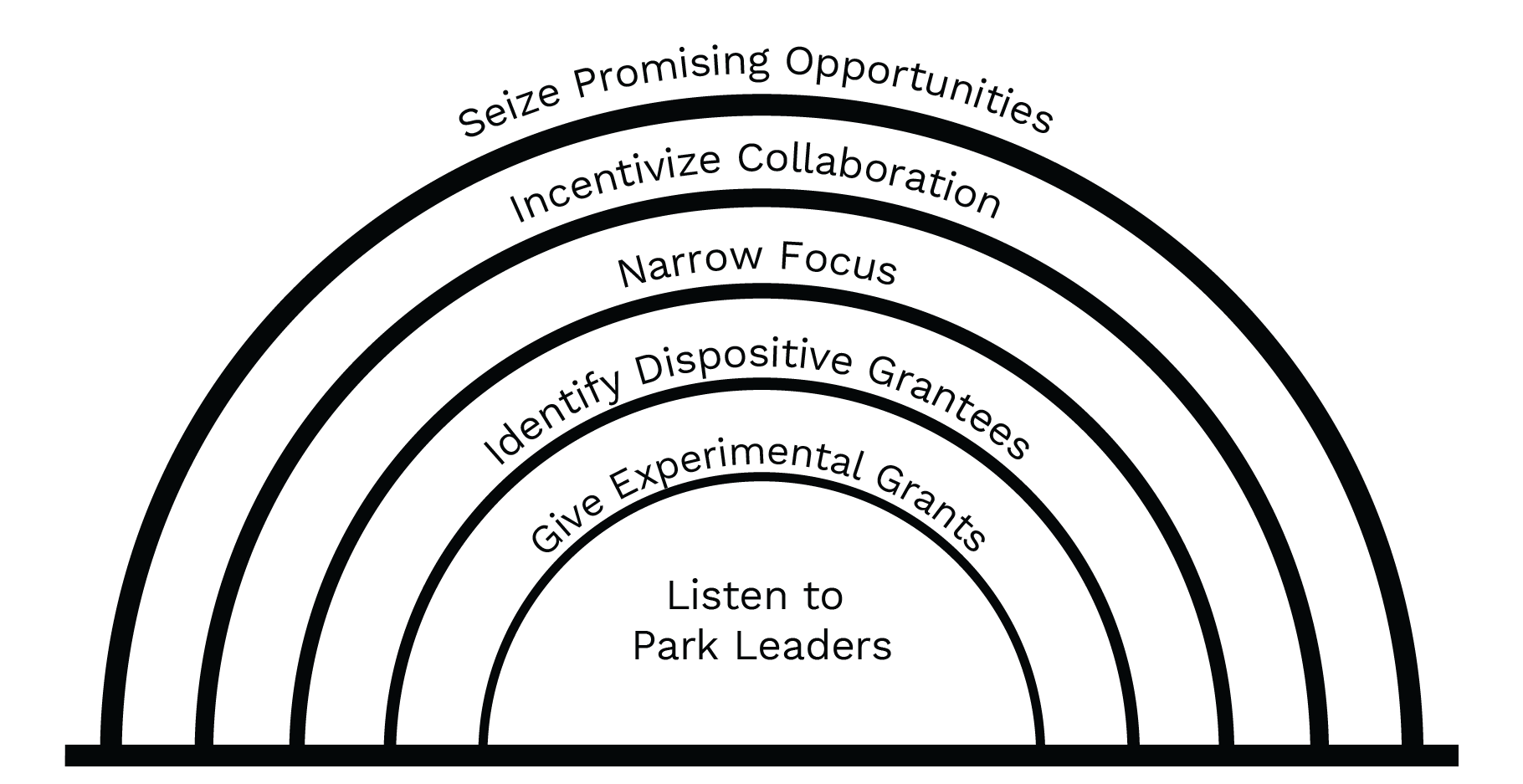

The LBF Grantmaking Model After 2002

Focus and Relationships. Define specific focus areas and establish personal relationships with potential grantees working in each area. Use initial grants to determine the capacity and vision of grantee organizations.

Grantees as Partners. Listen to and learn from grantees. Recognize that the people working in context have the best ideas for addressing the issues in their field.

Collaboration. Work with grantees to refine their ideas and maximize impact. Treat all grantees with respect and admiration for their achievements. Grants recognize the work of the grantees, not the foundation.

Narrow the Focus. Work with grantees to narrow the grants focus over time. Use this process to identify grantees with the strongest records and greatest potential for making significant impact.

Dispositive Grants. Work with these partner grantees to make dispositive grants that will achieve the maximum impact with the resources available. Through this process, spend-down the assets and dissolve the foundation.

This document includes the case study and some, but not all, of the sidebars published on Benboughlegacy.org. Sidebars referenced in this printed document can be found at the end of the main narrative in a section titled Additional Insights - Case Study Sidebars.

About the Legler Benbough Foundation

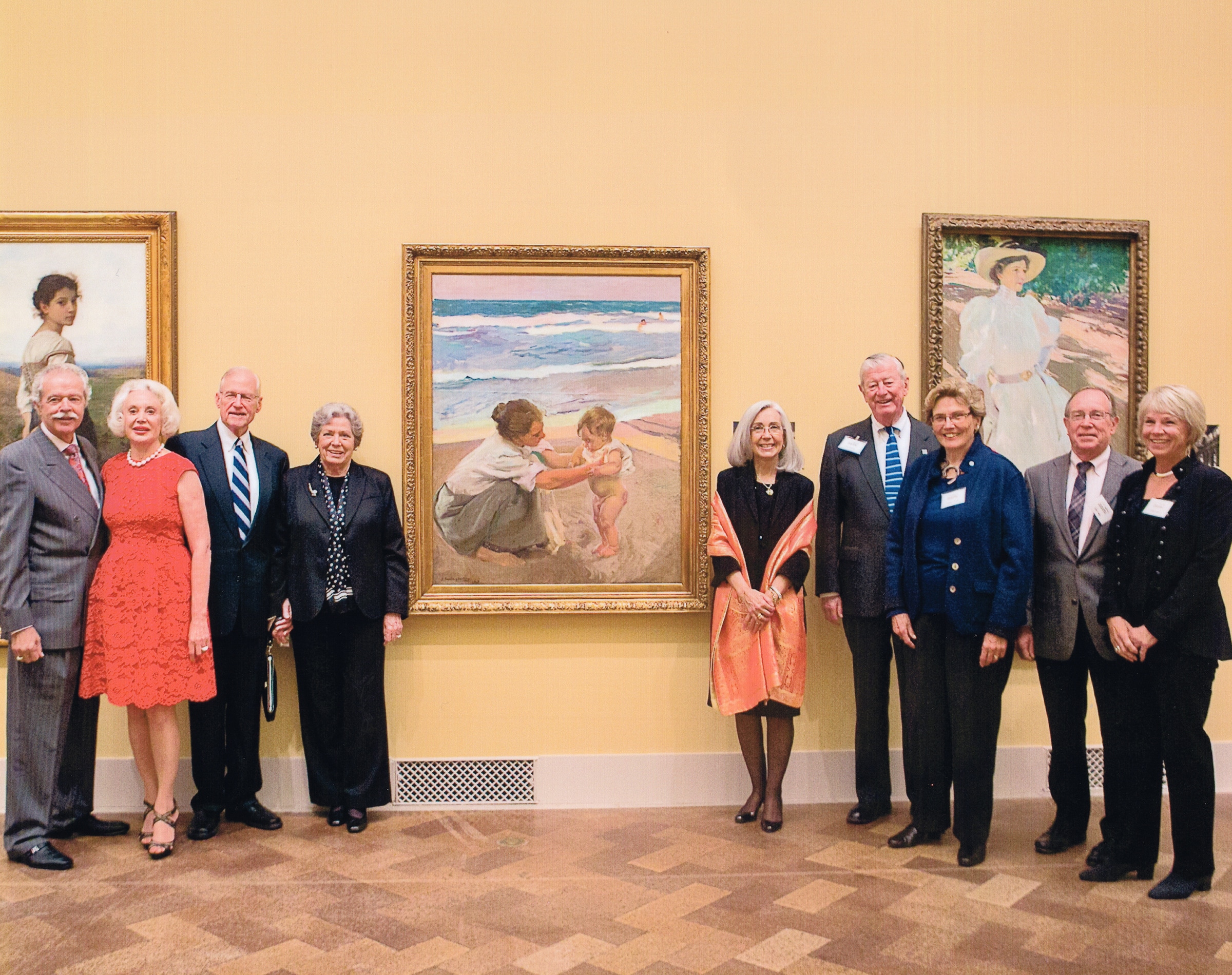

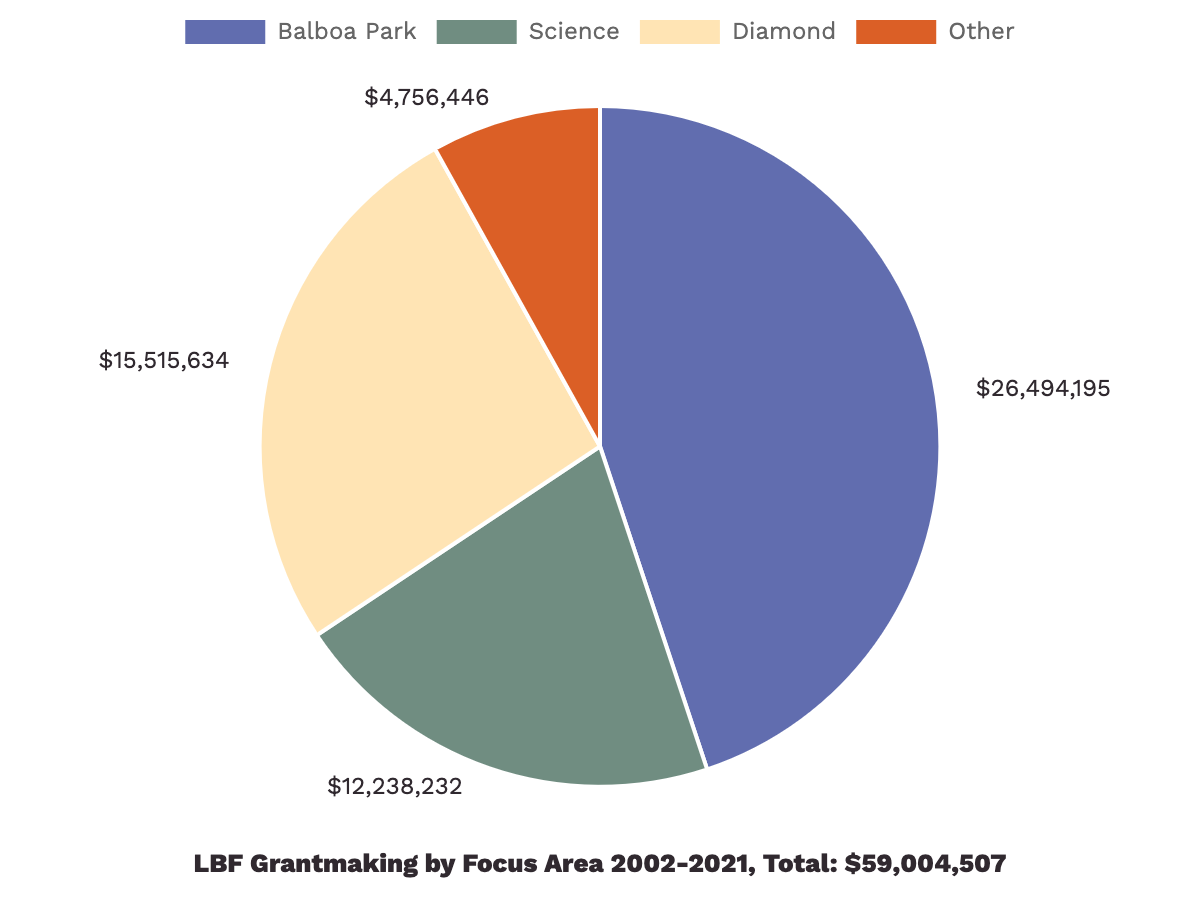

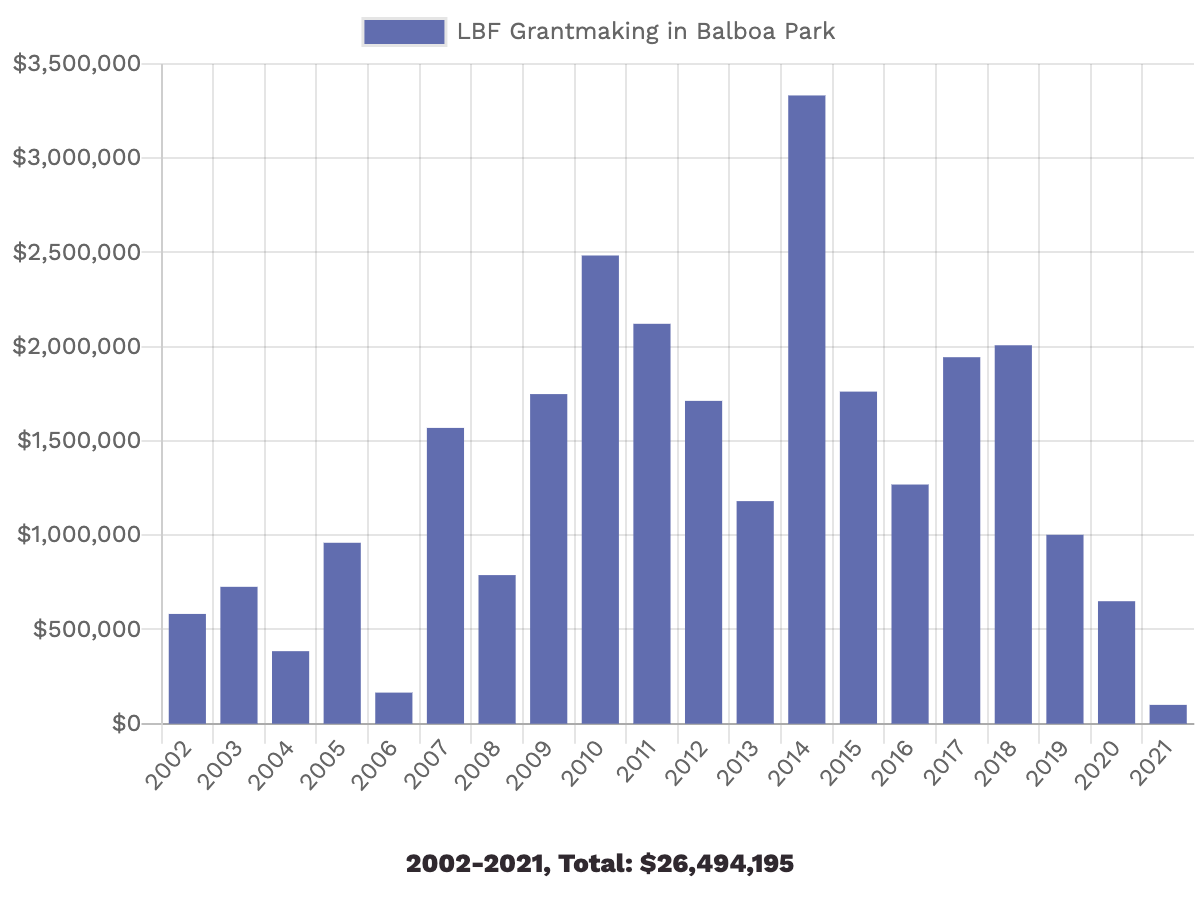

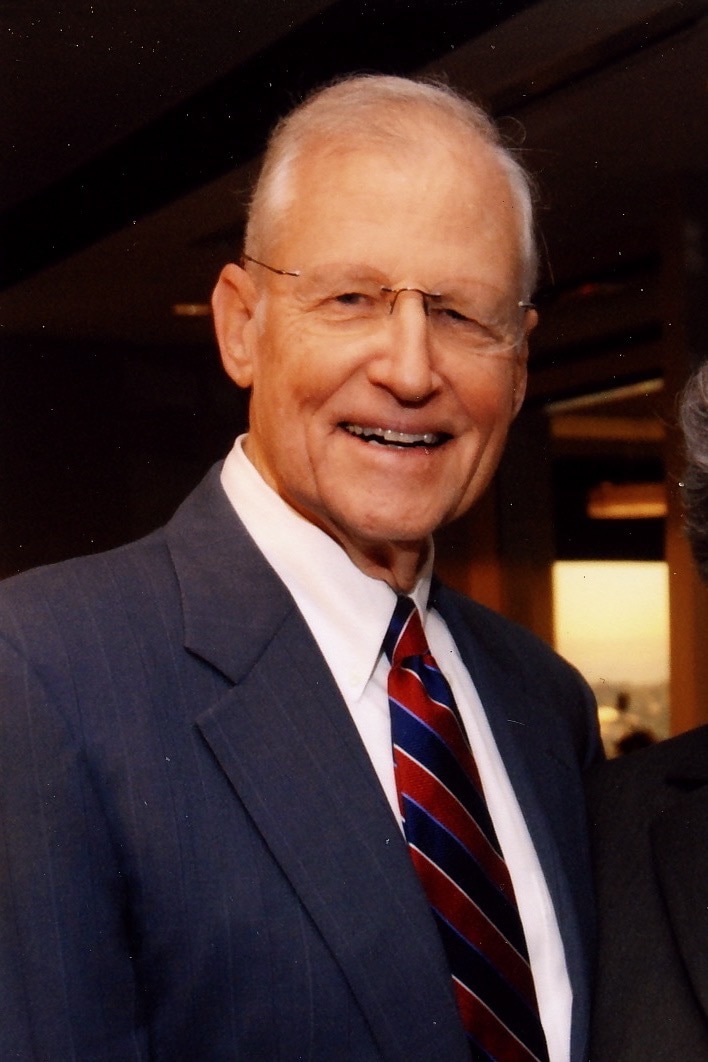

The Legler Benbough Foundation (LBF) was a private philanthropic foundation located in San Diego, California, that operated from 1985 to 2021. During that time, the foundation gave some $66.3 million to organizations throughout the San Diego community. Endowed by a lifelong San Diegan and proprietor of his family’s mortuary business, George Legler Benbough (who went by “Legler”), the LBF funded charitable initiatives of personal interest to the donor from 1985 until his death in 1998. At that time, and at Benbough’s request, two of Benbough’s professional confidants, Peter Ellsworth and Thomas Cisco, assumed control of the foundation. They devised a focused strategy to spend down the foundation’s assets to “accomplish something significant” in San Diego before the end of their working lives and in 2005 recruited a board of governing directors to guide this process.

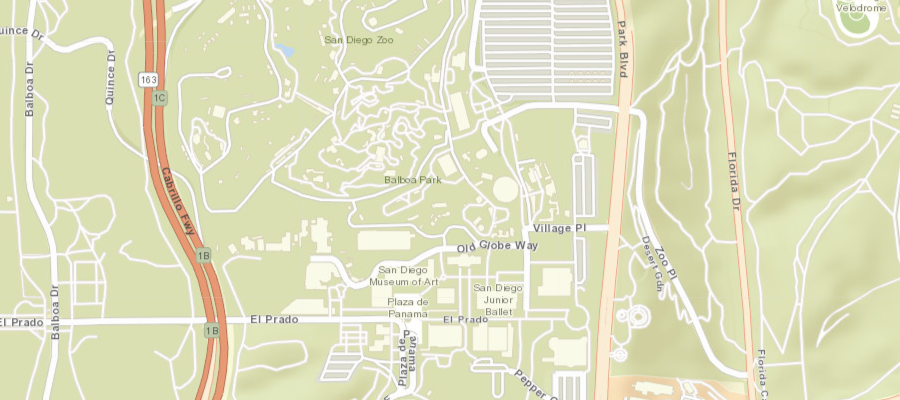

After 2002, the LBF focused on improving the quality of life in San Diego in three core arenas: fighting systemic disadvantage in the Diamond Neighborhoods in southeast San Diego, supporting arts and cultural institutions in Balboa Park, and promoting research and technology development within San Diego’s burgeoning innovation sector as a way to fuel economic development. Given the goal to spend down the foundation’s assets, the LBF’s directors immediately sought to build relationships with grantees in each area—whom they referred to as “partners.” Relying on these partners to identify needs and set priorities, the LBF deepened these relationships and narrowed its focus over time to identify major, dispositive grants that would have a significant impact on the community. These grants were made over several years as the foundation spent itself out of existence in 2021.

In 2017, at the urging of others in the field and as one of its final gifts to the philanthropic community, the LBF engaged Vantage Point Historical Services, Inc. to help the foundation document its history. This work produced four case studies reviewing and analyzing the LBF’s 35-year record of work. Based on research in the LBF’s archives and interviews with the foundation’s directors, grantees, and other partners in San Diego, these case studies provide an overview of the strategies deployed and the foundation’s perspective on lessons learned from its grantmaking in San Diego.

Institutional Collaboration as a Goal

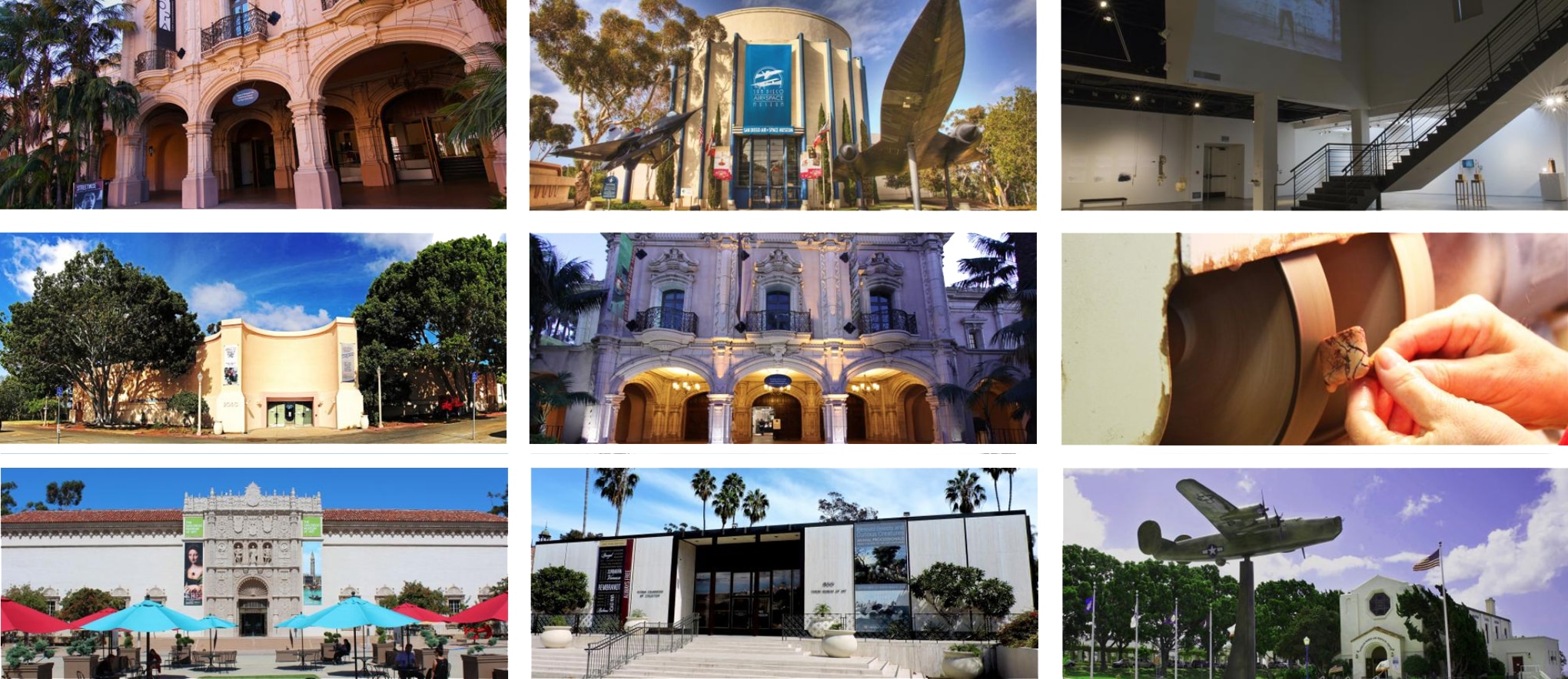

Legler Benbough’s lifelong passion for the arts and culture may have been born during a childhood stroll through the Panama-California Exposition, but it was nurtured over a lifetime by his family’s deep involvement in civic affairs and culture in San Diego. (See sidebar The Donor in case study on Governance.) After his death, the directors of his foundation, Peter Ellsworth and Tom Cisco, believed that strengthening the park’s long-term vitality should be a major priority for grantmaking. Seeing Balboa Park as an iconic asset that enhanced the quality of life across the city, the LBF wanted to help make the park sustainable and help the institutions within it thrive. The foundation balanced support for individual institutions with a broader vision centered on promoting collaboration between dozens of park institutions and stakeholder groups.

The vision for this work emerged in conversations between the LBF’s directors and park leaders between 2000 and 2001. The LBF board invited leaders from Balboa Park institutions to their board meetings to share ideas and concerns with the foundation. Ellsworth and Cisco toured the park, talked over grant proposals, reviewed public data on parkwide visitation and needs, and analyzed the fiscal health of institutions across the park. These conversations allowed the LBF board to develop a focused, relationship-based grant strategy that leveraged the vision of the institutions in the park. (See sidebar on The LBF’s Grantmaking Strategy in Balboa Park).

Between 2002 and its ultimate spend down in 2021 the LBF worked with various institutions in the park, as well as the City of San Diego and other stakeholders, to cultivate and develop the institutional framework for collaborative decision making for systemic change that would leverage the resources invested in the park to enhance its value to local residents and visitors. Along the way, the LBF encountered many obstacles that may feel familiar to funders and nonprofit organizations trying to work within a multi-institutional setting. These challenges included changing political leadership, diverging priorities of individual institutions and supportive entities, and uncertainty over the sustainability of key initiatives.

This case study traces the evolution of the LBF grantmaking process. Over the course of two decades spent working with grantees across the park, the foundation moved from supporting individual museums to funding collaborations between multiple institutions, to supporting projects that were the product of parkwide collaborations. It examines this story through four major projects: the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership, the Balboa Park Online Collaborative, the Balboa Park Conservancy, and the Plaza de Panama project. Throughout the development of these projects, the LBF was deeply engaged in the process of collective conversation. (See Creating Grantee Partnerships in the Diamond Neighborhoods case study.) Peter Ellsworth, as the foundation’s lead grantmaker, listened to grantees and supported group decision making. On occasion, he used the foundation’s resources to push the process forward. Throughout, he sought an ethical and constructive strategy that respected the vision and honored the integrity of his personal relationships with grantees while delivering the greatest impact from the foundation’s grantmaking.

Developing Relationships and Collaboration

The LBF’s work in Balboa Park began during the donor’s lifetime and in its early days was primarily focused on specific grants to individual museums. From 1985 until Legler Benbough’s death in 1998, the LBF followed a passive grantmaking strategy wherein it responded to outside requests but did not articulate a strategic vision. Balboa Park was important to Legler Benbough, and he gave grants to various institutions in the park to support their efforts to promote art and culture. In 1993, for example, the foundation made a $1 million grant to the San Diego Museum of Art to support an endowment campaign—the largest donation to that point in the museum’s history. In 1997, the foundation provided another gift to the Museum of Art to underwrite expenses related to a traveling exhibition of artifacts that belonged to members of the Romanovs, a family of Russian monarchs. After selling around 50,000 advance tickets, park officials expected a surge of up to 100,000 visitors. The LBF’s donation helped cover new security and transportation fees required by the Russian government and played a critical role in bringing the Romanov Jewels to San Diego.

Following Legler Benbough’s death in 1998, the foundation continued to provide grants to individual institutions for another decade. As the foundation’s directors worked to develop a strategy for grantmaking in Balboa Park, these grants honored the pattern of the donor’s giving. Increasingly, however, they provided Peter Ellsworth, as the foundation’s primary grantmaker, with an opportunity to deepen his relationships with institutional leaders in the park and learn more about their common challenges. In 1999, for example, Michael “Mick” Hager, the executive director of the San Diego Natural History Museum (the Nat), explained that “National exhibitions were bypassing San Diego,” because of the lack of adequate space. As a result, the Nat and Balboa Park were missing out on major opportunities to see major traveling exhibitions. To solve this problem, Hager launched a capital campaign to renovate the Nat’s existing floorplan. He presented the LBF with a plan to build a new temporary exhibit hall to bring in major rotating exhibits. In response, the LBF awarded a lead gift of $1 million that enabled the Nat to host many such events over the years. Similarly, given Legler Benbough’s longtime affinity for the San Diego Zoo, the LBF was a major contributor to the “New Heart of the Zoo” initiative, a $28 million renovation project that updated the zoo’s facilities.

The foundation also funded a large artwork conservation and restoration project at the Timken Museum of Art and a variety of scholarship and fellowship programs that brought students, scholars, and artists to Balboa Park, as well as special exhibits at various park museums, including one that explored “black womanhood” at the Museum of Art in 2009. (See Diamond Neighborhoods case study.)

All of these projects with individual museums helped the LBF understand what the institutions in the park really needed and what they had to offer. This kind of personal relationship with grantees and the learning that it provided became the basis for LBF grants in all of the focus areas.

As these discussions in the park with individual museums proceeded and the LBF began to work with the newly formed Balboa Park Cultural Partnership, it became clear to the foundation that the most important resource of all the park institutions was their proximate location. Only by working together could they maximize their response to the opportunities this presented. To further encourage the museums to work together, the LBF changed its grantmaking strategy to support only those projects that involved contributions by multiple museums. This worked. For example, the museums located in one building developed a project to enhance and improve the lobby that they shared to provide better wayfinding and content direction for visitors. Another group of museums worked together when it became apparent that the closure of one major access point into the park could adversely affect them all if they did not work together to encourage visitation. Over time, the LBF further refined its grants criteria to support only parkwide initiatives. This work changed the culture in Balboa Park and achieved the impact of systematic change desired by the LBF.

Key Insights:

As foundations begin to identify partners in a multi-institutional setting, early individual project grants help cultivate trust and a sense of partnership with grantees. Support for capital projects can breathe new life into struggling institutions. Such grants are relatively easy to make, and a donor’s ability to make grant commitments on the spot can create goodwill and trust. Over time, the foundation may see opportunities to support collaborative projects or incentivize collaboration between multiple institutions. Although such collaborations are possible—and funders can successfully incentivize collaboration—this work takes patience, accomplishments arrive slowly, and sometimes, even well-planned initiatives fail.

Study Questions:

How can early, experimental grants help funders understand a new field and identify a strong pool of potential grantees?

How can these early grants support a relationship-based approach to grantmaking?

When working in a complex multi-institutional setting, how can a funder identify and promote opportunities for collaboration?

Dialogue and Learning: the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership

As the LBF surveyed Balboa Park and began developing its new grantmaking strategy around 2001, the directors of the park’s four largest institutions—the San Diego Zoo, the Natural History Museum, the San Diego Museum of Art, and the Fleet Science Center—approached the foundation with a problem. For decades, despite their close proximity and interest in the overall state of the park, the institutions tended to operate autonomously and struggled to work together on common concerns. The four park directors told the LBF that leaders in the park rarely met. Sometimes, institutions blocked each other’s projects. Plans for park improvement were difficult to execute individually, let alone collaboratively. This situation posed a critical threat to the park’s museums.

The effort to try and get us to work together was for me the biggest thing the LBF did for Balboa Park.Deborah Klochko, executive director, Museum of Photographic Arts

The directors asked the LBF to provide the initial funding to create a new nonprofit organization tasked with bringing park institutions together. This entity, they hoped, could coordinate plans, help museums identify administrative overlap, advocate together, and find opportunities to share resources. Over time, such an entity could shift the culture of Balboa Park by encouraging staff to meet often and think broadly about what might work for their institutions and the park as a whole.

In 2001, the LBF committed $50,000 to help launch what was named the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership (BPCP), which over time included 24 park institutions. As the organization worked to secure nonprofit status, it hired David Lang to serve as executive director and help get the BPCP on its feet. Meanwhile, a group of directors, trustees, and senior staff members from park institutions began meeting for a full day each month to discuss shared challenges and opportunities.

At first, Lang was struck by how few park leaders knew each other. During one of the BPCP’s first all-day planning meetings, for example, Lang realized he had to provide everyone with a nametag. This was surprising, he said, because “in some cases the directors worked in the same building.” This problem, as one seasoned executive told him, extended back to at least the early 1990s.

Over the next few years, the Partnership’s member museums explored various ways to share costs. At the request of the LBF, they brainstormed special exhibits revolving around common themes and spread across multiple institutions, giving park visitors the opportunity to get different perspectives on a single, important subject. Park leaders also explored ways to pool their purchasing power and lower costs for products and services ranging from office supplies to insurance. For all their optimism and creativity, however, park leaders soon discovered that it was very difficult to get the buy-in of individual institutions if the collaborative project demanded significant commitments of resources or threatened the internal routines or priorities of individual museums.

Yet these early conversations proved valuable enough to the institutions’ leaders to sustain the BPCP’s momentum. Expanding on the idea of dialogue, the Partnership helped launch an educational initiative to give staff members from across the park a chance to learn about projects other organizations were working on and share insights. All of these conversations, extending over nearly a decade, slowly helped promote a new, cooperative park mindset.

After David Lang left in June 2011, Paige Simpson—a museum professional who had previously worked in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.—served as the interim executive director of the Partnership. Under Simpson, the organization focused on creating an “experience infrastructure” that could bundle different learning opportunities for park visitors, like hosting regular panel discussions on contemporary and historical issues related to the objects, artwork, and interpretive themes discussed at each institution. Simpson also helped create a shared service agreement between park institutions and San Diego Gas & Electric, the local energy utility, that helped museums across the park save money.

Throughout these years, Ellsworth deepened his engagement with the leaders of the park’s institutions and gained a deeper appreciation for the challenges they faced individually and collectively. (See sidebar The Advantages of Personal Relationships.) He listened carefully to their concerns and encouraged them to articulate the vision they had for their individual institutions, as well as the park as a whole. Hoping to change the institutional culture of the park to make it more collaborative and visitor-focused, he pushed hard sometimes, using the LBF’s resources as an incentive. When the Partnership began its search for a permanent executive director, for example, Ellsworth was involved with the recruitment and interview process. When he recognized that the Partnership might not have the resources to recruit a sufficiently talented or experienced leader, he suggested that the LBF could subsidize the new director’s salary, but only if the LBF would have a voice in approving the final candidate.

The LBF encouraged the Partnership to find a candidate who could move beyond education, take advantage of the proximate locations of the park institutions, and promote park advocacy. For the foundation, getting park institutions to focus on raising positive awareness about the park and work together continued to be a priority. With this goal in mind, the Partnership hired Peter Comiskey, the head of Anaheim’s MUZEO Foundation in February 2013. At the time, the organization had about two dozen member institutions, about 15-20 of which seemed actively engaged. Personally interested in strengthening the Partnership’s capacity in business development, Comiskey worked on several advocacy and cost sharing initiatives over the next few years. When the City of San Diego proposed a series of substantial budget cuts in 2017, for example, the Partnership helped lead an “Advocacy for the Arts” drive that limited the cuts. Meanwhile, the Partnership helped drive a campus-wide branding and marketing campaign that involved many stakeholders, not just museums, and also helped park museums arrange and negotiate a cost-sharing program with the local energy utility.

Of all of these initiatives, one encapsulated the Partnership’s ability to cultivate a collaborative idea with resounding benefits for all of the park’s institutions and visitors. Well before Comiskey came to Balboa Park, a group of leaders had envisioned a park-wide membership pass, called the “Explorer Pass,” that would provide visitors access to all the park institutions for a single, annual fee. They hoped the pass would encourage more visitors to return to the park regularly. Some institutions feared that this idea would “cannibalize membership” and drive down revenues for smaller museums. As these discussions continued, the Partnership secured a $1 million grant from the Irvine Foundation to support a feasibility study and forensic accounting review. These studies showed that the Explorer Pass could work and assuaged the concerns of most of the smaller institutions.

By early 2012, the Partnership had requested $2.5 million from the LBF to launch and sustain the Explorer Pass. The LBF, however, had some concerns. Several major institutions resisted the project, fearing that they would end up picking up the tab for smaller museums. In this case, the LBF refused to weigh in on the debate, but suggested that if there was a consensus for launching the “Explorer Pass,” then the LBF would support the concept. “We tried not to get into the middle of disagreements between park museums,” Ellsworth said, choosing instead to allow the directors to work through disagreements on their own. When most of the park’s institutions ultimately chose to pursue the Explorer Pass, the LBF supported them.

When Comiskey arrived at the Partnership in 2013, he spearheaded a plan to use the Explorer Pass as a tool for securing buy-in from park institutions while cultivating goodwill from the broader San Diego community. By purchasing a “Founders Membership,” well-to-do park patrons could choose to buy an Explorer Pass at a higher-than-normal rate, knowing that it would subsidize an additional ten free passes that would be distributed to members of disadvantaged communities across the city. Comiskey and others believed that this strategy would help open the park to San Diegans who, historically, may not have felt welcome in—or simply could not afford to visit—Balboa Park.

Although the Explorer Pass represented an important, parkwide collaboration and promoted goodwill in the community, it did not resolve all the challenges facing Balboa Park. Indeed, the park continued to face an institutional culture characterized by diverging priorities. But, by 2019, the Partnership had matured into a widely-recognized collective voice for multiple park institutions. Its motto, “One Park, One Team,” reflected a new ambition that continued to transform the collective culture of the park’s institutions. With the BPCP available to assemble and coordinate information on the exhibits and events being put on by all its member institutions, the LBF was able to provide a major spend-down grant to fund a joint venture between the Partnership and the San Diego Tourism Authority. This project provided local, national, and international publicity for the park, using data from the Explorer Pass and other sources to target worldwide audiences, providing the kind of impact the LBF desired.

Key Insights:

Although investing in the development of collaborative entities can have a huge impact, promoting cultural change across a multi-institutional setting is a slow, ongoing process. This kind of grantmaking requires funders to constantly make judgments about when they should allow the process to follow its own momentum and when they should use their resources to push or prod organizations to change. Despite its many challenges, and the slow churn of progress when it came to promoting collaboration, the LBF helped create a culture centered around collaboration in Balboa Park. This proved to be one of the foundation’s most broadly supported and attainable goals.

Study Questions:

A relationship-based approach to grantmaking relies on deep engagement with grantees. What challenges does this approach create for the funder and the grantee?

When is it appropriate for a funder to become involved in a grantee’s hiring decisions?

When institutional partners in a major collaboration project have disagreements, how should a funder be involved in resolving the issues?

How can a relationship-based approach facilitate collaboration among grantees? What challenges does this approach create for the funder and the grantees?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of collaboration built through deep engagement by a funder?

Shared Infrastructure: the Balboa Park Online Collaborative

The dialogue that flourished with the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership led to many conversations about potential projects to create resources or infrastructure that would benefit all of the park’s institutions. One early opportunity focused on a film project spearheaded by the San Diego History Center (which was known at the time as the San Diego Historical Society). The History Center came to the LBF looking for funding to support a film on the history of San Diego. The History Center also contacted the Museum of Photographic Arts (MOPA), with which it shared the same building in Balboa Park, and which had recently built a new theater. Realizing that only one adjoining wall separated the History Center’s facility from MOPA’s, the two organizations developed an exciting plan to knock down the wall and allow visitors to watch the History Center’s video in the MOPA theater. This would be the only film on the history of San Diego in town. If successful, the partners believed the project might lead to the creation of a kind of visitor center for Balboa Park, where guests could come, see the film, then get oriented to all the park had to offer.

The LBF supported this initiative and created the Benbough Operating Foundation to manage it. (See sidebar Operating Foundation Provides a Useful Vehicle.) Although promising at its outset, the film project collapsed in late 2005 after the San Diego History Center underwent a reorganization and decided not to pursue the project. The experience offered the LBF an early lesson in how changes at a key partner could doom even the most straightforward, well-financed collaborative. On the other hand, the project also demonstrated how collaborative thinking could lead to truly creative project ideas whose benefits could resonate across multiple institutions and helped feed further conversations among the cultural leaders in Balboa Park.

Like many people who observed the introduction of social media sites like Facebook and Twitter in 2006, or the launch of the Apple iPhone the next year, several museum directors in Balboa Park saw that these tools were beginning to fundamentally change the way people interacted with the digital world and with each other. By about 2008, the LBF began receiving multiple grant requests for digital or IT projects from eager park museums. Many institutions wanted to build a website where they could curate their physical collections and share them online. The foundation funded several of these efforts—like a new website for the Mingei—but knew it could not continue supporting this work on a case-by-case basis. Balboa Park needed a big-picture solution.

To better understand these needs and formulate a plan, the LBF opened a dialogue with David Bearman, a nationally recognized IT consultant. The LBF organized some meetings between Bearman, Ellsworth, and park leaders, which ultimately brought the group to task Bearman with conducting a feasibility study. Bearman’s report described how the development of centralized systems could enhance visitor experiences, create cost-savings, and make Balboa Park a technological leader among its peers. The first step would be to continue building museum websites, expand shared IT infrastructure across the park, and then create a single web portal with access to individual sites and collections. To realize these goals, park institutions would have to commit to working together.

Developing a shared commitment was not easy. Some park leaders questioned the relevance of digital technologies to their work. Others recognized the significance of digital tools, but viewed them as costly and only marginally useful. Some institutions felt protective of their data and were reluctant to expose their operations, even to peers and colleagues within the park. As the foundation encouraged everyone to participate in a new digital program, some park leaders felt the LBF was overstepping its bounds.

Early on, some people felt that Pete had transgressed his role as an outside funder when it came to the BPOC. He applied a little pressure and some people didn't appreciate it. But he was right and ultimately, it worked out.Mick Hager, President and CEO of the San Diego Natural History Museum, 1992-2016

To reassure the collaborators, the LBF made it clear that it would fund a digital program “if and only if” park leaders wanted it. After many conversations between the institution and the funder, a majority of the institutions in the park voted to launch the Balboa Park Online Collaborative (BPOC) at the end of 2008. The LBF provided a three-year, $3 million gift to the Benbough Operating Foundation, which housed the BPOC. This funding enabled the new Collaborative to hire staff, acquire equipment, and get its feet on the ground. Meanwhile, the directors of the BPOC member institutions created an advisory board. Serving on this board and sharing in the decision making gave museum directors a stronger sense of ownership and oversight about the project.

To lead this new initiative, the advisory board recruited Rich Cherry to serve as executive director and build a strategy for meeting the BPOC’s goals and becoming self-sustainable. Cherry had previously worked for major museums in New York and Los Angeles. With Bearman still providing consulting services, Cherry quickly began meeting with hundreds of stakeholders and donors in Balboa Park and across the region. He took the small project team to conferences to expose them to emerging ideas and new technologies. Cherry’s team also organized a variety of workshops to share what the BPOC was doing, get feedback, and learn from other entrepreneurial institutions. As part of an overall effort to accelerate the pace of collective learning, he hosted a content development training for 25 staff members from seven museums across Balboa Park.

The goal was to make San Diego the first city in the world with a completely wired cultural district, a technical infrastructure that allows every member of staff to directly update online information delivered to stationary and mobile web browsers, and provide rich tools to implement e-commerce, multilingual and geo-aware services that will augment institutional missions and bottom lines, and reach new audiences worldwide.Rich Cherry, former executive director, Balboa Park Online Collaborative

Under Cherry’s leadership, the BPOC secured some major, early successes. Among them was the creation of a shared IT platform. For years, another park entity called Balboa Park Central had owned the URL www.balboapark.org, but the page was used only as a static informational website. Leveraging its deep relationships in the park, the LBF negotiated a deal with Balboa Park Central which transferred the website to the BPOC so it could be the central hub through which users could connect to various institutional websites.

Shortly thereafter, the Collaborative created an archival video digitization program, launched dozens of websites and mobile apps for park museums that were accessible through balboapark.org, built a park-wide, high-speed fiber optic network, and blanketed Balboa Park in a public Wi-Fi network. As a result, within a few short years, Balboa Park was recognized across the country for its pathbreaking efforts to incorporate digital technology in museum settings.

These successes came despite deep challenges. Technology evolved quickly, and both the BPOC’s operating model and the LBF’s strategy for funding it were constantly being revised to keep pace. Although the smartphone and social media markets were exploding, the Collaborative came into existence just as the Great Recession rattled the global economy. Most of the institutions in Balboa Park had always operated on shoestring budgets. Directors would have been cautious about investing in new apps and websites in any environment. But the economic crisis exacerbated their concerns over the cost of digital experimentation. Under these circumstances, many park institutions were slow to contribute funds to pay for the IT work BPOC provided, hampering the project’s efforts at sustainability.

Despite repeated calls for stronger support from park institutions, by 2011 it was clear that the BPOC would require additional funding to continue. Seeing the merit of the Collaborative’s achievements, the LBF agreed to extend its funding, but pressed the member institutions to strengthen the BPOC’s internal structure and prevent mission creep.

Given the extra financial strain brought on by the Great Recession, Cherry suggested that BPOC should commercialize its services and look for revenues from outside the park to supplement the fees paid by the member institutions. Meanwhile, he highlighted the potential cost-savings from shared development and the tools that BPOC created. But Cherry’s ideas often ran afoul of the member institutions, as well as the funder.

The LBF directors were concerned that opening the Collaborative to external institutions and sources of funding would let the park museums off the hook and work against the foundation’s efforts to promote collaboration among the park’s organizations. Developing an external client base also threatened to undermine BPOC’s focus and attention to the park. Despite these misgivings, however, as part of its commitment to relationship-based philanthropy, the LBF deferred to the wisdom and the passion of the people on the ground and continued to provide funding for meetings and studies to explore the concept. By the end of 2011, the foundation and the collaborative had come to an agreement: The LBF would make a three-year, $1 million grant. To incentivize the museums to participate in the BPOC, future IT grantmaking would favor institutions that consistently supported the Collaborative. At the same time, the LBF pushed the Collaborative to demonstrate its ability to raise funds to offset LBF grants; convince at least eight park museums to commit to supporting the BPOC under a new, collective management plan; and develop a schedule of deliverables demonstrating its path to solvency.

The Collaborative met each of these conditions and laid plans to transition to a new governance and management structure by the end of 2012. Meanwhile, everyone involved struggled to keep up with the evolving technology and the market opportunities it presented. Despite positive momentum and the reassurance of the LBF’s support, Cherry grew increasingly frustrated. Even though some key park institutions committed their support to the Collaborative, others took advantage of the benefits of balboapark.org and the park’s wireless infrastructure, but turned to the open market for lower prices on IT services, which undermined the business model for the Collaborative. Together, these frustrations convinced Cherry that it was time to move on, and he left in the summer of 2012.

That October, just a few months after Cherry’s departure, the LBF transferred the Benbough Operating Foundation to the BPOC, which then named a new, independent board consisting of seven representatives from park institutions and two park advocacy organizations. Vivian Kung Haga, who had worked at the Museum of Photographic Arts for nine years before serving as deputy director of the Collaborative, succeeded Cherry as executive director. Haga spent about a year helping the BPOC adjust to its new structure and develop plans for the future, but then decided to pursue another opportunity.

Still scrambling to manage these institutional transitions, the BPOC board intended to launch a national search. Its newest member, Nik Honeysett, was a leader in the field of museum technology who was then working at the J. Paul Getty Trust in Los Angeles and had previously been part of a United Kingdom-based digital media firm called Cogapp. The LBF believed that Honeysett had all the skills to lead the Collaborative to the next level, but also understood that BPOC did not have enough in its budget to hire him. Once again, the foundation offered additional support so a grantee could get the leadership it needed. Honeysett was hired in May 2014.

Honeysett understood how the Collaborative could become a vital asset for Balboa Park while remaining a key innovator in the museum world. Like Ellsworth, he saw the tight proximity of the park’s institutions as a unique laboratory setting for developing new, shared tools that could be scaled up to benefit a variety of needs.

To underscore the value of the Collaborative to the museums, the LBF provided seed money for a series of interactive, scavenger hunt-style projects that allowed visitors to seek out items scattered over different museum collections with their smartphones. This approach was designed to present the diverse park museums as a single experience to the visitor. One project played off the popularity of the Harry Potter book franchise and included a “playlist” of items related to the young wizard’s universe. As Honeysett said, Balboa Park had “steam trains, lizards, and old paintings that feel like they follow you throughout the room.” Along with some interpretive content provided by the museums and a little imagination, a visitor could download the Harry Potter playlist and then spend an afternoon bouncing from museum to museum finding these objects. The Collaborative also developed playlists based on holidays and special events, educational hunts created with partners throughout San Diego, and even a “date night” version for young couples.

Overall, these projects led to roughly 300,000 downloads and inspired buy-in from park institutions. Over time, rather than hiring an IT specialist to develop a program or fix a problem as-needed, museums increasingly saw the value the BPOC created when it came to offering on-call, quality tech support and creative content anchored in a deep knowledge of the park’s institutions and their collections.

By 2017—with the LBF signaling its sunset—the Collaborative pitched a data-sharing project as a dispositive grant. At a meeting of the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership, Honeysett had been surprised when one museum director had raised his hand and described how his institution’s attendance had been down for several months in a row, without a clear reason. He asked if anyone else was going through this. Nobody said a word, according to Honeysett, either because they did not want to share or simply did not know.

This situation presented an opportunity to shift the culture in Balboa Park. Rather than having the museums be unaware or self-conscious of their visitation trends, they could learn from one another and get stronger together. BPOC developed a plan to draw park wide, museum-by-museum data from the Explorer Pass program, allowing it to compile concrete information about admissions, membership, special events attendance, and web usage and downloads. This new data tool could help different institutions adjust their business and marketing strategies to maximize attendance and minimize costs. By paying for this data and related services, the museums would also sustain the Collaborative.

The LBF provided funding to help get this innovative plan off the ground. Despite early achievements on the tech side, however, the Collaborative still struggled to bring in sustaining support from park institutions. Once again, the pace of change in the market posed an existential threat to the Collaborative. By 2018 or 2019, all of the park’s institutions understood the value of digital tools, but the tech world was full of low-cost, plug-and-play web services and they could find affordable, easy-to-use web and app design platforms without the BPOC’s help. These commercial providers generally served a larger market and benefited from economies of scale. Moreover, BPOC provided campus-wide services that were supported by revenues generated from the institutions.

Although some of the park institutions appreciated these tools we were building, many of them were less interested in strategy than they were in basic IT capability.Nik Honeysett, Director and CEO of the Balboa Park Online Collaborative

To increase revenues and fill the cost gap between other providers and the BPOC, Honeysett and his team came up with another idea. The data sharing plan in Balboa Park had garnered widespread attention from the museum community nationally. Like Rich Cherry before him, Honeysett and senior members of his staff proposed that they could offer fee-based consulting services to institutions and park campuses in other parts of the country. The diversity of experiences that the BPOC had gained working with park museums, they believed, could be parlayed into revenue to offset fixed costs for the Collaborative.

Once again, the LBF was uneasy with this approach because it would reduce the responsibility of park institutions for the Collaborative’s success and threatened to distract BPOC staff from their core mission in Balboa Park. Honeysett asked the LBF to set aside its reservations and give the Collaborative’s new business model a chance. Trusting that the experts it had brought to the park knew best, the LBF made final grants that enabled the BPOC to develop a clear, pre-developed suite of museum-centric data, web, and mobile tools ready to be implemented by any cultural institution seeking to better engage digital audiences. Meanwhile, Honeysett traveled to conferences, seminars, and consulting sessions all over North America and Europe, spreading the word about BPOC’s work.

By early 2019, these efforts had landed BPOC major consulting contracts with museums in major cities like New Orleans, Seattle, and New York City, as well as in states like Utah and Texas. These contracts bring revenue into the park along with experience and data research that benefits park museums. Meanwhile, Honeysett engaged Microsoft and began a slow process that, he hoped, would culminate in the software giant naming BPOC as its preferred partner, meaning that Microsoft would refer any museum or cultural institution looking for digital support directly to BPOC. All of this work, Honeysett believed, was critical to the Collaborative’s financial sustainability. It also positioned his team at the center of conversations about how the museum visitor of the future would use technology to engage with cultural institutions.

Key Insights:

Although it offered myriad benefits for Balboa Park institutions, their visitors, and peer institutions throughout the museum world, the LBF’s investments in technology development faced challenges. Technology is a rapidly evolving sector with high capital and maintenance costs, changing consumer needs, and shifting markets. Leaders of non-technology driven institutions often fear the costs, struggle to understand the benefits, and find it difficult to recruit and retain expertise. To meet these challenges, while promoting sustained investment in new technologies, funders must adopt a flexible grantmaking strategy that addresses institutional concerns and supports risk-taking.

Study Questions:

What are the advantages and disadvantages of trying to internalize technological expertise in cultural institutions?

How does a collaborative setting compound these issues?

What are the challenges and opportunities that a nonprofit faces when it tries to develop income producing services to support its broader mission?

When a funder invests in the creation of a collaborative, what are its obligations to ensure the collaborative’s long-term viability?

Strengthening Governance: the Balboa Park Conservancy

As the LBF focused on Balboa Park in the early 2000s, the City of San Diego muddled through a series of fiscal and political crises. The City faced serious questions about its solvency, and by 2008, the LBF realized that because the City owned Balboa Park, the foundation was supporting the tenants of a potentially bankrupt landlord.

Peter Ellsworth and Tom Cisco had spent their professional lives in San Diego. They were well connected and knew that, although it would be slow and tortuous, the LBF would need to engage with the City to help the park navigate challenges that had been percolating in San Diego for generations. A stagnant economy had suppressed upkeep at Balboa Park and other community assets in the 1970s and 1980s. Meanwhile, the park fell behind on maintenance and security, tarnishing its reputation and compounding the challenges faced by many park institutions.

In the late 1980s, local leaders assembled a new master plan to clean up the park. By the mid-1990s, many people believed that Balboa Park had turned a corner as municipal leaders courted new industries and companies and the city enjoyed strong economic growth. Balboa Park reaped these benefits, completing many of the goals outlined in a master plan. This growth, however, did not reduce City deficits related to the municipal pension fund. Then, in the early 2000s, a series of corruption scandals led to the resignation of several elected officials, including the mayor. Together, these problems created fiscal and political gridlock that made the chances of strong City support for infrastructure projects in Balboa Park unlikely.

Nobody understood the full scope of deferred maintenance and other facilities issues at Balboa Park. The LBF commissioned a series of studies to help the City gain a clear understanding of the park’s needs. These reports brought clarity and helped the park gain traction as it built support for some major changes. The LBF recruited partners from the Parker Foundation and The San Diego Foundation for further study. In 2008, the foundations commissioned the Center for City Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Lands to provide an overarching view of the park’s needs.

Entitled “The Soul of San Diego: Keeping Balboa Park Magnificent in its Second Century,” the report delivered a troubling diagnosis of the devastating conditions in the park, then presented a series of solutions based on examples from other parks across the country. The institutions in the park, working primarily through the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership, closely monitored the studies and decision making process surrounding their findings. They recognized that with the lack of a clear governance structure, finding a way for parkwide decisions to be made was a huge issue. In response, the Partnership convened a task force of park leaders to evaluate the pros and cons of each solution proposed in the report.

Meanwhile, a mayoral-appointed Balboa Park Committee looked at governance models for the park. Both the BPCP and the Balboa Park Committee suggested that the conservancy model would be the most appropriate and sustainable for Balboa Park. The mayor then appointed a task force to meet in a public forum to reexamine the findings of the two groups and receive public input. They agreed that the park’s governance should be reorganized to become a public-private partnership modeled after those similar to New York’s Central Park as well as other major parks across the country. This entity was to be called the Balboa Park Conservancy.

The LBF contributed significantly to these efforts. Ellsworth attended many meetings and also worked closely with Mayor Jerry Sanders, with whom he had a relationship that extended back many years. Sanders asked Ellsworth to help select the initial organizing committee. This was a unique challenge, given the new entity’s uncertain goals. “At that point,” Ellsworth remembered, “we really did not know just what the Conservancy would do and for that reason, it was hard to determine what skills and experiences were needed.”

The initial organizing committee was formed with the charge to create this new entity and to set it up as a private non-profit organization as described by the task force report recommendations. In 2010, the LBF, the Parker Foundation, and The San Diego Foundation’s Balboa Park Trust Committee provided $120,000 in startup grants to help the Conservancy get up and running, hire a staff, and develop a strategy.

While the objectives of the new Conservancy and the three foundations were the same, differences arose as to the appropriate way to reach those goals. Facing immediate financial and other challenges, the Conservancy deemed it necessary to merge with others in the park, to undertake projects to prove their worth, and to avoid a formal agreement with the City. From the funders’ perspective, becoming involved in these things and failing to have formal City authority made it impossible for the Conservancy to take the leadership role that had been envisioned at the outset. Although the funders believed the Conservancy leaders to be well intentioned, because they did not agree with the direction taken, they chose to cease their involvement and eliminate their funding for many aspects of the Conservancy’s work.

The Conservancy continued to develop its agenda in the park. It provided some funding and enhanced visitor experiences through tours and educational opportunities and encouraged a much-needed emphasis on the horticultural assets of the park. The Conservancy also brought numerous, helpful public forums and data studies to the park, and in 2018, pursued a necessary review of signage across the campus. Since this was exactly the kind of thing that the LBF and other funders wanted the Conservancy to do, the LBF provided the lead funding for that initiative. And, the following year, the Conservancy accomplished other goals, expanding its base of donors and volunteers who contributed to myriad initiatives across the park; continuing a project that planted nearly 600 trees in the park; received major grants from area foundations, the State of California, and the National Parks Service; developed new guided tours and programming to enhance visitor experiences; and more.

While the Conservancy proceeded with these efforts, on the other hand, the City and stakeholders across the park remained generally frustrated by the lack of strategic direction, delay of infrastructural development, and absence of an effective process for making the important decisions required to address these kinds of questions. By the time the LBF was ready to begin its dissolution in earnest in 2019, the LBF had participated in a number of convenings with the Conservancy and other stakeholders to address these issues. But as the foundation committed the last of its funds in Balboa Park, it remained to be seen how the Conservancy would fit into the long-term model for the park.

Key Insights:

Local governments often wield policymaking authority and control assets and resources vital to the success of a public/private collaboration. While funders and nonprofits can commit resources to the collaborative with relative ease, government agencies often face a political dynamic that may pose challenges to the collaborative’s governance and strategy development. Wherever possible, funders should advocate for the creation of a clear governance agreement between public stakeholders and the collaborative (or its constituent grantees) before committing significant resources. Political challenges may also lead the collaborative to shift its mission or strategy toward less ambitious goals that may or may not align with a foundation’s grantmaking priorities. If this happens, a funder will have to decide whether it will or will not remain engaged with the collaborative.

Study Questions:

How can funders use their resources to highlight an issue, bring stakeholders to the table, and encourage public discussion?

What risks and opportunities do funders face when they partner with government?

What issues should a funder consider when choosing to remain or withdraw from a collaborative?

How can funding be used to help incentivize the development of strong systems of governance?

Should funders expect to maintain some level of influence over the decision making of new organizations they help create?

Is it appropriate for a funder to take on a leadership role?

Funding a City Project: the Plaza de Panama

Planned before cars were ubiquitous and placed on a canyon-lined plateau accessible on one side by an iconic and beautiful bridge, Balboa Park did not have adequate parking to accommodate its visitors. As the park continued to develop and attract millions of visitors each year, this problem compounded. It was increasingly difficult for various constituencies—especially older park visitors and those with mobility challenges—to participate in park activities. Additionally, more congestion meant a higher risk of accidents involving pedestrians and cars, and thus, a higher liability for the City of San Diego. With all this in mind, advocates and consultants had been urging park officials and the City to resolve issues related to parking, traffic, and increasing visitation for decades.

Around 2011, the mayor of San Diego, Jerry Sanders, asked Dr. Irwin Jacobs—an engineer who founded the telecommunications giant Qualcomm—to take a look at the traffic situation at Balboa Park. Dr. Jacobs joined the mayor for a private viewing from atop the California Tower at the Museum of Man, which had not yet been opened to the public. Peering out from this high, encompassing vantage point, Dr. Jacobs suggested that the City could divert traffic at the end of the bridge entering the park and into an underground parking structure already proposed in the master plan. This would relieve traffic pressure, remove cars from the center of the park, shorten the walk for pedestrians, and reduce the likelihood of accidents in the park.

Mayor Sanders liked the idea because it accomplished long-sought solutions to park issues and because Dr. Jacobs could provide some preliminary engineering and personal financial support and was well-positioned to secure additional commitments from local donors. Dr. Jacobs championed the $80 million initiative and proposed a 60/40 funding split between the City and local philanthropies. With this, the mayor pledged his support for the initiative, which came to be called the Plaza de Panama project.

The good news is everyone loves Balboa Park. The bad news is everyone loves Balboa Park.David Lang, executive director of the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership, 2001-2011

As Dr. Jacobs built support for the Plaza de Panama project and set about receiving the necessary approvals, he invited the LBF and other funders and park leaders to join the project. According to Ellsworth, many stakeholders supported the project “with pleasure because they recognized that Jacobs’ influence and money might make it possible to address issues of longstanding importance to the park.”

By placing its support behind the project, the LBF complemented a growing tide of strong support for revisions to Balboa Park’s traffic and parking systems. Park leaders and major donors all saw these as among the most critical issues facing the campus and represented the park on the Plaza de Panama Committee. Alongside Jacobs, Ellsworth, and others, they promoted the project and advocated on behalf of city investments in the park throughout the process. The Plaza de Panama project also enjoyed strong political support from the City of San Diego.

A small but vocal constituency within San Diego, however, strongly opposed the project. They raised concerns about the impact on the environment and historical nature of the structures that would be changed by the project, especially the creation of a bypass bridge to take the traffic from the end of the bridge away from the center of the park. Other opponents felt that they had been left out of the decision making process and had questions about park access.

Seeking to resolve these disagreements and bring the project to a successful conclusion, the Plaza de Panama Committee remained open to alternative solutions that could circumvent opponents’ concerns, as long as they could address all the necessary issues. Dr. Jacobs and members of the Plaza de Panama Committee, including Ellsworth, participated in numerous private and public meetings to provide full opportunity for public participation in the process. They also explored all possible alternatives to the plan that would address environmental and related concerns. The meetings were often contentious and accusatory, with members of the opposition making personal attacks on those proposing the plan. Pursuant to California environmental law, numerous alternatives were reviewed with the conclusion that the Plaza de Panama plan was the best option. After many hearings and the completion of the environmental review, the city council approved the project. This vote, which included a positive vote from the councilperson representing Balboa Park, marked an important moment of unity for the City, the major park stakeholders, and the public.

Yet despite the momentum the Plaza de Panama Committee had built, the project’s opponents sought to delay its launch through litigation. To the surprise of almost everyone involved, a trial court found in favor of the project’s opposition, thereby blocking construction from getting underway.

As the stakeholders in the park anticipated, the lawsuit was resolved in favor of the Plaza de Panama project in 2015. At this point, it was obvious to the project’s supporters that it would be necessary for them to demonstrate a renewed commitment and expanded unity of support to convince donors like Dr. Jacobs to continue supporting the effort. Working with support from the LBF, these stakeholders formed Balboa Park United. This group included an expanded network of park supporters, park institutions, and representatives from the planning groups for different sectors of the park. Together, Balboa Park United was the largest single parkwide support organization in memory. As a result, philanthropists and community leaders came together to recommit to the project. Additional funding was pledged in support of the project, including the commitment of $2 million from The San Diego Foundation and $5 million from the LBF. The LBF and Dr. Jacobs, meanwhile, agreed to split the multimillion-dollar costs associated with updating plans to meet changes in laws and regulations related to the project. Then, in November 2016, the city council once again approved the plan with a few minor modifications and put forth a financing plan for the City’s contributions.

None of these developments prevented the project’s opponents from filing two additional lawsuits in December 2016 and February 2017. Attorneys for the City and the Plaza de Panama Committee convinced the courts to end these suits relatively quickly. But, by the time the legal matters had been settled in 2018, the construction costs for the project had escalated significantly. As a result, when the final construction bids arrived in 2019, they exceeded the total cost of the project permitted by the city council in its original approval of the project in 2012. Although these additional costs did not increase the city’s contribution to the project, the project once again required a vote by the council to increase the maximum costs of the project.

Ellsworth, Jacobs, and Jim Kidrick, who chaired Balboa Park United, reached out to the new council representative for the district including Balboa Park—an individual who had come into office during the debate over the project. At the meeting, the councilman surprised the two funders by revealing his opposition to the project. With that lack of support, it was clear that the project would not get the necessary vote of approval by the city council. With this change in the political winds, and despite having invested millions of dollars in engineering studies and litigation, Jacobs and the LBF could not move the project forward.

Overall, the LBF had spent $2.5 million on the project and significantly delayed its spend down as it waited to learn the outcome of the Plaza de Panama project. This was a personal loss for Ellsworth and the foundation.

This experience illustrates some foreboding lessons for foundations hoping to work with city government, or perhaps even any public agency. Inherently unstable political processes endanger the fidelity to long term commitments that major, complex projects require. In government, changes in staff and leadership erode institutional knowledge. In complex projects like the Plaza de Panama, this can leave funders to deal with increased expenses and frustration. In an environment like Balboa Park—where myriad constituencies all have different political connections and supporters—conflict, litigation, and difficult confrontations over motive and intent are likely to occur. In the end, the LBF’s experience left Ellsworth seriously questioning whether a private foundation, and particularly a spend-down foundation, should get involved in projects with public partners.

During the same time period that the LBF was navigating these challenges with the Plaza de Panama project, however, it was able to embrace two special grantmaking opportunities. The foundation’s many years working in Balboa Park had led to deep relationships with leaders at various institutions, including the San Diego Museum of Art and the San Diego Museum of Man (see sidebar Rehabilitating the California Tower).

Key Insights:

Donors can build collaboration by funding infrastructure that supports multiple institutions. Large-scale, long-term projects, however, come with high levels of risk, especially if they involve public agencies. Given the various political and bureaucratic pressures public stakeholders face, they may have difficulty supporting large, multi-year projects. Funders should be fully aware that these forces may doom even the most well-planned, well-financed, and politically well-supported projects. Accordingly, funders must be prepared to walk away from the project or reinvest time and energy when political opposition, litigation, or other threats arise. If funders agree to take on such leadership roles, they become personally involved in public projects and will feel responsible for the positive and negative outcomes.

Study Questions:

Given political uncertainties, under what circumstances should private foundations participate in public projects?

What are the challenges and opportunities a foundation faces when it becomes publicly associated with a project or initiative?

With a relationship-based approach to philanthropy, what are the personal challenges a grantmaker faces when they participate in a highly-visible collaborative?

What lessons can be learned from the Plaza de Panama project about the challenges of community and stakeholder engagement in high profile public-private partnerships?

Additional Insights - Case Study Sidebars

Lessons Learned in Balboa Park

Strategy for Impact: The LBF found that, although rewarding and helpful in many ways, funding individual organizations in Balboa Park could not produce the kind of parkwide impact the foundation desired. To meet its goal of “accomplishing something significant,” the LBF adopted a strategy that focused on promoting collaboration between park institutions.

Collaboration is Challenging: After many years working in the park, the LBF learned that cultural institutions are not naturally inclined towards collaboration. Different organizations face divergent needs, priorities, and agendas. Their decision-making structures, meanwhile, are shaped by different people with different personalities, dynamics, and objectives. Successful collaboration requires individuals and institutions to take risks and reveal themselves to partners. Making this work takes time and patience. And, as the LBF learned, as collaborations mature and leadership changes, partners may not always follow through when it comes to participating in the collaboration to accomplish what was originally intended.

Building Trust: Although it eventually moved away from making grants to individual institutions, the LBF recognized that it was important to fund individual museum projects early on. This was a way to develop deep personal relationships and test the vision and capacity of grantees. These early, experimental grants formed for the basis of the trust that was essential to enabling the LBF to promote collaborations in the park. These relationships also prepared the foundation to work with grantees to develop and change as new opportunities arose and to adapt to leadership transitions and developments outside the park.

Developing a Collaborative Mission: For institutions to make an honest and lasting commitment to a collaboration, they must first develop and agree upon a common set of objectives. Each partner must understand and acknowledge these objectives and recognize them as achievements that no single, individual institution could accomplish on its own. Unless these parameters are clear at the outset, the LBF learned, collaborative partners should not proceed into detailed discussions about how the partners will share responsibilities for the operations, finance, or personnel of the new initiative. And, because circumstances will inevitably change, the collaborative must regularly reevaluate, define, and agree upon updated, feasible objectives upon which all the participants agree.

Stay the Course: Building and working on institutional collaborations is definitely not “feel good philanthropy.” As the LBF learned, it is hard, thankless, and frustrating work. The foundation’s directors often felt personally responsible for failures. They looked back and tried to understand what other paths they could have taken and wondered how different decisions might have created a different outcome. But, in moments of success, the LBF could see the ways in which collaboration in the park achieved things that otherwise would not have been possible.

The LBF’s success creating and working with the Balboa Park Cultural Partnership and the Balboa Park Online Collaborative led to important, positive developments because the foundation was willing to continue to work with the organizations even in moments when the LBF felt the projects had veered off track.

Looking back on its work with the Balboa Park Conservancy, on the other hand, the LBF’s directors wondered whether they should have continued to provide support even after the organization pursued a path that diverged from that which the funders had originally intended. The LBF came to see that funders should think very carefully before abandoning a collaborative effort they played a role in creating.

Funding Public Projects: The LBF learned firsthand the scale of risk that funders assume when they work directly with governmental agencies on large projects. Due to changing political dynamics and the uncertainly of elections, public agencies may not be able to follow through on the long-term commitments of money and political support that many big projects require. Furthermore, the LBF learned that public perceptions of a foundation’s role in the public sphere differ greatly from the way they are perceived in the private sector. Even if initially greeted with open arms by members of the public, as projects continue to develop, foundations may see their support turn to resentment if stakeholders begin to perceive that private donors have unduly influenced the process. To be successful, funders should take extra care to solicit and cultivate public support for any public project in which they are involved. Even then, foundations should expect some degree of pushback.

For these reasons, the LBF completed its spend down wondering whether funders should avoid any public project unless it has overcome all political, regulatory, and legal hurdles, and only requires financial support. And, the LBF learned that foundations with limited lifespans should expect changes and delays in public projects that drag on indefinitely. In the end, the LBF wondered whether spend-down foundations should ever engage in public projects that are still under development.

The LBF’s involvement in Balboa Park did not achieve all that the foundation hoped. Nevertheless, the foundation’s participation helped change the culture within the park’s institutions and provided new opportunities to address major issues through collaboration. In addition, because of the personal relationships it developed, the foundation had special grantmaking opportunities.

Personal Perspective:

Peter Ellsworth

Funding in Balboa Park was very challenging because you're dealing with a lot of organizations and each of them has its own independent mission. Many of them are in tight financial conditions, so they don't have the luxury of time or extra resources to devote to collaborative projects. But there were so many cultural institutions in need in such a small area that we identified it as a place where we could have a big impact. We didn't achieve everything we wanted. But I am proud of what we achieved working together with the institutions in the park.Peter Ellsworth, president and operating director of the LBF

Legler loved the arts and we knew from the beginning that it would be important for the foundation to support arts and culture to help improve the quality of life in San Diego. Balboa Park is unique in its high number of cultural institutions situated within walking distance of one another. It was an obvious and logical place to focus our energies.

Working in Balboa Park, however, proved challenging and complicated. We had to deal with the city government; many organizations with divergent objectives; and strong, passionate leaders everywhere. Although we were focused on working with the cultural institutions, we had to understand how to support them in an environment largely under public control where every blade of grass has its own committee.

At first, we supported museums to which Legler had previously donated. Over time, we expanded our giving and funded some significant projects at museums across the park. It was rewarding in every way and an example of what I call “feel-good philanthropy.”

This work provided the basis for building personal relationships with park leaders, who soon approached us with an idea. They had concluded that by competing with one another rather than working together towards common goals, each museum was failing to meet core objectives. They wanted to establish an organization that would help them work more collaboratively.

The conclusions these leaders reached made sense and led the LBF to fund the creation of the BPCP, our first effort in collaboration. We began to see how, rather than funding ten institutions who were doing basically the same thing, we should focus on cultivating collaborations. This led to the creation of the BPOC and the Balboa Park Conservancy.

Even after we formed these collaboratives, the work was often frustrating. I struggled to understand why park leaders would balk at pragmatic suggestions like purchasing collective insurance or office supplies to save money or not want to work together to curate exhibits on a single subject that would allow visitors to see different perspectives on the subject from different museums all within walking distance. To us, this would create a one-of-a-kind visitor experience. It was frustrating to see museums accept the advantages presented by the BPOC but refuse to pay for the services that made them possible or to watch the Conservancy diverge from the path for which it had been created.

Looking back, I realize that the LBF could have done more to understand the pressures park institutions faced and the sheer amount of time it takes to change institutional cultures, especially at a time when major societal changes affecting the institutions were taking place.

Working with people on a long-term basis, listening to their concerns, and developing personal friendships with them made it possible for us to accomplish many things. But, as a funder who was personally involved in this work, it was critical to balance the objectives of the foundation against the objectives and desires of those we were supporting. Our job was to support the grantees and always demonstrate that “it is not about me.” This, of course, is easier said than done, and I did not always get it right.

Working as a funder in public project development proved to be the most challenging aspect of our work. Being personally attacked and having your motives questioned in a public process is very difficult. Patience is a virtue and has never been my strong suit. It became clear that we did not fully appreciate the magnitude of the risk and public scrutiny we would face while funding in this area.

As in all of our focus areas, the chance to meet and work with amazing, dedicated, and knowledgeable people in the institutions and collaborations we supported was the best part of our work in Balboa Park.

Personal Perspective:

Micah Parzen

It's a shame that the LBF is sunsetting. As frustrating and imperfect and challenging as all those projects the foundation funded were, I think real progress has been made in Balboa Park. That progress depended on having somebody like Peter having an imperfectly guiding hand. As challenging as the work has been for the institutions and for him, the LBF had both the guidance and the resources to back it up. Without that in Balboa Park, what's to keep it from retrenching into a more fractured place?Micah Parzen, CEO, San Diego Museum of Man

People think about Peter Ellsworth and the LBF as a funder. But his impact has been far broader than that. When I came to the park, I had an unusual background as an anthropologist and a lawyer. Peter expressed his confidence early on. He made it clear that he had my back and that he was supporting me. That’s been a huge springboard for me into success.

Some of this had to do with grants the LBF made. Early on, when I came to the Museum of Man, I had no idea how to raise money from private philanthropy. Early on, Peter gave us a couple of really core grants—something like $150,000 for specific projects two years in a row. Those grants were big shots in the arm that boosted our ability to achieve a few goals and envision what was possible. And, of course, the LBF’s help restoring the California Tower was huge. It helped us double our budget and extend our staff based on revenues.

But a lot of what Peter brought to the park had everything to do with his emphasis on relationships. He and some other philanthropists in the community had influence and really pushed everyone in the park by saying “Look, we need to move forward, not backward.” That was part of why he pushed to bring me to the museum. It was just more of a philosophical debate. Do you do more of the same and stay old-school, or do you bring on somebody who can be the future? Peter was very much coming from that perspective throughout his work in Balboa Park.

Peter is a remarkable human being in that he really is able to understand that it’s not about him. That’s not just a line. He really believes it. He also has his own ideas about what will work. He drives them and uses the LBF’s funding as a vehicle. But it’s always been about his kids and his grandkids and the next generation. He thinks about how the park will need to change. How the community we’re trying to serve will change and how folks who are coming of age right now will be expecting a much different experience. Transcending that gap means learning and listening and really envisioning what can change.

There are so many different organizations and perspectives and ideas in Balboa Park. It can be difficult to gain momentum on any idea. But again, as a funder, there’s always this tension. Peter is a big, visionary thinker, and can be critical of the way park directors think. They have all these day-to-day challenges. So, even though he creates genuine contexts where people can give input, sometimes, he’ll say “Well, that’s a good idea, but what about this?” and people go that way because it’s where the funding is.

There’s a dance that goes on. Peter’s not one of those funders who just writes a check. He and the LBF are very involved. They took Legler Benbough’s urging to make a difference with his money very seriously. Over time, their work really has helped change the mentality in the park, and now it’s more of a “rising tide lifts all ships” mindset. I’m concerned about what will happen when they’re gone.

Case Study III Sources

Promoting Institutional Collaboration: The LBF in Balboa Park

“Balboa Park Archiving Content with Front Porch Digital,” GovtVideo, December 17, 2009.

Balboa Park Cultural Partnership, “Helping To Build A Framework for the Successful Governance of Balboa Park,” report presented to the Balboa Park Committee (October 16, 2008).

Center for City Park Excellence of the Trust for Public Land, “Keeping Balboa Park Magnificent In Its Second Century: A Look at Management, Fundraising, and Private Partnerships at Five other Major US City Parks,” August 2006, accessed August 27, 2019, https://www.tpl.org/balboa-park-report-part-i.

Center for City Park Excellence of the Trust for Public Land, “The Soul of San Diego: Keeping Balboa Park Magnificent in Its Second Century,” accessed October 7, 2019, https://www.sandiego.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/park-and-recreation/pdf/bptf/1.thesoulofsandiego-january2008.pdf.

David Garrick, “Arts Groups Demand More Money from City,” Chicago Tribune, May 24, 2017, accessed September 11, 2019, https://www.chicagotribune.com/sd-me-arts-funding-20170524-story.html.

“Dead Sea Scrolls Exhibit Is Extended Into January,” Arizona Republic, December 18, 2007, 11.

“History of the Balboa Park Conservancy,” accessed August 13, 2019, https://balboaparkconservancy.org/about/.

Iris Wilson Engstrand, San Diego: California’s Cornerstone (San Diego: Sunbelt Publications, 2005).

Jack Williams, “L. Benbough mortuary owner, arts patron, dies,” San Diego Union Tribune, June 23, 1998, n.p.; https://www.balboapark.org/itinerary/legler-benbough.

James Chute, “Innovative Online Effort Links Museums and Attractions to Visitors, Each Other,” San Diego Union-Tribune, April 17, 2011.