The LBF Approach

to Governance and Grantmaking:

Building a governance model based on personal relationships with grantees to make the most impactful grants, enable rapid-response decisions, reduce administrative cost, and make the best use of board talent.

How can small, spend-down foundations organize for impact?

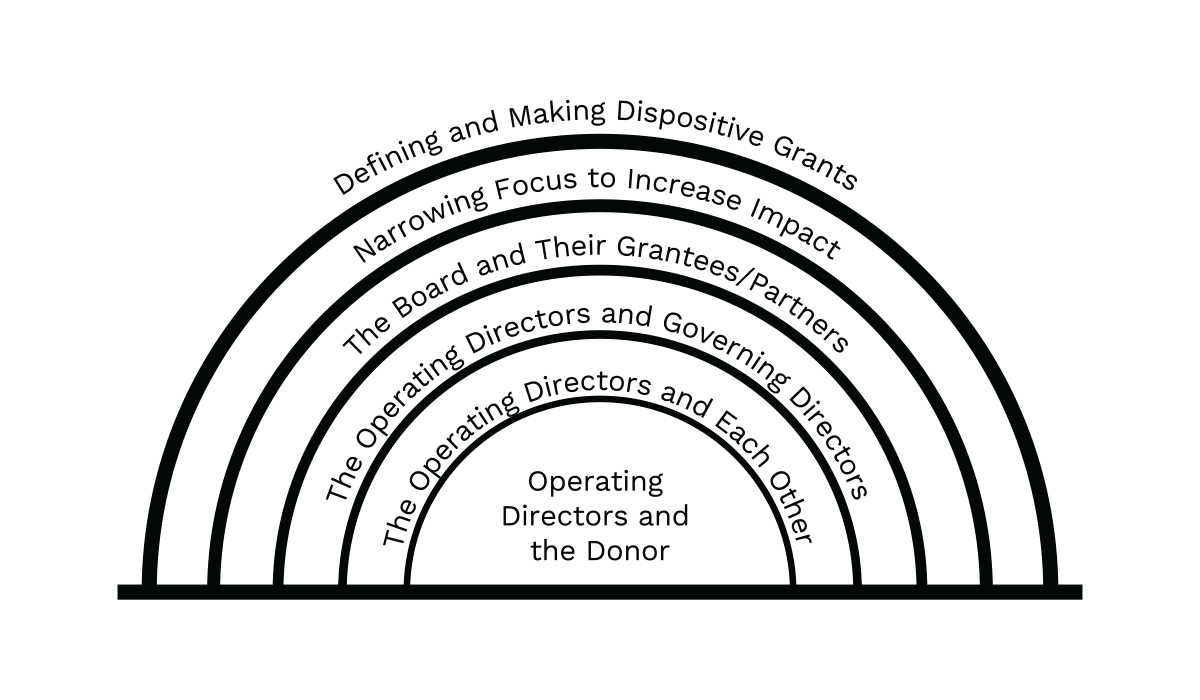

The LBF Governance Model After 2005

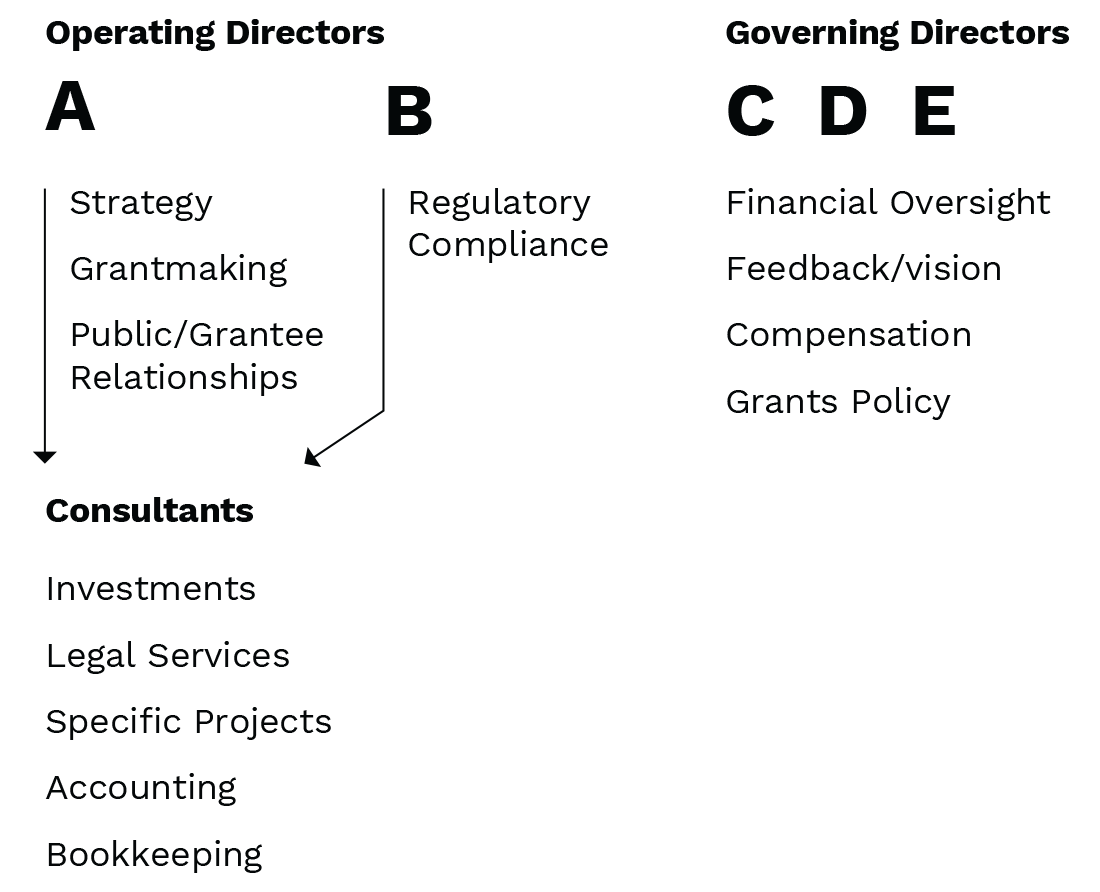

Operating Directors. The donor recruits directors that s/he knows and trusts to perform day-to-day administration, establish grant focus, make grants, and to act as operating directors.

Governing Directors. The operating directors recruit a small board of governing directors who have knowledge and expertise in the foundation’s primary grant areas and are familiar with one another. They provide administrative oversight to operations, set compensation, and offer insight to the grants policy and the foundation’s vision.

Spend Down. Establish a spend-down strategy and timeline to distribute the foundation’s assets during the operating directors’ lifetimes. Dissolve the foundation after making dispositive grants in each focus area.

The LBF Grantmaking Model After 2002

Focus and Relationships. Define specific focus areas and establish personal relationships with potential grantees working in each area. Use initial grants to determine the capacity and vision of grantee organizations.

Grantees as Partners. Listen to and learn from grantees. Recognize that the people working in context have the best ideas for addressing the issues in their field.

Collaboration. Work with grantees to refine their ideas and maximize impact. Treat all grantees with respect and admiration for their achievements. Grants recognize the work of the grantees, not the foundation.

Narrow the Focus. Work with grantees to narrow the grants focus over time. Use this process to identify grantees with the strongest records and greatest potential for making significant impact.

Dispositive Grants. Work with these partner grantees to make dispositive grants that will achieve the maximum impact with the resources available. Through this process, spend-down the assets and dissolve the foundation.

This document includes the case study and some, but not all, of the sidebars published on Benboughlegacy.org. Sidebars referenced in this printed document can be found at the end of the main narrative in a section titled Additional Insights - Case Study Sidebars.

The LBF Approach

Upon its creation in 1985, the Legler Benbough Foundation (LBF) encountered many of the fundamental questions faced by new foundations across the United States. Beyond compliance with legal and regulatory rules, the foundation’s leaders needed to consider big questions about the fate and focus of the organization. What would happen to Legler Benbough’s assets after he passed away? What causes would the LBF’s grants support? Who was best suited to responsibly receive and make use of these funds?

Shortly after Benbough’s death in 1998, the LBF’s directors sought to resolve these questions in ways that would make a lasting difference in San Diego. They developed a grantmaking strategy rooted in personal relationships, focused around a few key issue areas, and committed to a spend down. Although the vision the directors established remained clear from the outset, their organizational and giving strategies evolved to meet the circumstances of the moment. The model they developed and their efforts to leverage it for maximum impact contain lessons for any grantmaking organization seeking to establish or revise its approach to governance.

Trust and Governance in Context

The roles and responsibilities of private foundations have been debated for more than a century in the United States. On one hand, people assert that private philanthropy should be bold and risk-taking. It should reflect the pluralism of American society but should also be accountable to policymakers and the public. Others suggest that philanthropy is an inherently private act. Trustees, they argue, are primarily responsible for carrying out the wishes of donors who should be at liberty to use their assets according to their wishes. Between these two perspectives and within the existing regulatory framework, board members must determine how to govern the foundations they serve.

The mixture of codified rules and regulations and non-codified expectations that shape nonprofit governance have evolved over several generations. This evolution has been shaped by efforts to ensure fidelity to donor intent and to the public interest. It has also been marked by the collaborative and contested relationship between those who lead charitable institutions, benefit from their largesse, and regulate their activities. By focusing on the legal aspects of this development, most books on foundation governance overlook the social context in which governance strategies evolve. In particular, too few scholars and participants in the sector have paid attention to the important roles of interpersonal relationships.

Modern philanthropy developed alongside the corporate form in the early 20th century. Donors who created the largest philanthropies, like the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation, funded large endowments that existed in quasi-perpetuity. They expected their trustees to provide grants from the interest earned on the corpus. In extraordinary circumstances, they might draw directly from the endowment, but this was not the norm. Donors like Rockefeller and Carnegie rejected what was called the “dead hand” of philanthropy. They entrusted to future generations of leaders the power to make grants that could respond to the needs of their time. They did not create proscriptive instructions on how to spend money derived from their assets.

Other groups of donors rejected this approach. Julius Rosenwald—the CEO of Sears, Roebuck and Company who founded the Rosenwald Fund—believed that spending interest off a corpus severely limited a foundation’s capacity to effect change in their lifetime. In an essay in the Atlantic Monthly, Rosenwald asserted that “Permanent endowment tends to lessen the amount available for immediate needs; our immediate needs are too plain and too urgent to allow us to do the work of future generations.” Rosenwald’s approach was adopted by only a small minority of private foundations. After the 1970s, as American conservatives expressed concerns that major foundations like Rockefeller, Carnegie, and the Ford Foundation had migrated too far away from their original donors’ intent, the spend-down approach gained new popularity.

Amid these ongoing debates, thousands of private foundations large and small have sought to develop systems of governance that work for them. They have developed countless models and variations, all aimed at empowering their organizations to meet their mission in a way that honors the culture of their institution with respect to donor intent, responds to the influence of their social network, and incorporates input from various sources. Feedback systems are often critical to governance. Foundations hear from grantees and their communities. Staff members attend conferences and meet with academics and other funders. They read scholarship, reports, and journalism about the state of the field. Together with the inherent personal and collective values of their institutions, all of this information informs the decisions that founders and trustees make about whether to exist in perpetuity or spend down their assets and how to organize their structures and staff to ensure ethical and deliberative grantmaking.

Grantmaking Styles

Passive

foundations inform the public about their philanthropy, accept proposals, and make grants, doing little to evaluate the impact of their giving.

Proactive

foundations provide more detailed information about the kinds of issues they support but do not reject proposals outside their core interests.

Prescriptive

foundations have a defined strategy and act in partnership with grantees as they seek to bring about social change.

Peremptory

foundations send out specific notifications informing grantees of their eligibility for grant funds and carefully manage the work performed in conjunction with recipients.

All this time and energy supports a single, core goal: helping foundations settle on a style of administration and grantmaking that is ethical, efficient, and effective. In order to make sense of the many approaches philanthropic organizations have developed to contend with these issues, philanthropy scholar Joel Orosz developed what he calls the “4-P Continuum.” Along this spectrum, there are four basic styles of grantmaking. Some foundations are “Passive” givers. They provide information to the public about their grantmaking, solicit and receive proposals, and then choose among them. Along the way, they seek very little information from the grantees about the impact of their grants. Other groups of “Proactive” givers provide more public information about the kinds of programs and projects they would like to fund, but do not automatically reject ideas from other areas. Meanwhile, “Prescriptive” foundations are more focused in their work. They have a plan and invite potential grantees to become partners in the process of making social change. The relationship between the grantor and grantee becomes more like that of an agent and contractor. Finally, “Peremptory” foundations push this approach to its logical end. They do not consider general applications for funding, but only responses to their RFPs. In fact, this kind of entity nearly resembles an operating foundation, which is frequently staffed and organized to carry out a specific program. Some foundations choose a strategy that fits somewhere along this spectrum and stick with it. Others, however, move along the continuum as their grantmaking evolves to meet the needs of their grantees or the issues they are working to address. The Legler Benbough Foundation began as a passive grantmaker, but after the death of its founder, it moved very quickly to another model.

The Path of the Legler Benbough Foundation

The evolution of the LBF’s grantmaking can be divided into four major chapters within the broader arc of the foundation’s history. The first phase began in 1985, when Legler Benbough was alive and his foundation existed to manage his giving and serve as a vehicle for passive grantmaking to organizations and issues he cared about. This chapter ended in 1998 with Benbough’s death and the transition to a new era of governance led by the foundation’s two primary trustees: Peter Ellsworth and Tom Cisco.

The second period in the LBF’s governance story followed as Ellsworth and Cisco settled Benbough’s estate and developed a strategy and program for grantmaking. During this period, they developed a sunset strategy aimed at improving the quality of life in San Diego by giving to worthy causes in Balboa Park, the Diamond Neighborhoods, and in the science and innovation sector. The foundation developed grant requirements to narrow giving to these areas, promote collaboration between grantees, empower community members to make changes in their neighborhoods, and assist philanthropic and institutional partners across all three settings.

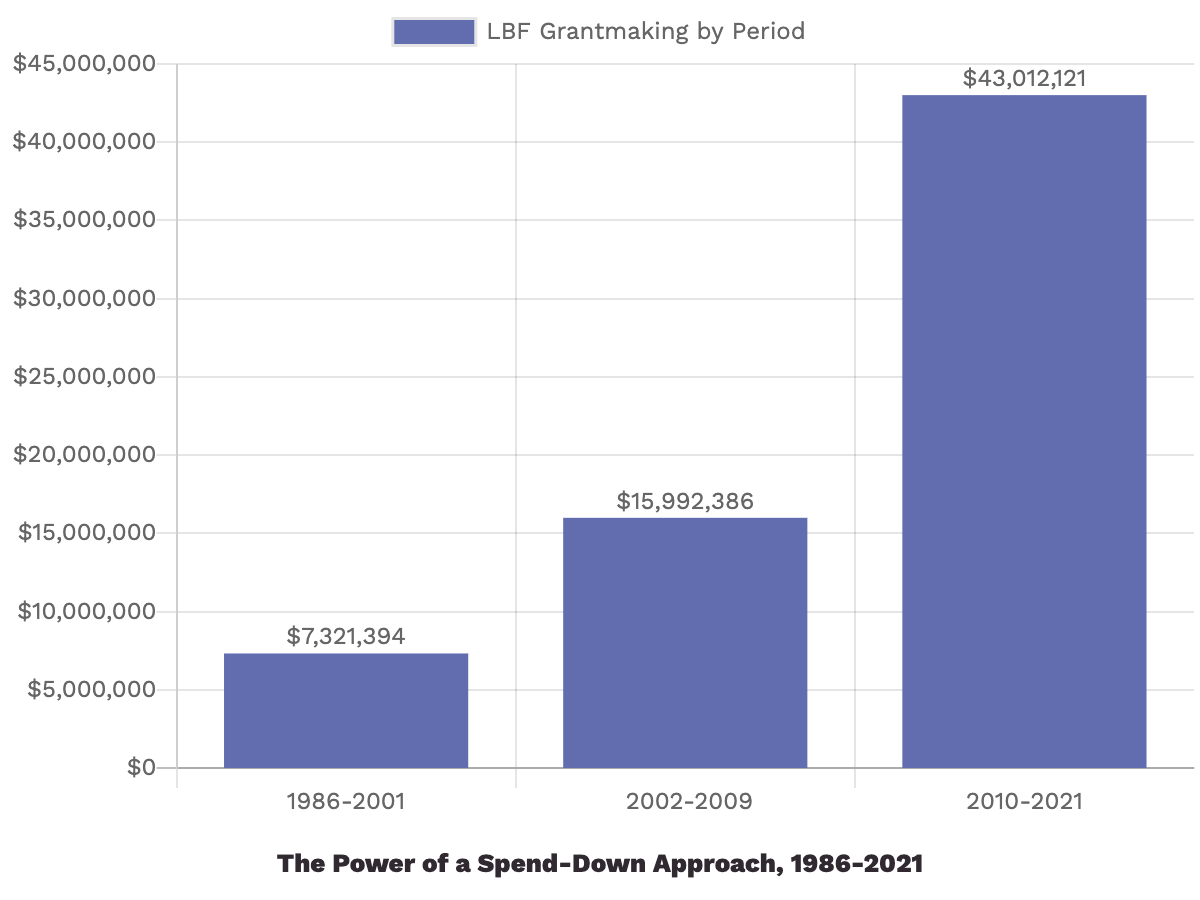

A third chapter began in 2005 and reflected a strategy of iterative or “telescoping focus” within each of the three major program areas. With each round of grantmaking, the foundation evaluated projects and partners. Then it narrowed the focus to deepen its relationships and commitments to those grantees that offered the highest potential for long-term impact. Throughout, the goal was to work with these grantees to identify major dispositive grants and spend the foundation out of existence. (See sidebar How Spend-Down Supported the LBF’s Objectives). At the beginning of this chapter, Ellsworth and Cisco recruited additional board members and worked to refine and implement the foundation’s strategy. They developed an operating foundation as a vehicle for managing certain projects. Meanwhile, the LBF’s directors evaluated what was working in their three focus areas and began drafting versions of the sunset plan that would ultimately lead to the foundation’s dissolution.

The final chapter of the foundation’s story occurred after about 2012, when the LBF’s directors began executing the foundation’s sunset plans by making the first dispositive grants to organizations that had become close partners over the course of the foundation’s work in San Diego. This chapter culminated with the foundation’s final spend down in 2021.

Throughout these chapters, the LBF’s strategy focused on developing deep relationships with its grantees. The foundation listened to grantees, believing they had the best ideas, and it worked with them to develop a shared vision for various initiatives. In working with its grantees, the foundation urged them to take action to carry out agreed objectives and withheld investment when agreed objectives were not pursued. All of these decisions were deeply considered and difficult to make in real time. Ultimately they resulted in a novel approach to institutionalized private philanthropy. The story that follows tracks the LBF through these major turning points, highlighting lessons for donors, funders, and nonprofit professionals along the way.

Creating the Foundation

Many people knew that Legler Benbough had money and they were not shy about asking him for help. One night in 1984, however, he arrived home to find a grantseeker lingering outside his home, hoping to make a pitch. Frustrated, Benbough called his attorney, Peter Ellsworth, and said “this has to stop.” At 75 years old, he wanted a better way to manage his philanthropy. (See sidebar The Donor.)

Ellsworth understood. He had spent years working to support arts and cultural organizations across San Diego. He had been involved in the creation of the Committee of 100, a group dedicated to preserving the Spanish colonial buildings in Balboa Park. In 1983, he was elected president of the Combined Arts and Education Council of San Diego County (COMBO), a leading organization that raised money for a variety of arts and culture organizations in the region. He knew how desperate some of these organizations were to cover their operating costs and carry on their work on behalf of the community.

Ellsworth helped Benbough create the Legler Benbough Foundation. That way, Benbough could fund the foundation when he needed the tax write-off, direct grant seekers to the foundation, and give at his leisure as long as he met the government’s 5 percent distribution requirement. Benbough also asked Ellsworth to redraft his will so he could designate most of his estate to the LBF. With cash contributions beginning in 1985 and augmented in 1986 with the proceeds from the sale of his ranch property in Rancho Santa Fe, the initial corpus of the foundation rose to $3.8 million at the end of 1986.

Benbough called Peter all the time about the foundation, about his estate, about everything.Bob Kelly, former president and CEO of The San Diego Foundation, LBF governing director from 2013-2021

Trust & Donor Intent

As with all corporations, the government required Legler Benbough to name a board of directors. Lacking any heirs or close family, Benbough chose people he knew and trusted. Peter Ellsworth had been his attorney for years. (See sidebar The Lawyer.) Tom Cisco was Benbough’s long-time banker. (See sidebar The Banker.) Benbough also asked a wealthy friend from La Jolla to round out the board, and when she stepped down after a few years, he invited Miles Pelky, a long-time employee and friend, to serve.

For the first decade or so of its existence, the LBF was a passive grantmaker. After a friendly lunch, the directors reviewed requests and made grants. Through the early 1990s, grantmaking averaged approximately $215,000 a year. Most grants were for $5,000 or less to organizations working in a wide variety of arenas. These multiple small grants often reflected the charitable interests of various board members. There were two major grants in this period: one to the San Diego Museum of Art to reflect Benbough’s long standing support for this institution, and another to Sharp Health Care Foundation to honor Benbough’s mother. These two grants accounted for 52.2 percent of all the $1.8 million awarded by the foundation between 1986 and 1995. Over time, however, this process of unfocused grantmaking frustrated Benbough, and he turned to his closest advisors to develop a different approach.

Ellsworth and Cisco had the right personalities and skills to help the donor plan his giving. Even after Ellsworth resigned from the LBF board in 1986 to become CEO of Sharp Health Care, Benbough continued to reach out to him for advice and counsel. In 1991, when Benbough created a living trust, he named Ellsworth and Cisco as his trustees and executors. And after Ellsworth retired from Sharp in 1996, Benbough encouraged him to rejoin the LBF board.

Nearing the end of his life, Benbough talked to Ellsworth about how he would like his estate used after his death. He pressed Ellsworth and Cisco to run the foundation after he was gone. Ellsworth and Cisco, however, were not sure they wanted to take on this work. Each was enjoying a well-earned retirement. Serving part time on a board chaired by a living donor was an easy commitment. But as Benbough’s health began to decline, it became clear that he wanted a more robust and targeted strategy after his death, an effort that would demand far more time and energy.

Over the course of a series of conversations from 1996 until the time of Legler Benbough’s death in 1998, including a deposition with a court reporter, Ellsworth and Cisco tried, without success, to elicit Benbough’s vision for specific grants from the foundation. Although he was vague about the exact causes his money should support, these conversations resulted in an increasingly firm concept of how the foundation should operate.

Above all, Benbough wanted the foundation to “accomplish something significant.” He said, “I don’t want to give $10,000 to everyone in San Diego and not accomplish a damn thing.”

Benbough did not want the LBF to exist in perpetuity. He wanted the money spent during the lifetime of Ellsworth and Cisco. He believed that perpetual organizations become risk averse. He had also seen foundations created by some of his friends gravitate to projects and concepts totally adverse to those of the original donor. Moreover, he felt that his wealth could have a greater impact if its resources were expended in bigger amounts over a shorter time horizon.

When Ellsworth suggested that the board would have to be expanded to tackle this vision and manage a larger pool of assets, Benbough encouraged him to wait until after Ellsworth and Cisco had established a giving strategy describing the areas of the foundation’s focus for grants. At that time, Benbough believed, the board should have members that supported and had experience in the areas the foundation intended to fund. Otherwise, the board risked losing focus and could end up following the passions and interests of the individual directors.

Finally, Benbough insisted that the foundation staff, Ellsworth and Cisco included, should be paid reasonable compensation for their services. It was his view that compensation is essential to provide the incentive for the dedication and time that would be necessary to do the job that he contemplated.

The only specific advice Benbough provided to Ellsworth and Cisco was that he was not interested in public recognition. In fact, Ellsworth remembered Benbough laughing as they discussed this issue and remarking that “if I see my name on one more thing, I’m going to be sick!”

Reflecting on these conversations, Ellsworth suspected that Benbough was deliberately vague about grantmaking in order to give Ellsworth the freedom to develop the program, something that would make him much more interested in taking on the job. Most importantly, however, Benbough knew the integrity of both men and trusted them to work together to maximize the impact his assets could have on the San Diego community.

Key Insights:

Although governance is defined by the legal system, informal relationships between donors and their trustees play a major role in shaping the character of a private foundation. Donors like Legler Benbough rely on these personal relationships, as well as formal statements and documents, to ensure that their donor intent is fulfilled. Not all donors have a strong programmatic vision for grantmaking, but they may have very strong ideas about how they want their foundation to operate, including whether a foundation is intended to spend down its assets or exist in perpetuity.

Study Questions:

Why would a donor prefer a spend-down versus a perpetual foundation?

Should the decision to spend down the assets affect the way a foundation is governed?

What attributes should a donor look for in choosing directors for a spend-down foundation?

What are the arguments for and against compensating directors of a private foundation?

Defining the LBF’s Operating Principles

Even though Ellsworth and Cisco knew the 88-year-old Legler Benbough’s health was in decline, his passing in June 1998 came as a surprise. As his executors, the men spent the next two years settling Benbough’s estate by selling his assets, including his beachfront home and art and memorabilia collection. They donated items like Percy Benbough’s parade saddles and other antiques to area museums, using tax benefits and proceeds from these gifts and sales to build the LBF’s asset base. Meanwhile, the LBF continued to make grants in a familiar pattern.

As this estate settlement process wound up, the LBF evolved from a passive giver to a more proactive model. With a substantially larger asset base of about $40 million, Ellsworth and Cisco established a model for governance and operations, based on Benbough’s thinking, that would maximize the impact of the LBF’s gifts. Having just finished long careers as corporate executives, neither director was interested in managing people or dealing with personnel issues. To conserve energy and limit overhead, they agreed not to hire a staff. If they needed expertise, they would hire consultants. Relying on an independent firm to conduct a compensation study, they set reasonable salaries for themselves and moved into Benbough’s office.

The LBF’s approach to governance and operations relied on the compatible personalities and complementary skillsets of the two directors. While the two directors worked together on strategy and policy for the foundation and consulted each other on all matters of significance, they divided their day-to-day operational roles on the basis of their past experience and interest. Honed over a long career in banking, Cisco’s mind focused on finances and details. He had been managing the LBF’s accounting and assets since 1985. Under the new arrangement, he continued to handle bookkeeping and cashflow, supervise consultants, and work with an outside investment advisor to steward the foundation’s assets.

Pete didn't treat grantee organizations as if they didn't know what was going on the way some grantmakers do.Bob Kelly

Ellsworth, on the other hand, became the public face of the foundation, attending meetings, developing the foundation’s program and strategy, making grants, and discussing potential grantee organizations with Cisco. Ellsworth had extensive experience and a broad skillset. He had spent decades in community affairs, including civic groups like the Rotary Club. Working in nonprofit law as an attorney and as CEO of a $1 billion nonprofit corporation had given him an understanding of the field and experience managing a huge enterprise that employed people from a wide variety of backgrounds. He was engaging, affable, and curious and enjoyed networking and attending meetings and events. He paired all of this with an abiding commitment to improving San Diego. Like many new foundation executives, he had little formal training in philanthropy, but he believed he would learn by listening to other funders and grantees.

Key Insights:

Most private foundations in the United States do not have full-time staff. Like the LBF, many rely on directors, who are often closely associated with the donor, to oversee grantmaking and outside advisors to manage investments, accounting, and compliance. The capacity of small foundations to do strategic grantmaking is often limited by the experience and skills that the donor and his or her directors bring to the foundation. Relying on a relationship-based governance model, the Legler Benbough Foundation was able to minimize paperwork and overhead by giving one director authority for grantmaking and the other responsibility for finances. This approach required high levels of trust.

Study Questions:

How did the experience and expertise of the LBF’s directors shape the foundation’s approach to governance and administration?

Under what circumstances is all or part of the LBF model replicable?

What are the advantages and disadvantages in choosing board members with similar backgrounds and well-established relationships with one another?

What are the challenges created by a relationship-based approach to accountability and transparency in grantmaking?

To what extent and under what circumstances can the grantee relationship model of the LBF be used by other foundations following a different model?

How did the LBF model balance the private wishes of the donor with accountability to policymakers and the public?

Developing a Strategy for Grantmaking

Legler Benbough had entrusted Ellsworth and Cisco to make their own grant decisions, telling them only that they should use his assets to “accomplish something significant” in San Diego. With just over $40 million in assets, the LBF was a significant, but not major, player in the broader ecosystem of San Diego philanthropies. (See sidebar Philanthropy in San Diego.) Therefore, to “accomplish something” the directors needed to develop a focused style of giving and a strategy to support it.

Since 1985, the LBF’s mission had been “Improving the quality of life for San Diegans,” but this was too broad. About a year before Benbough’s death, Ellsworth looked at the foundation’s pattern of grantmaking and proposed that the foundation focus on youth programs, education, civic projects, arts and cultural institutions, and the San Diego Zoo. Benbough would not engage with Ellsworth’s proposal. After Benbough’s death, Ellsworth and Cisco embarked on their own effort to define a strategic plan for the grant areas in which the LBF would focus.

Ellsworth began attending meetings with other donors in organizations like the San Diego Neighborhood Funders Group and the Arts and Culture Working Group at The San Diego Foundation. He also participated in the Strategic Roundtable and the Chairman’s Roundtable of the San Diego Regional Economic Development Council and served on the advisory board of San Diego Grantmakers.

The original mission of the foundation, in place from the beginning, 'Improving the quality of life for San Diegans,' was far too broad to have any meaningful impact with the resources and the time that we had.Peter Ellsworth

After these meetings, Ellsworth shared what he was learning with Cisco. Over time, they discerned that in order to focus their grantmaking, the LBF would need to develop both thematic and geographical boundaries and then stick to them. Given the Benbough family’s history in San Diego and their own deep knowledge of the community, they decided to limit grantmaking to organizations within city limits. Thinking about what specifically was necessary to accomplish the original mission of Benbough and the foundation—“Improving the quality of life for San Diegans”—Ellsworth and Cisco settled on three areas: arts and culture; health, education, and welfare; and economic opportunity.

Ellsworth and Cisco understood that this was still a broad mandate. Over the next several years, the foundation used its grants to begin to explore various potential program areas and develop relationships with grantees and other funders. It made small experimental grants to test ideas and observe how effectively organizations used their funding. These grants and conversations helped narrow the focus.

In the realm of arts and culture, Legler Benbough had always been particularly interested in Balboa Park. The park and its cultural institutions embodied much of the history of the city and had long been a crossroads for the city’s many different communities. Many of the individual institutions in the park, especially the art and history museums, appealed to Legler Benbough’s own passions. So the park emerged as a focal point for arts and culture grantmaking. (See Balboa Park case study.)

Health, education, and welfare was a little more difficult. During Benbough’s life, the LBF had made grants to various hospitals as well as local and national organizations battling particular diseases. Additionally, the foundation often received applications from groups working to assist the elderly, youth, and disadvantaged people across the city. These efforts, however, felt too diffuse. The LBF’s directors saw that their limited resources could not make a significant impact across the entire city, so they focused more narrowly on the historically disadvantaged Diamond Neighborhoods in southeastern San Diego for their health, education and welfare funding. (See Diamond Neighborhoods case study.)

Identifying parameters to support the LBF’s third area of interest, developing economic opportunity by supporting San Diego’s technology and innovation sector, was even more challenging. Simply put, the foundation’s resources were dwarfed by the huge investments of philanthropists, entrepreneurs, investors, and federal research grants. Around 2000, San Diego’s innovation economy was exploding, with the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) at the center of this activity. As in each focus area, the LBF began its activities by using grants and personal connections to understand the landscape for potential grantmaking and how a foundation of the LBF’s size could make a difference. They settled on an initial strategy focused on recruiting and developing talent, supporting collaboration among institutions, and nurturing community support for science and innovation. (See Science & Innovation case study.)

Ellsworth and Cisco formalized the foundation’s grantmaking strategy around these three focus areas in July 2002. They created a list of grants criteria and then made them available to people and organizations in each of the three program areas. The two men recognized that some of the foundation’s existing grantees would not fit within this new strategy, but most of these institutions were receiving only small grants. With the exception of Sharp Health Care Foundation, which would no longer be a strategic partner, other major long-time grantees would be folded into the new strategy. (See sidebar The LBF’s Governance Strategy.)

Key Insights:

Philanthropists and foundations face social pressures to give widely, but they can have more impact if they give in a focused strategic manner. Strategy should reflect a synthesis of the donor’s intent in combination with a disciplined assessment of what can realistically be accomplished. In the early stages of developing a new program, many small grants allow a funder to develop relationships with people working in the field and learn from them to refine an effective grantmaking strategy. With fewer decision makers, a foundation can develop its strategy more quickly. To avoid the risk of tunnel vision, the strategy can be tested with outside advisors including other funders, grantees, or policymakers.

Study Questions:

How does the decision to spend down the assets of the foundation affect the strategy for grantmaking?

Are some grantmaking arenas better suited to a spend down?

What are the benefits of narrowing the focus to a small number of program areas? What are the risks in this approach?

As a foundation narrows its focus, what responsibility does it have to prior grantees who may no longer receive support?

A Relationship-Based Approach to Grantmaking

With program areas defined, Peter Ellsworth, as the LBF’s grantmaker, began working in earnest. He had received all sorts of advice about how to work with grantees. Other funders or organizations of grantmakers counseled him to develop a buffer between the foundation and its grantees. Others advised the foundation to limit gifts to specific organizations to prevent them from becoming dependent on the foundation’s resources. Quickly he sensed an aloofness in the field that underscored the imbalance of power between people and organizations who needed help and entities that had resources to distribute.

I had discovered a long time ago that the five most important words you can utter are 'it is not about me.' If you want to engage others to get something done, the focus has to be on the project.Peter Ellsworth

Ellsworth intuitively rejected much of what he heard. As a CEO he had learned that the best ideas came from the people who were closest to the work. If you didn’t talk to people to understand their vision, their challenges, and their opportunities, it was difficult to assess what was possible. Between 2002 and 2005, Ellsworth spent countless hours in meetings and site visits with potential grantees, nonprofit directors, and civic leaders in all three areas. He relied on Cisco as a strong sounding board, and together they considered Legler Benbough’s interests and priorities.

As Ellsworth focused on what he would later call a relationship-based approach to grantmaking, it seemed to him, in working more closely with the grantees, that many of the traditional foundation grant strategies were creating the wrong relationship with grantees and preventing the kind of relationships that were essential in working together for mutual success. Ellsworth had learned over the years that projects and initiatives were more likely to be successful if he was willing to accept the principle “it is not about me.” In the case of the foundation, it was about the project and the people the foundation was trying to help. Building authentic grantee relationships also helped diminish the power imbalance between the foundation and the grantee.

He and Cisco moved away from early ideas about having strict guidelines for applicants and internal grantmaking formulas. Instead, they sought to minimize paperwork and agreed to accept rolling applications and distribute grants in two annual cycles. Potential grantees would submit a letter of inquiry. If the foundation was interested, Ellsworth would schedule a visit that would enable him to develop relationships with grantees framed around shared goals and objectives. The LBF did not fixate on formal evaluation, reporting, or metrics, investing little time in documentation beyond what was required by law. Instead, Ellsworth took a personal approach based on his ability to monitor progress in regular dialogue with grantees. Much of what the LBF hoped to achieve involved long-term cultural shifts that were not easily captured by numbers or percentages. So, together with grantees, the LBF measured progress against process-oriented benchmarks outlined in grant agreements.

Evolving relationships with grantees enabled Ellsworth to develop a “telescoping focus” strategy for grantmaking in a spend-down situation. With each grant he learned more about a field and a grantee’s capacity. He also learned about their needs and dreams. If a grantee had the capacity and the vision, more focused grants would follow. Eventually, Ellsworth expected the list of grantees to narrow. All of this effort aimed to identify a handful of grantees and projects that would ultimately receive the foundation’s major dispositive gifts as the foundation spent itself out of existence.

Throughout the first three years after adopting the foundation’s three program areas, Ellsworth and Cisco maintained some flexibility to make non-core grants as necessary, at least in the short run. Funders, after all, are always under social pressure from colleagues and friends, as well as the community-at-large. Sometimes, funders need to make a grant to preserve goodwill. Other times, circumstances create unexpected needs. In 2003, for example, severe wildfires ravaged San Diego, and the LBF donated $100,000 to a $2 million drive by The San Diego Foundation’s Wildfire Fund, along with $50,000 each to the local Red Cross and the food bank. The LBF continued to make grants like these over the next several years, but they diminished over time as the foundation steadily focused its giving into the three strategic areas.

Key Insights:

Relationship-based grantmaking is an art. Strategic partnerships between grantees and funders can help both achieve long-term goals and greater impact. The Legler Benbough Foundation believed that successful grantor-grantee relationships are anchored in dialogue and trust earned over time. Shared goals and accountability play a key role in keeping funders and grantees on the same page and building trust. The funder is constantly trying to balance efforts to catalyze change with resources and interaction, while being careful to listen and avoid forcing an agenda on the grantee. In a spend-down situation, these relationships play a key role in the creative development of dispositive grants.

Study Questions:

What are the strengths and weaknesses for the funder and the grantee in a relationship-based approach to grantmaking?

What skills or talents does a funder need to successfully pursue a relationship-based approach to grantmaking?

How can funders leverage the experience and expertise of grantees to develop grantmaking programs?

Does the inherent power imbalance between the grantor and the grantee undermine efforts to achieve shared goals? If so, how should this power imbalance be addressed?

Early on, the LBF made small experimental grants to test ideas and gauge the capacity of grantee organizations. How can this strategy help a foundation narrow its focus while strengthening grantees?

Restructuring the Board

With a strategy for grantmaking in place by 2005, Ellsworth and Cisco were ready to expand the LBF board to bring in others who could provide insight and advice, as well as an added layer of accountability to their work. They sought leaders with executive experience and a capacity for financial stewardship, a strong track record in at least one of the foundation’s focus areas, and a long pattern of substantial community involvement. These attributes would lend credibility to the foundation’s work. In addition, to reduce the potential for board conflict, which would create real difficulty in a spend-down situation, they sought directors who knew each other and had a history of working together. They also wanted people who were late enough in their life or career to stave off the temptation to extend the foundation’s spend down.

Early in this process, Ellsworth had lunch with a fellow attorney named Pat Crowell, whom he knew from Rotary and other civic organizations. Crowell and his wife were very involved in the nonprofit sector. Pat had served on the board of the Timken Museum in Balboa Park for years. During their conversation, Ellsworth explained that the LBF was looking to add three new board members. To Ellsworth’s surprise, Crowell said he would be happy to serve, but he did not want to be involved in deciding individual grants. He had served on the board of a grantmaking organization and observed that board members were often ill-informed about grantees and discounted the advice of staff or community members, which made no sense to him. Additionally, since he sat on several nonprofit boards, he feared that, if affiliated with a funder, he would be hounded for grants.

This conversation pushed Ellsworth to think creatively. In the spring of 2005, Ellsworth revised the LBF’s bylaws to create two kinds of directors. He and Cisco would be “Operating Directors,” empowered to continue making grant decisions and conduct the day-to-day business of the foundation. Meanwhile, a second category of “Governing Directors” would exercise financial oversight, review compensation, and be responsible for the foundation’s long-term vision and grantmaking policy. After having an external consulting firm review and approve this plan, Ellsworth and Cisco formally adopted the changes in June 2005 and then promptly elected a new board of directors.

Pat Crowell was joined as a governing director by Hugh C. Carter, an engineer with connections to the innovation sector and tech researchers at UC San Diego, and John G. Rebelo, a successful banker and leader in the city’s Portuguese community who had extensive experience with nonprofit board service. These new board members reflected the criteria that Ellsworth and Cisco had developed, but they were also all white males of comfortable means. They represented a social network that was centered around the downtown business community, the Point Loma neighborhood, and the Yacht Club. Every one of them was a Rotarian, “which is where the leaders of San Diego were,” Rebelo says. Ellsworth defended himself by saying that having board members who understood one another and had worked together enabled the board to make decisions quickly. This was a major reason that he and Cisco had chosen to keep the board small. Given the foundation’s limited life, getting things done was his top priority.

From his work in the Diamond and in discussions with other grantmakers, Ellsworth was aware of the debate within the nonprofit world over the power imbalance between donors, who had the money, and grantees, who needed the money, as well as the idea that grantees should be included on foundation boards. “The main problem with the ‘power dynamic,’” Ellsworth said, “is created by the reinforcing attitude of that dynamic reflected in the process and action of the foundation. Your parents have a power dynamic yet one that you know was of immeasurable help.” He suggested there were better ways to address this power imbalance than by putting grantees on the board. He believed that the LBF’s relationship-based approach to grantmaking, which focused on listening to and respecting the grantee over the course of conversations with Ellsworth, as the foundation’s chief program officer, and in face-to-face conversations with the foundation’s board, was a more constructive way to resolve the power imbalance question. The LBF also regularly invited grantees to sit with the board to discuss the foundation’s broader grantmaking strategy, an approach that valued their time and expertise. “Asking them to sit on the board,” he said, “would make them have to sit through other discussions that would be of little interest to them.” He asserted that questions of bias and diversity should be measured by policies and grantmaking processes rather than what he took to be arbitrary rules of inclusion “that do not address the underlying issues.”

The LBF’s Board Criteria

-

Possess substantial executive or financial experience to ensure that the board could execute its fiduciary responsibilities.

-

Demonstrate a long track record of community involvement.

-

Expertise or experience in at least one grantmaking area.

-

Be of an age or career stage that would make it unlikely that the candidate would seek to significantly extend the foundation’s life.

-

Have a personal, trusting relationship with existing board members.

Fundamentally, Ellsworth and Cisco’s instincts when it came to board recruitment reflected the continuing nature of philanthropy in the United States as a private activity conducted primarily by people who are often related by blood or friendship and want to promote a shared idea of the public good. It also underscored the continuing importance of personal networks to the business of getting things done in a community. In many ways, given their age, their class, and their social backgrounds, one would expect that these men would be inherently conservative in their approach to changes in society. In reality, they were veteran risk-takers and had the ability and willingness to be creative in their approach.

Key Insights:

Strategy demands focus. Emergencies and unforeseen opportunities will always test the strategy. And from time to time, to be a good citizen or to recognize the historic priorities of the donor, foundations will have to make non-strategic grants. Greater impact, however, comes from greater focus. In the Benbough model, the foundation avoided mission creep and the proliferation of “pet projects” by waiting to expand the board of directors until after the foundation had defined its strategy. Board members with similar backgrounds were chosen to make decision-making more efficient and avoid the temptation to alter the strategy or postpone the spend down. The risk in this strategy is that board members will not see or understand other perspectives or miss opportunities for greater impact. This risk can be mitigated by including grantees in policymaking discussions.

Study Questions:

How does the LBF’s board structure and governance model differ from most other private foundations in the United States?

Under what circumstances does it make sense to have board members also serve as the primary administrators of a private foundation?

Foundation board members often advocate for grantees they know and support. What challenges or opportunities does this tendency pose for grantmaking?

What challenges and opportunities are presented by leveraging board members’ experience, expertise, and social networks to develop grantmaking programs?

Maximizing Impact

With the formal revision of its bylaws and reorganization of the board of directors in 2005, the LBF moved closer to being a prescriptive foundation with a defined focus, clear objectives, and a group of community partners and grantees with whom it pursued its work. At the new board’s first meeting in August 2005, Ellsworth discussed the foundation’s grantmaking philosophy. In all three arenas, he noted, the foundation frequently worked to leverage the impact of its grantmaking by filling in gaps or seizing opportunities in an environment where funders with greater capacity were already working. The foundation also sought to use its resources to promote institutional collaboration to realize synergies and economies of scale. Finally, in addition to “focus and objectives,” the foundation believed that “a personal, sustainable relationship with the grantee is necessary” for success. Until this relationship develops, Ellsworth said, “the power dynamic of grantor-grantee prevents the kind of cooperative thinking and dreaming that forms the basis for creative grants to address shared objectives.” Moreover, Ellsworth asserted, unless the foundation developed this relationship of trust and working together, it would not learn what it needed to know to be able to have the greatest impact possible.

Building on his relationship-based approach to grantmaking, Ellsworth continued to work with potential grantees, other funders, and government and civic leaders to fulfill immediate needs and support solutions that promised long-term returns to the community. He adjusted in the moment when, for example, he saw grantees fall into “mission creep” resulting from their efforts to sustain funding by agreeing to things funders wanted to see, regardless of their efficacy. He avoided these scenarios by encouraging candor and remaining open to partners’ needs.

The new board structure and grants process proved critical to achieving impact. The governing board held quarterly, day-long meetings, each of which was focused on one of the LBF’s three grantmaking areas. Devoting this level of time and attention allowed the board to develop expertise in each area. It further enabled them to evaluate the potential impact that LBF grantmaking could have in each sector, then establish sound policies that reflected the board’s deep expertise in each grantmaking area.

The board’s process also enabled Ellsworth to create the kind of personal relationships with grantees that proved essential to the foundation’s success. By meeting with grantees in grant policy discussions, the board demonstrated its respect for the knowledge and work of its grantees. By empowering Ellsworth to work with grantees and make grant decisions on the spot and without a cumbersome approvals process, the board helped create an environment of trust in which the grantee was a partner in the decision making as well as project proposals. This was an intentional correction on the part of the LBF. In various meetings over the years, Ellsworth had grown frustrated by what he saw as a byzantine decision making process in other foundations. Long, complicated approval processes not only resulted in missed opportunities; they often left a negative impression in the minds of grantees. Rather than the trust-based approach the LBF believed in, other foundations seemed to inadvertently diminish their grantees’ faith and confidence in the funder. When it came to working with grantees, Ellsworth concluded that “the creativity, spontaneity, and momentum of positive discussions with the grantee needs to be backed up with the authority to make decisions on the spot and be flexible to the current situation.” Being able to make quick grants decisions also allowed the LBF to eliminate costly paperwork, leaving more time and resources for the actual, charitable work of the foundation.

The board knew Ellsworth vetted potential grantees through research, his extensive network, and his own ability to evaluate plans, assess their potential for success, and gauge the long-term sustainability of grantee programs. The board also appreciated his efforts to identify the best leadership in grantee organizations and his constant efforts to observe how well the boards of grantee organizations could communicate vision, establish realistic and clear goals, and meet them. Ellsworth reported back to the LBF board on all grants, including the vision, process, and potential of each grantee. He solicited unvarnished feedback from the board. During their meetings, the LBF board had vigorous, analytical discussions about what was working and what still needed to be done to achieve the desired impact. Ultimately, however, the board entrusted Ellsworth and Cisco to manage day-to-day operations, including important investment and grants decisions, that allowed them to create effective grantee relationships and to act creatively and flexibly so the foundation could work with grantees to to achieve the objectives and the impact it desired.

Key Insights:

Forming a board with people who know one another and adopting a relationship-based strategy for grantmaking minimizes administrative costs and encourages greater candor and creativity. When circumstances change or things don’t go as planned, the grantor and grantee can quickly adjust. Empowering a single representative of the foundation to make grants on the spot can affirm a foundation’s ability to follow through on its commitments and helps build trust with grantees.

Study Questions:

How can spend-down foundations—which are by definition short-term entities—help grantees develop and work towards long-term goals?

How are dialogue and trust assets in the grantmaking process? What are the risks in a relationship-based approach to grantmaking?

The LBF empowered a single individual to make grants on the spot. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this approach for grantors and grantees?

How can a smaller foundation use its resources to fill gaps or seize opportunities in environments where larger funders are already working?

The LBF generally relied on mutually agreed upon goals and dialogue to assess the impact of its grantmaking. What are the strengths and weaknesses of this approach?

Evolving a Plan for Sunset

Because the LBF gave at around 5 percent in a booming economy and had made no disbursements from its corpus, the foundation’s assets continued to grow. By 2006, they were nearly $46.6 million. Observing that Ellsworth and Cisco were both in their seventies, and that the LBF’s work depended on them, the governing directors asked both men to share how long they intended to keep working. They also requested plans in case either man became incapacitated.

The operating directors had anticipated these questions. In fact, they had been discussing a target date for the spend down since 2003. But Ellsworth did not want to become so preoccupied with the spend down that the foundation lost sight of the important developmental work it was doing with grantees or cut short the process of identifying dispositive grants that would have significant impact.

The board agreed to wait but the issue continued to be on the table. Tom Cisco reduced his workload in the face of some health issues in 2006. A contracted bookkeeper and investments manager picked up the slack. Discussion continued on both the issue of potential disability of Ellsworth and Cisco as well as the plan for eventual spend down. Regarding the disability issue, Ellsworth proposed that if he and Cisco could not serve, the LBF’s assets would be transferred to The San Diego Foundation with their staff distributing foundation assets pursuant to the LBF’s strategy.

On the face of it, the directors saw this contingency plan as a viable option, but they also had a concern whether The San Diego Foundation would follow their wishes and their strategy. The LBF articulated this concern to Bob Kelly, the head of The San Diego Foundation. Kelly reassured the board, citing the foundation’s long history of honoring donors’ wishes. He also explained that his organization had adequate staff to ensure an effective and prudent spend-down process. Kelly’s institutional authority and history with Ellsworth reassured the LBF board. Ellsworth and Kelly then developed plans for The San Diego Foundation to handle the LBF’s assets pursuant to a standby agreement. The pair also agreed that the LBF would update The San Diego Foundation on the LBF’s thinking on prospective grantees every year and share this information with key staff at The San Diego Foundation.

Although the LBF had not adopted a formal spend-down plan, Ellsworth and Cisco developed proposed criteria for the dispositive gifts the foundation would make as part of the spend down. These criteria stressed the continuity between the foundation’s current grantmaking, with its emphasis on close relationships with grantees in the three program areas. Pat Crowell noted that collaboration had been a core principle of the foundation’s grantmaking, and it should be continued with the dispositive grants. Knowing that some of the dispositive gifts might be large and understanding that some of the foundation’s grantees were relatively small organizations with limited capacity, he also expressed concern that management issues might have to be considered when making these final grants.

Committed to the management principle of “focus,” Ellsworth cautioned the board about the importance of retaining that focus in spite of the “avalanche of opportunity” that would undoubtedly be presented to the LBF as soon as definite plans for final spend down were announced. He also reminded the board that while it was important to continue to communicate the LBF’s intention to spend down eventually, in light of the uncertain time for the completion of projects currently being funded, it was impossible to predict the specific time for that spend down. Therefore, the foundation needed to exercise caution in suggesting any specific spend down date.

As the foundation continued its spend-down discussions, Ellsworth emphasized the importance of a continued commitment to the three established focus areas, as well as the grantmaking process by which he exercised grantmaking authority while the board focused on grant policy. Because they trusted his integrity and judgement, the board supported this approach, particularly because they did not want to become targets for nonprofits lobbying for grants once the formal spend down process was announced.

In the years that followed, the LBF continued to narrow its focus within each of its grantmaking areas and reported these changes to The San Diego Foundation. This ensured that, in the event that Ellsworth and Cisco were unable to complete the sunset, the executors of the dispositive plan could confidently spend down the foundation’s assets in a way that reflected the objectives of the founder and the operating directors, as well as the foundation’s most recent thinking and priorities born of the relationship-based strategy.

Key Insights:

The Legler Benbough Foundation’s model was heavily dependent on two key individuals and a strategy for spend down. Recognizing the risks in this approach, the board’s contingency plan relied on the local community foundation to ensure continuity. The LBF’s lead grantmaker communicated regularly with the president of the community foundation about the strategy for dispositive grants. In the meantime, the LBF worked to ensure that the time pressures of a spend down, in combination with unforeseen changes in circumstances, did not lead to grantmaking outside of the foundation’s strategic focus.

Study Questions:

From the time of the donor’s death, the LBF saw itself as a spend down. What was its strategy for developing dispositive grants?

Should the criteria for dispositive grants be different from any other grants?

If a foundation relies on one individual to oversee grantmaking, what options should it consider for contingency planning if that individual becomes incapacitated?

How does a spend-down approach to grantmaking better position a funder to respond to grantee needs during an economic crisis?

Challenges of the Great Recession

When the Great Recession destabilized the global economy, assets collapsed for foundations everywhere. The LBF saw the value of its corpus decline by 31 percent from December 31, 2007 to December 31, 2008. This financial shock occurred just as Ellsworth was formalizing his first memo on the LBF’s sunset plans. It pushed the foundation to question its sunsetting strategy. Facing a historic crisis, should the foundation curtail its giving in line with the loss of its asset value and ride out the recession? Or, should it re-focus its grantmaking to meet urgent needs brought on by the crisis?

Prior to 2009, the foundation’s grantmaking had totaled about $1.5 to $2.0 million a year. With the decline in its assets, the LBF was only required to give about $1.0 million that year. A perpetual organization might have chosen to limit its grantmaking to avoid dipping into corpus. As a spend-down foundation, however, the LBF believed there was no reason to turn its back on grantees to sustain the foundation’s financial position. After meeting with grantees to see how the recession was impacting them, the LBF chose to continue its grantmaking at pre-recession levels. It also decided to emphasize giving in the Diamond Neighborhoods and Balboa Park where people and institutions faced the greatest need. Nevertheless, with the foundation’s sunset on the horizon, the LBF continued to narrow the focus. In 2010, the board agreed not to fund new grantees unless there was an exceptional need and a clear connection to existing work.

Key Insights:

In times of economic crisis, spend-down foundations, who don’t need to worry about preserving their corpus, can maintain or accelerate their grantmaking to help grantees compensate for a general reduction in resources. With a relationship-based approach to grantmaking, a foundation like the LBF may choose to prioritize those grantees who show the most promise in terms of their capacity and vision and alignment with the foundation’s strategy. Supporting grantees during these difficult times strengthens the bonds of the relationship.

Study Questions:

What parts of the LBF’s governance model seem the most helpful when it came to addressing grantees’ needs during and after the Great Recession?

How can funders plan for unexpected economic crises? How should these crises affect their grantmaking?

How should a relationship-based approach to grantmaking affect a foundation’s financial management?

Gearing Up for Spending Down

Peter Ellsworth had expected that a slow, deliberate process would reveal a clear plan for spending the LBF out of existence. But instability with the stock market, uncertainties with grantee organizations and their projects, and challenges with partners made efforts to formalize the spend down more difficult than anyone had anticipated.

Financial and human factors within the foundation also took their toll. In 2011, for example, market fluctuations stripped away $1 million in assets, and the board had to focus on reevaluating its investment advisors and reducing its grantmaking for the next year. Then, in November 2011, director Hugh Carter passed away. He was replaced by Frank Arrington—a mortgage banker and pillar of San Diego’s nonprofit community. Frank unexpectedly died two years later. The board had to decide whether it made sense to elect a successor. One potential board member, however, was a perfect fit.

After Bob Kelly announced his intention to retire from The San Diego Foundation in September 2014, he was elected to the LBF board. Given his knowledge of philanthropy and nonprofits in San Diego, his close relationships with Ellsworth and the other directors, and the LBF’s contingency plan to transfer its assets to The San Diego Foundation in the event that Ellsworth was not able to oversee the final spend down, Kelly’s election made perfect sense.

Planning for the spend down was expedited in early 2013, when Tom Cisco announced that he was preparing to resign for health reasons. Ellsworth and the board contracted out for check- payment and investment services with Goldman Sachs and in 2015 began the process of moving the remaining $31 million of the LBF’s assets from investments to fixed income, so the foundation could be confident in its spend-down budget.

LBF Governing Directors, 2005-2021.

Pat Crowell, Hugh Carter, John Rebelo, Frank Arrington, and Bob Kelly.

As the foundation moved closer to its sunset, Ellsworth continued his telescoping grantmaking strategy. Ellsworth understood that spend down deadlines could generate a healthy kind of pressure. Giving from the corpus would strengthen grantee organizations while holding the foundation accountable to the donor’s wishes. It would also force the board to refine its criteria for dispositive grants, think hard about which partnerships were working, and empower partners to hone their plans to ensure they were sustainable after the LBF’s departure. However, because of grant project delays and uncertainties, the LBF could not establish a firm timeline.

In 2014, the LBF told all its current grantees that it intended to spend down within “a few years.” Although the foundation had made clear its intent to distribute all of its assets from the beginning, many grantees had not paid attention. This announcement caused some anxiety. Ellsworth worked to reassure grantees and manage expectations about the LBF’s dispositive plans.

Uncertainty, however, continued to impede Ellsworth’s efforts to finalize the foundation’s plans. Specifically, a major project that would have revamped the traffic flow and parking situation in Balboa Park, dragged on due to a series of legal challenges from special interest groups. Where the LBF had hoped to complete its grantmaking over the course of 2015 and 2016, that project kept the foundation open. When it became clear in early 2019 that the project in Balboa Park would not move forward, the LBF created a final budget and mapped out its dispositive giving to various grantees in different parts of its core grantmaking areas and terminated the standby agreement with The San Diego Foundation.

Throughout the spend-down process, the LBF was concerned about the adverse effect on grantees when LBF stopped supporting them and the work that was needed to ensure the sustainability of those grantees. They were also concerned that some smaller grantees would be better off if they received multiple, smaller payments rather than a single lump sum. The directors, however, did not want these concerns to delay the final dissolution of the foundation. To solve this problem, The San Diego Foundation agreed to create a non-endowed donor-advised fund, with the LBF board members as advisees. This arrangement allowed for final payment on some dispositive grants through 2021. The LBF then submitted the necessary forms and commenced its final spend down.

Key Insights:

The LBF’s telescoping focus strategy depended initially on an open-ended approach to spend down. The foundation needed enough time to build relationships with grantees, develop a shared vision, test ideas and projects, and draft plans for major dispositive grants. With this approach, some grantees became somewhat dependent on the foundation, lost sight of the spend down, and were surprised when the LBF announced a target date. The foundation also had various issues to work through related to dispositive grants, including how to complete pending projects and how to ensure that grantees would remain sustainable after the dissolution of the foundation. Time-tested relationships, however, allowed the foundation and grantees to work through these issues and execute their plans successfully.

Study Questions:

How should funders strike a balance between incentivizing action and supporting the natural direction of grantees?

How should a spend-down foundation develop and communicate its plans for dissolution?

To what extent should the long-term solvency of a grantee organization shape a spend-down foundation’s grantmaking decisions?

The LBF elected not to specify a spend-down date. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this approach?

Additional Insights - Case Study Sidebars

Lessons Learned

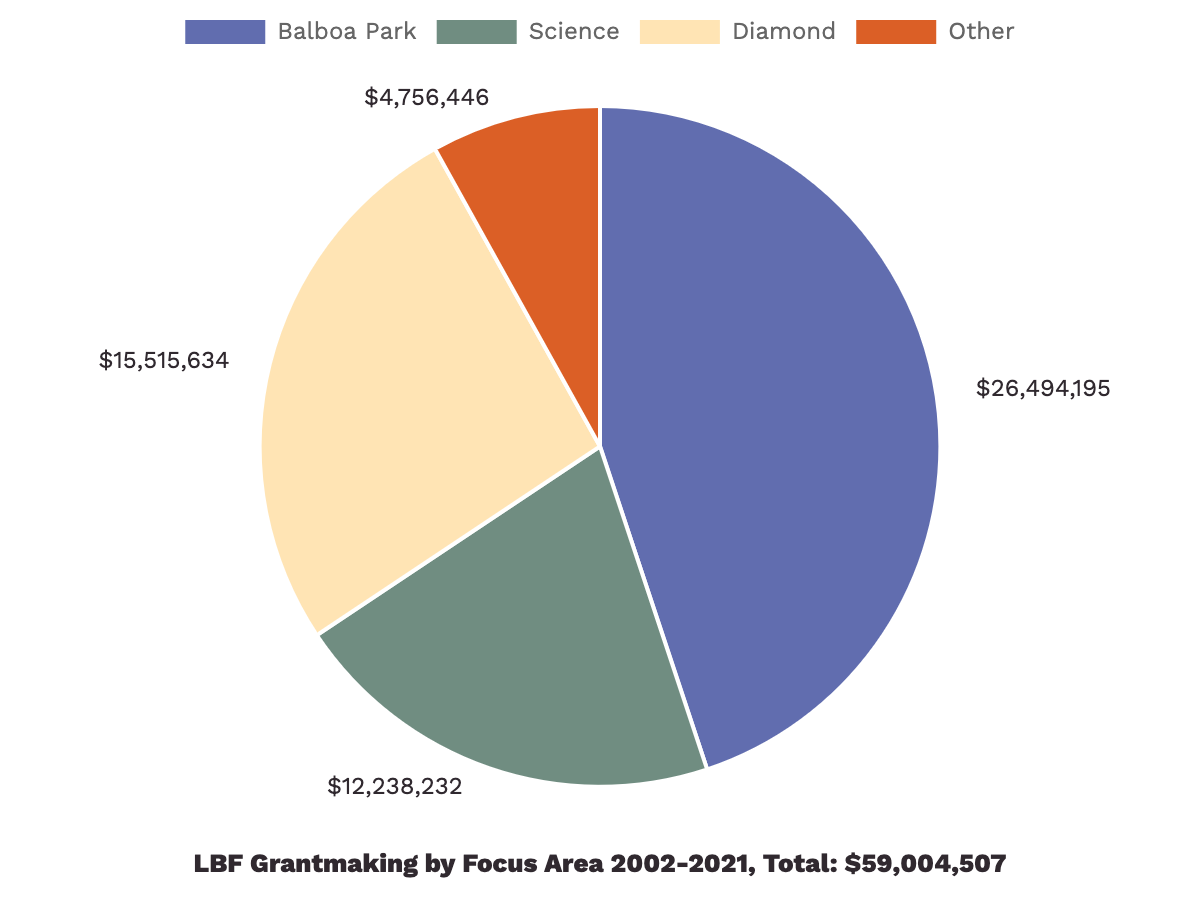

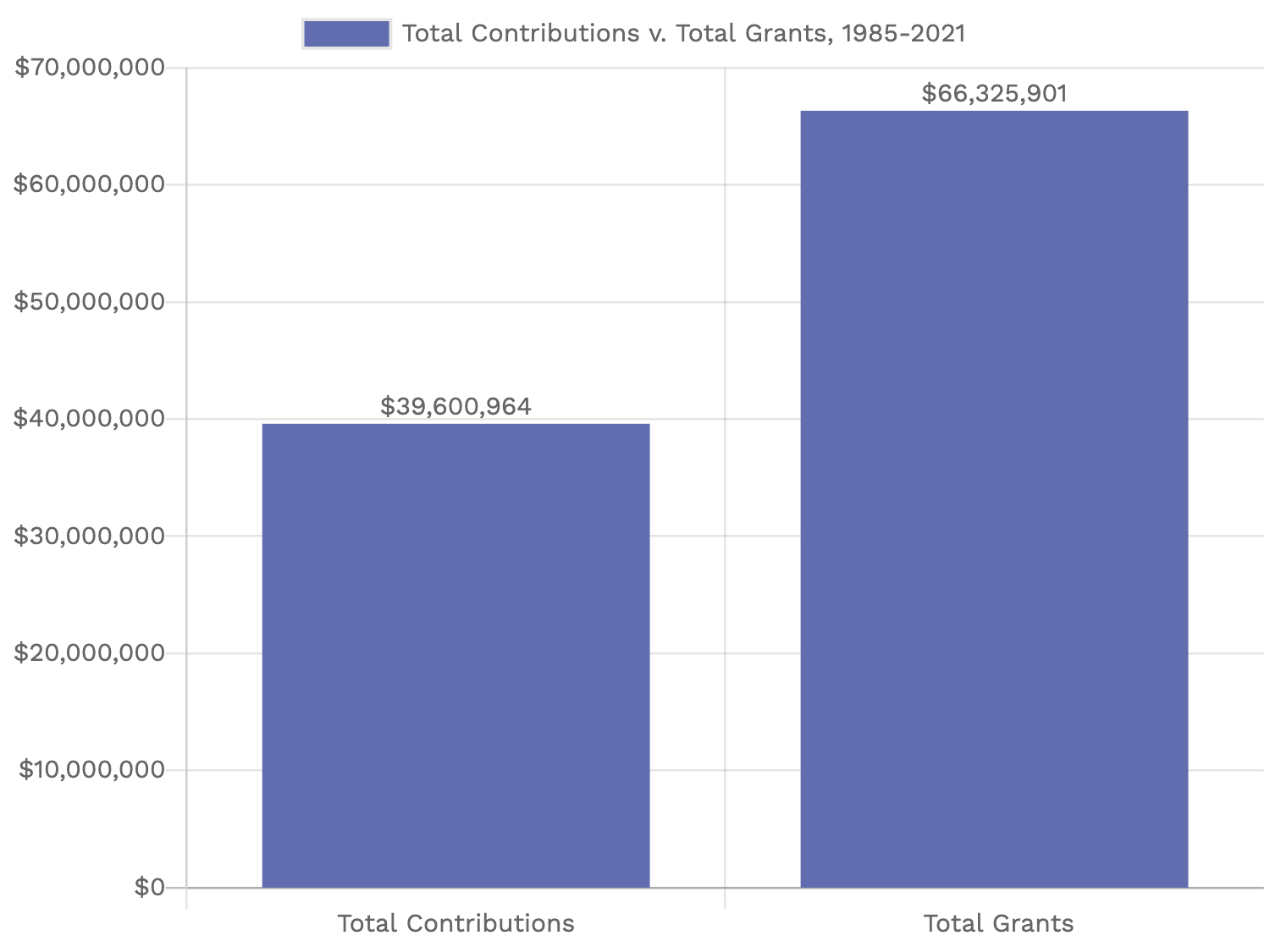

Focus: Establishing three specific grantmaking areas and continually narrowing the focus within them to identify grantee initiatives that could make a major impact and accomplish something significant was the key to the LBF’s success. Following this strategy, the foundation was able to devote the necessary time with grantees to build effective relationships in each area. Having a narrow focus also reduced the number of grant requests and the need for a new process with each grant, thereby eliminating considerable administrative costs in terms of both time and money. This strategy enabled the LBF to limit its administrative expenses to a level well below that of peer foundations. This ultimately empowered the foundation to give more to its grantees than it otherwise could have afforded. Indeed, in the two decades following its reorganization, the foundation gave $59,004,507 in grants from an asset base that totaled $41,595,501 as of 2002—even after the LBF suffered a 31 percent loss to its asset value during the Great Recession.

Directors: Establishing narrow focus areas allowed the LBF to recruit directors who had longstanding interest and expertise in at least one of the foundation’s grantmaking arenas. This provided an essential source of knowledge and crucial networking opportunities that formed the basis of the foundation’s grants policy. The LBF intentionally formed a board made up of members who had worked together and knew each other. This minimized the potential for conflict and reduced the amount of time it took to develop trust. It also encouraged open and candid board discussions. As a spend down, the LBF intentionally sought to appoint directors who could serve for the duration of the foundation’s life, thereby eliminating internal politics and power struggles. Rather than focusing on these issues, the board focused its energy on making grants to organizations that they cared about. Because the board was not tasked with making decisions about day-to-day operations or grant approvals, they could devote their attention to long term outcomes, investment returns, and the success of the foundation. In short, the LBF’s governance strategy effectively and efficiently utilized the time and talent of its board members.

Process: Giving the individual that works most directly with grantees the authority to make grant decisions on the spot maximized the foundation’s ability to build trusting, open relationships with grantees. Involving them in the decision making process led to frank, ongoing conversations that produced creative new project ideas that likely would not have occurred had the foundation pursued a traditional grants model. A foundation’s grantmaking process reflects its philosophy, and the LBF’s process eliminated the perception that every new grant should be evaluated as a completely new endeavor. Instead, both the foundation and the grantee could rely upon ongoing discussions and interactions in a way that reinforced the notion that the work they shared was about helping the grantee, not rewarding the foundation. This approach reduced the kind of power dynamic between funders and grantees that sometimes leads to misunderstandings and lost opportunities.

Spend Down: The spend-down model offered the flexibility that the LBF needed to address grantee needs in creative and effective ways. By eliminating the 5 percent requirement and not limiting grantmaking to levels that would be consistent with ensuring the perpetual existence of the foundation, the LBF was free to spend money when and how it needed to support the needs of grantee organizations and initiatives. By focusing on grantmaking rather than maintaining the name of the foundation forever, the LBF found it could communicate to grantees that “it is not about me.” In the end, the LBF’s express efforts to minimize public recognition for its grantmaking made it easier to get things done.

Personal Perspective:

Peter Ellsworth

It was only when Legler started talking about having a real impact that I began to be intrigued.Peter Ellsworth, president and operating director of the LBF

“Legler was very clever. We tried to pin him down on what he wanted us to do with the money. He wouldn’t say, but he was very clear that he wanted to have an impact and accomplish something significant. He was also convinced that a spend-down model, completed during our lives, was essential to prevent mission creep in successive generations.

In retrospect, it is clear to me that Legler was vague about the specific use of his funds for a reason. He knew Tom and I very well and knew that we were not looking for a job and that we would not be interested in pursuing this unless it was a foundation that would have impact and unless we had the authority to create a model we believed in to distribute the money within the context of his expressed wishes.

In retrospect, it is clear to me that Legler was vague about the specific use of his funds for a reason. He knew Tom and I very well and knew that we were not looking for a job and that we would not be interested in pursuing this unless it was a foundation that would have impact and unless we had the authority to create a model we believed in to distribute the money within the context of his expressed wishes.

Legler had worked with Tom and with me for decades. He knew that I hated all the stuff related to accounting and investment, whereas Tom was very good at it. And he knew that Tom didn’t really want to be involved with the details of grantmaking. So he suspected that we would be a good team. He turned out to be right.

Over lunch one day, Tom asked me, ‘How many employees did you have when you were CEO of Sharp Health Care?’

‘About 10,000,’ I responded.

‘I had about 70 at the bank,” he said.

After a few moments, I asked, ‘what’s your point?’

Tom looked at me and said, ‘Let’s never have an employee.’

And we never did. Instead, we allocated responsibilities between us, leaving me with grantmaking and Tom with the administration. We were a perfect fit.

Tom and I worked together on everything and, after many years, could almost always finish each other’s sentences. When it came to developing a grants strategy and organizing our governance model, we talked to others and worked closely to create objectives and grantmaking areas that the LBF would pursue.

From long executive experience, we both understood the importance of honoring and respecting the work of those on the ground. This naturally led to the development of a grantmaking strategy based upon listening to, working with, and learning from those we wished to serve. Although this played out differently across each of our three focus areas, the principal was the same.

Working directly with grantees and taking on innovative projects with them is not ‘feel good philanthropy.’ It is difficult work and while you have great pride in accomplishment, you also feel it personally when you suffer defeats. When a collaboration you worked on takes a different path, it is a personal loss and you feel it emotionally. And, sometimes, you get blamed for your role. This is especially true when you make promises to a community based on agreements with partners. If the partners change course and you are forced to break your promise to the community, it hurts and erodes trust. Yet the opportunity to work with amazing, creative, dedicated people in all of these focus areas made it all a wonderful experience.

Both Tom and I were very fortunate to have the support, confidence, expertise, and trust of the governing directors. Their process, trust in us, and encouragement and participation in the face of failure as well as success was a critical factor in everything we achieved.

For all these relationships and the inspiration they provided, I will be eternally grateful.”

Personal Perspective:

Bob Kelly

The story of the Legler Benbough Foundation offers a great example of what people can do when they develop trust. When the underlying agreement is really anchored in a handshake, a lot of things are possible.Bob Kelly, governing director of the LBF and former CEO of The San Diego Foundation

“Pete Ellsworth and I have known each other and worked together for a long time, although we come from very different backgrounds. I grew up in the housing projects in Boston in the 1950s. We lived in a three-bedroom apartment with five kids and my parents. My parents also took in another girl because of her home life. That was the way it was. People took care of each other with whatever they had.

I came to San Diego because of my brother. He joined the Navy and became a Marine corpsman. He served in Vietnam and then was stationed here. In 1967, after I graduated from high school, he convinced me to move here and go to school. We shared a rented house in Point Loma with five other guys who were all Marine Navy corpsmen. To pay the rent, I worked in a gas station. Washing windshields and checking oil, I ended up meeting many of the leaders in the community.

I got my first job in the nonprofit world with the American Cancer Society and eventually became CEO for all of Southern California. After Pete became CEO of Sharp Health Care, a mutual friend arranged for us to have breakfast. To my surprise, Pete offered me a job. For five years I worked closely with him as he was building Sharp into the largest healthcare organization in San Diego County.

Pete is a bulldog. He is brilliant. He is focused. He knows exactly what he wants to get done. As a CEO, he did not suffer fools. He did ask people’s opinions. As staff, we would argue with him and all of this good stuff, but he was the final decision-maker. Some people don’t like that, but a lot of people do.

I knew he had told the board he was leaving after ten years. Before that time, I agreed to become CEO of The San Diego Foundation. After Pete retired and Legler Benbough died, we began to talk frequently about philanthropy and nonprofits, especially in Balboa Park. Pete was really pushing the museums to work together. When they came to me with a plan to create a consortium, I suggested they talk to Pete.

Tom Cisco and Pete knew Legler Benbough. They understood that he wanted his money to make a difference. They relied on the board for insight and advice. As the foundation approached its spend down, Pete and I talked regularly about what he was thinking for the final dispositive gifts in the event that something happened to him and we had to take over. Given these conversations, it was pretty natural, after I retired, for me to join the Legler Benbough Foundation’s board.

All of us on the board have known one another for a long time. Pete and I don’t always see eye-to-eye. But we respect and understand each other. We are both committed to getting things done, avoiding the administrative waste-of-time stuff. The story of the Legler Benbough Foundation offers a great example of what people can do when they develop trust. When the underlying agreement is really anchored in a handshake, a lot of things are possible.”

Sources & Bibliography