The LBF and the Diamond Neighborhoods:

Building personal relationships with residents of a disadvantaged community to learn from them and work with them to develop community-driven solutions and organizations to address critical issues.

How can philanthropy empower disadvantaged communities?

The LBF Governance Model After 2005

Operating Directors. The donor recruits directors that s/he knows and trusts to perform day-to-day administration, establish grant focus, make grants, and to act as operating directors.

Governing Directors. The operating directors recruit a small board of governing directors who have knowledge and expertise in the foundation’s primary grant areas and are familiar with one another. They provide administrative oversight to operations, set compensation, and offer insight to the grants policy and the foundation’s vision.

Spend Down. Establish a spend-down strategy and timeline to distribute the foundation’s assets during the operating directors’ lifetimes. Dissolve the foundation after making dispositive grants in each focus area.

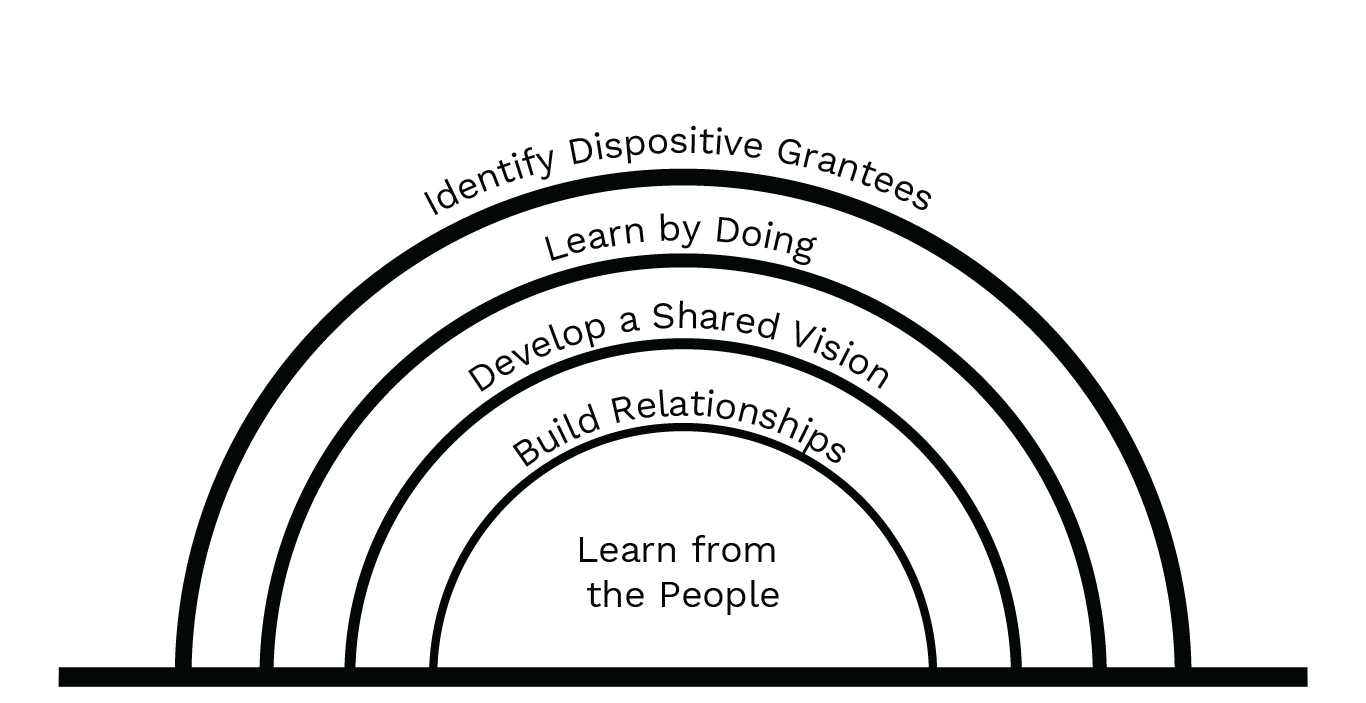

The LBF Grantmaking Model After 2002

Focus and Relationships. Define specific focus areas and establish personal relationships with potential grantees working in each area. Use initial grants to determine the capacity and vision of grantee organizations.

Grantees as Partners. Listen to and learn from grantees. Recognize that the people working in context have the best ideas for addressing the issues in their field.

Collaboration. Work with grantees to refine their ideas and maximize impact. Treat all grantees with respect and admiration for their achievements. Grants recognize the work of the grantees, not the foundation.

Narrow the Focus. Work with grantees to narrow the grants focus over time. Use this process to identify grantees with the strongest records and greatest potential for making significant impact.

Dispositive Grants. Work with these partner grantees to make dispositive grants that will achieve the maximum impact with the resources available. Through this process, spend-down the assets and dissolve the foundation.

This document includes the case study and some, but not all, of the sidebars published on Benboughlegacy.org. Sidebars referenced in this printed document can be found at the end of the main narrative in a section titled Additional Insights - Case Study Sidebars.

About the Legler Benbough Foundation

The Legler Benbough Foundation (LBF) was a private philanthropic foundation located in San Diego, California, that operated from 1985 to 2021. During that time, the foundation gave some $66.3 million to organizations throughout the San Diego community. Endowed by a lifelong San Diegan and proprietor of his family’s mortuary business, George Legler Benbough (who went by “Legler”), the LBF funded charitable initiatives of personal interest to the donor from 1985 until his death in 1998. At that time, and at Benbough’s request, two of Benbough’s professional confidants, Peter Ellsworth and Thomas Cisco, assumed control of the foundation. They devised a focused strategy to spend down the foundation’s assets to “accomplish something significant” in San Diego before the end of their working lives and in 2005 recruited a board of governing directors to guide this process.

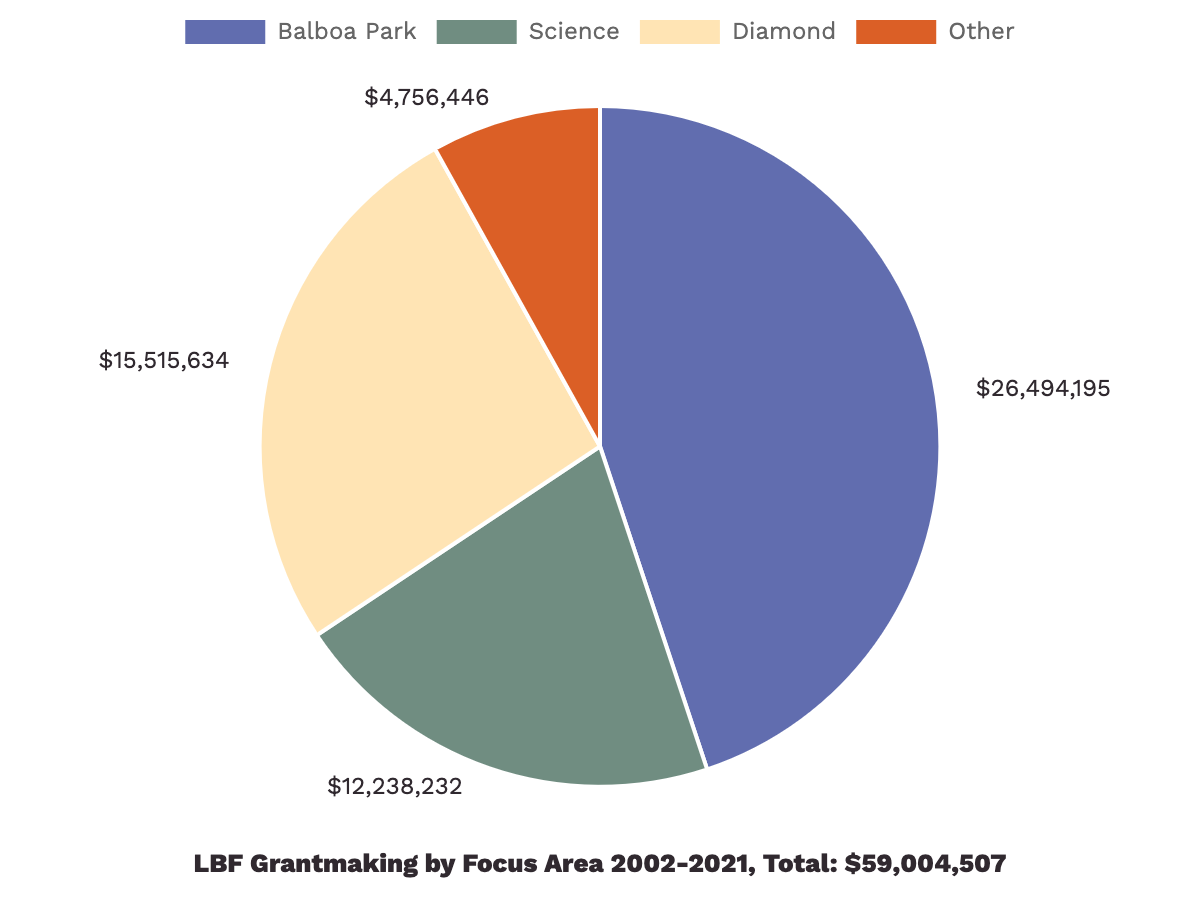

After 2002, the LBF focused on improving the quality of life in San Diego in three core arenas: fighting systemic disadvantage in the Diamond Neighborhoods in southeast San Diego, supporting arts and cultural institutions in Balboa Park, and promoting research and technology development within San Diego’s burgeoning innovation sector as a way to fuel economic development. Given the goal to spend down the foundation’s assets, the LBF’s directors immediately sought to build relationships with grantees in each area—whom they referred to as “partners.” Relying on these partners to identify needs and set priorities, the LBF deepened these relationships and narrowed its focus over time to identify major, dispositive grants that would have a significant impact on the community. These grants were made over several years as the foundation spent itself out of existence in 2021.

In 2017, at the urging of others in the field and as one of its final gifts to the philanthropic community, the LBF engaged Vantage Point Historical Services, Inc. to help the foundation document its history. This work produced four case studies reviewing and analyzing the LBF’s 35-year record of work. Based on research in the LBF’s archives and interviews with the foundation’s directors, grantees, and other partners in San Diego, these case studies provide an overview of the strategies deployed and the foundation’s perspective on lessons learned from its grantmaking in San Diego.

Building Resident Capacity to Address Community Need

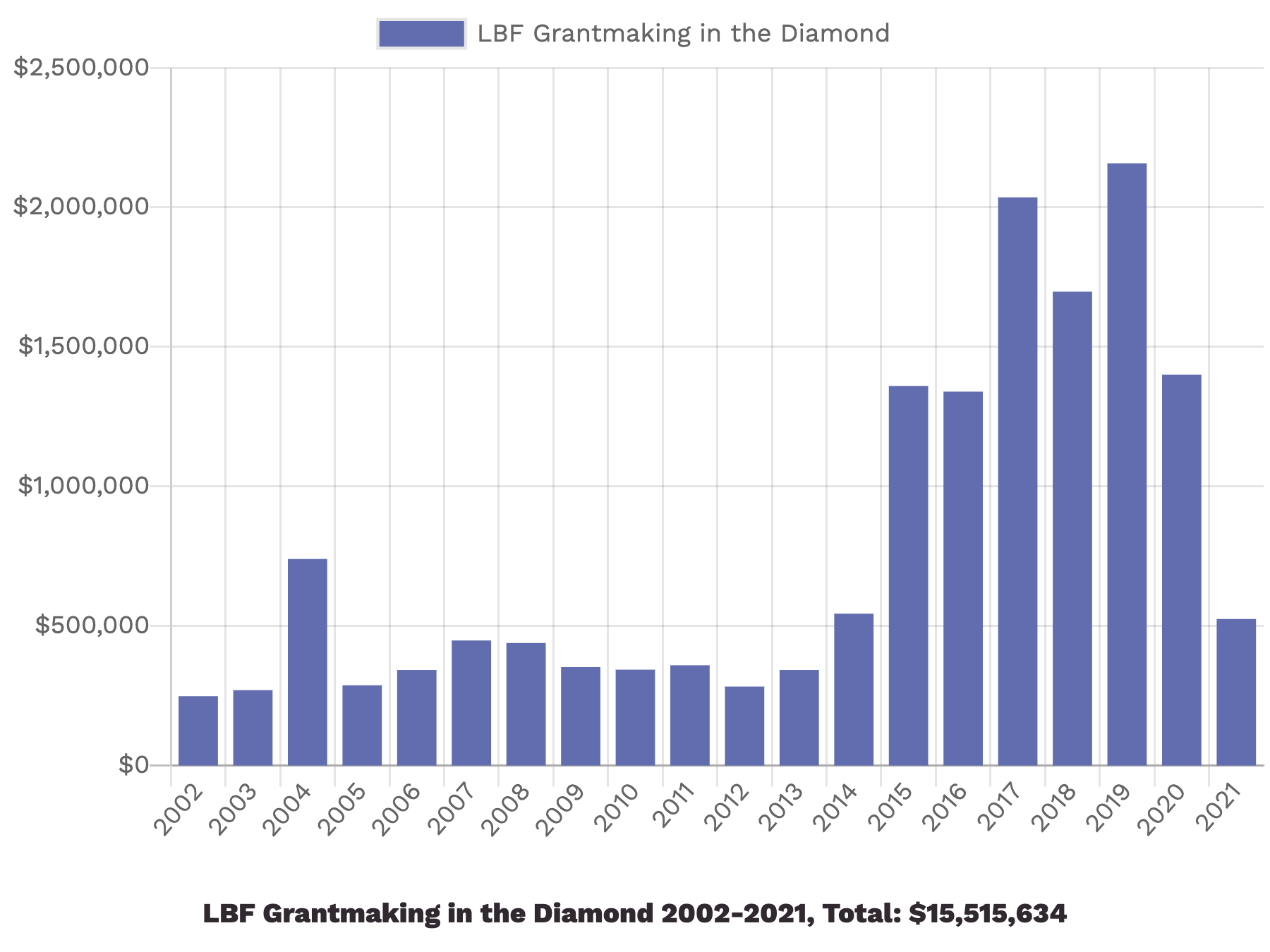

Private foundations have long sought to serve disadvantaged communities as residents strive to tackle economic and social challenges. For decades, people in the Diamond Neighborhoods in southeastern San Diego battled patterns of disinvestment that limited their opportunities to enhance individual and collective well-being. In 2001, the Legler Benbough Foundation (LBF) began talking to residents about how the foundation could help.

The LBF became interested in the Diamond because the needs were great and it recognized an opportunity to leverage resources by collaborating with another major funder—the Jacobs Family Foundation. The two funders shared a common goal: to help residents create and sustain community-building assets and organizations. They also shared a philosophy: listen to the people, understand their needs, build relationships, develop a shared vision, provide funding and support, and get out of the way. For Jacobs, this effort was based on a philosophy of “resident-led” development. For the LBF, it reflected a “relationship-based” approach to philanthropy. Throughout this work, both funders faced a common challenge: how to build trust in a neighborhood where broken promises had eroded trust.

The collaboration with Jacobs went well and much was accomplished. In 2011, however, Jacobs changed its leadership. This change effectively ended the collaboration. Thereafter, LBF continued its relationship-based grantmaking strategy. It worked with grantees to accomplish shared objectives and develop sustainable strategies as the foundation completed its spend-down process.

The LBF’s work in the Diamond illustrates how a funder, working with and learning from grantees, can benefit from their perspective, knowledge, and wisdom to accomplish things that would not have otherwise been possible. It also raises issues related to working with a funding partner, adjusting to changes in circumstances, and the impact of a spend-down strategy in an area like the Diamond. (See sidebar The LBF Grantmaking Strategy in the Diamond.)

Establishing a Focus in the Diamond

In 1998, as the directors of the Legler Benbough Foundation began to formulate their grantmaking strategy, they established the need to address health, education, and welfare programs for disadvantaged families and individuals as one of three major focus areas for grantmaking. (See Governance case study.) Although they chose to limit grantmaking to within the city of San Diego, the LBF’s directors recognized that there was a lot of need that would fit within this broad umbrella. To be effective, they would need a narrower focus.

While they were still settling Benbough’s estate and working to establish the foundation’s grantmaking strategy, the directors made a variety of small grants to help them understand the needs of disadvantaged communities and the opportunities the foundation might have to make a difference. Many of these grants went to organizations working in San Diego’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods, including Big Brothers Big Sisters, the Boys & Girls Clubs of San Diego County, Elderhelp of San Diego, and the Center for Community Solutions, which was working to address domestic and sexual violence. As the directors, Peter Ellsworth and Tom Cisco, thought about how to focus their program, they considered targeting particular neighborhoods in southeastern San Diego where the needs were greatest.

Through conversations with friends, colleagues, and grantees, Ellsworth, as the LBF’s primary grantmaker, learned about work that another private foundation had launched three years earlier in the Diamond. The Jacobs Family Foundation (JFF) was created in 1988 by Joe Jacobs, a highly successful engineer and entrepreneur, and his family. Jacobs wanted to empower disadvantaged communities by giving them tools to address the challenges they faced. Joe also believed that helping people become owners and entrepreneurs was key to breaking the cycle of poverty. To make good on these convictions, the Jacobs family chose to invest all of JFF’s philanthropic resources in the Diamond Neighborhoods. In 1995, JFF established the Jacobs Center for Neighborhood Innovation (JCNI) as a separate operating foundation and set out to organize residents of the Diamond to create a vision for their community and to support the process of implementation. The JCNI promoted a strategy called “resident led community development” that envisioned the physical relocation of a foundation into the neighborhood it hoped to serve. Being in the community would allow the funder to work with residents and rely on their judgement in making grant initiatives.

While the Jacobs Family Foundation was the largest funder of this initiative, CEO Jennifer Vanica and various community leaders recruited other funders to help. Vanica had worked for Peter Ellsworth at Sharp Health Care. When she heard that he was leading the grantmaking effort at the Legler Benbough Foundation, she reached out to him. In 1998, the LBF gave $7,500 to the San Diego Grantmakers to support “The Diamond Collaborative” (later called San Diego Neighborhood Funders). This became the first in a series of early grants the LBF made to JCNI as a way to learn more about what was going on in concert with other funders who were participating in the project.

Ellsworth was intrigued for a number of reasons. As he wrote in 2001, in low-income neighborhoods like the Diamond, “the endless expenditure of funds on social agencies that address the problems created by a dysfunctional neighborhood will solve very little in the long run.” He was looking for a more systemic, comprehensive approach that would strengthen the ability of residents in these neighborhoods to shape their own destiny. Moreover, given the limited scope of LBF’s assets, he hoped to find a partner or partners to leverage the impact of the foundation’s investments.

One of the main reasons we involved residents was because we didn’t want to assume what this community needed. We wanted to hear it directly from the residents.Jennifer Vanica, former president and CEO of the Jacobs Family Foundation

Several factors ultimately convinced Ellsworth and the LBF to focus on the Diamond. He knew Vanica and trusted her work. When he met Joe Jacobs, he was inspired by Jacobs’ vision and his focus on enhancing the capacity of the community. Ellsworth felt that this approach was very much in line with Legler Benbough’s own sentiments, and he appreciated Jacobs’ efforts “to engage the residents in every decision as a means of developing the expertise to change their own community.” By working with Jacobs, the Legler Benbough Foundation could do more than leverage its financial investments—it would have an ideological partner with whom it shared core values, which would generate more creativity and efficiency along the way.

Another, structural piece of the JFF’s strategy aligned perfectly with the LBF’s plans. Jacobs was also a spend-down foundation, and Ellsworth believed that the two organizations would be similarly motivated to identify and make final dispositive grants in a way that would “accomplish something” in the Diamond. Gradually, as the LBF was finalizing the development of its own strategy for grantmaking from 1998 to 2002, the foundation began awarding money to various JCNI efforts. By 2002, these grants totaled $167,500.

Key Insights:

Like many new foundations, the LBF began its work by making small grants to get to know and understand what grantees were doing. In the Diamond, these grants and related conversations led the foundation into conversations with various potential grantee partners. Collaboration with Jacobs offered the potential for greater leverage and greater impact. The decision to work with Jacobs was shaped by existing personal relationships, the vision that Joe Jacobs provided, and the apparent alignment of spend-down strategies. Jacobs’ emphasis on building neighborhood capacity by working closely with the people they wanted to serve would be important in developing Benbough’s strategy in all of its focus areas.

Study Questions:

What historic economic, cultural, and political factors have disadvantaged low-income communities?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of a place-based approach to philanthropy?

How can small grants help funders and grantees get to know one another and explore opportunities to collaborate?

How can smaller funders combine forces with larger foundation partners to achieve greater impact? What challenges will such partnerships face?

Was the LBF’s focus in the Diamond sufficiently narrow to be effective?

Building Relationships With Grantees

Peter Ellsworth had no interest in being a passive investor in either JCNI or the Diamond Neighborhoods. The LBF’s grantmaking strategy was focused on building deep relationships with grantees. He soon began attending JCNI’s community meetings in the Diamond and quickly realized the challenges that Jacobs had to overcome. “There was anger about foundations and programs that had come to the neighborhood, made promises and then left with the residents worse off than before,” he said. There was a sense that “the neighborhood had been studied to death by outside organizations,” Vanica noted, “and little had come from it.” Many people in the community felt that they had been disrespected because of their race or economic status. They had also been given very few resources to support collaborative work and thus had less experience working in groups or listening to diverse points of view.

After a long legal career and a decade of service as the CEO of a large healthcare organization, Ellsworth felt he had a lot to learn to understand the Diamond and its residents. He was used to systems with well-established institutions that funneled information up to leaders who were clearly empowered to wield the resources at their command to get things done. In the Diamond, the institutional landscape was fractured. Some people who attended the Jacobs meetings spoke loudly and passionately, but they had no following. Other people were less vocal, but were well-connected to social networks that didn’t always have a clear institutional basis but could be effective in shaping community action.

Ellsworth noted that frequently when the Jacobs team organized meetings they “faced the confrontation and stayed for more.” By doing so, they began to build a foundation for mutual respect and trust. If the LBF hoped to accomplish something in the Diamond, it would have to do the same thing. Very quickly, the LBF’s approach to the Diamond began to move along two tracks: grants to support JCNI and its resident teams, and grants to nonprofits in the community, some of whom were working with JCNI while others were not.

In this early stage of the work in the Diamond between 2003 and 2005, to learn more about the neighborhood, the LBF gave grants to Angels Foster Family Network ($30,000), a nonprofit created to support foster children; Homey’s Youth Foundation ($15,000) to aid the California Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) program in the Diamond Neighborhoods; Pazzaz ($10,000), an academic enrichment program for low income children and their families; and Second Chance ($20,000), an organization that provided job readiness, life skills training and safe affordable transitional housing to people struggling with addiction; the Family Literacy Foundation ($20,000); and the San Diego Family Justice Foundation Center ($60,000). Many of these initial grants went to organizations that were working in other parts of San Diego as well as the Diamond. These grantees were attractive because they were proven organizations with clear capacities to utilize the foundation’s resources and to help the foundation learn more about working in this field. Nearly all were focused in one way or another on creating programs for neighborhood youth.

These grants also gave the LBF some visibility in San Diego and especially in the Diamond, which opened opportunities to work with fledgling social entrepreneurs. Twenty-five year old Chris Rutgers, for example, sent an unsolicited letter of inquiry about a program he had created to give disadvantaged teens affected by trauma opportunities to experience the outdoors in ways that would build their self-confidence. A former professional skier, Rutgers had self-funded Outdoor Outreach for two years, but was running out of money to keep it going. When Ellsworth met with Rutgers, he was impressed with his entrepreneurial vision, commitment, and business plan. In 2003, the LBF made a $5,000 grant to the project. This was the beginning of what would become a major partnership.

Through JCNI, the LBF was also introduced to several nonprofits that were already working with the Jacobs initiative. The Elementary Institute of Science (EIS) was a nonprofit science enrichment program that had been created in 1964 as an after school project at Kennedy Elementary School. For decades the program had operated out of an old home donated by the City of San Diego. The organization was trying to raise $6 million to build a new 15,000-square foot science center. When Jennifer Vanica and JCNI began working in the Diamond, EIS was one of their first partners. The LBF came alongside this effort even before it had committed to working in the Diamond by providing a $10,000 grant to support the capital campaign. Over the next four years, as the foundation deepened its commitment in the neighborhoods, it delivered an additional $40,000 in grants to EIS. With the support of many other funders, EIS was able to build its new center.

As the LBF continued to narrow its focus to the Diamond Neighborhoods for all of its health, education, and welfare work, it made grants to organizations whose offices were not in the Diamond, but who were providing services in the neighborhoods. In 2004 and 2005, the LBF awarded grants to the Aquatic Adventures Science Education Foundation for ocean-related science education at Encanto Elementary School in the Diamond, Big Brothers for a mentoring program at Valencia Park Elementary, and the Girl Scouts for local mentoring in the schools. Although these were worthwhile projects, it became apparent that to maximize impact and to have the funds make a difference, a further narrowing of focus would be necessary. Accordingly, the foundation changed its grants criteria in 2010 to support only organizations that had their offices located in the Diamond.

In working directly with potential grantees, the LBF began to see opportunities for greater grantmaking. At the Jackie Robinson YMCA, for example, Executive Director Michael Brunker said the Y’s greatest challenge was in getting people to the Y in an often-dangerous neighborhood, especially children coming after school or on Saturdays. The LBF and Brunker discussed buying a bus. As they looked into it, Brunker discovered that he could buy several used buses for the price of one new one, so the LBF gave the Y a grant to buy the used buses. The buses provided transportation to the Y and served many other organizations in the Diamond.

A set of critical issues facing children in the Diamond stemmed from the combination of poor or inappropriate diets, a lack of places to exercise, and the lack of role models. These circumstances contributed to an increasing number of overweight, diabetes-prone young students. When the nurse at Horton Elementary School in the Diamond reached out to the Whittier Institute of Diabetes to test the students for pre-diabetes, the LBF offered a three-year grant of $155,789 and other funders provided resources to support programs to help students change their diets and activity levels. The program was successful and helped change the culture at the school to benefit many students.

While working with Jacobs, other opportunities arose. Community residents were striving to prevent increases in gang activity in the neighborhoods. In 1999, for example, gang-related vandalism and graffiti were a major problem. After some teenagers tagged one of JCNI’s vacant properties, instead of having them thrown in jail, JCNI donated space and materials to provide a constructive outlet for their graffiti art. This project, originally known as “Graff Creek,” engaged more than 300 youth in its early days. It was renamed Writerz Blok in 2000. Jacobs then donated a half-acre lot in 2003 as well as office space and exterior space for an open-air art park to become one of the nation’s first graffiti parks. Intrigued with the concept, Ellsworth and Cisco made a site visit in April 2004 and began funding the project. As Elllsworth would later note, “The development of the Writerz Blok project directly related to the treatment of underlying issues rather than the result of the problem. By respecting these artists and by learning from them, so-called criminal behavior became respected art.”

The LBF was given the opportunity to further this approach because of the foundation’s relationship with the Museum of Modern Art in La Jolla. At a meeting with the director, Ellsworth talked about Writerz Blok and its potential ties to the broader art community. The director said: “We are building a new facility downtown, why not have them do graffiti on the construction fence?” The people at Writerz Blok embraced the opportunity and the museum held an event at which La Jolla Patrons of the Museum visited the graffiti-painted construction fence and learned about Writerz Blok. Museum members later ranked the event as one of the year’s best. The showcase was rewarding for the graffiti artists and led to numerous opportunities for them to exhibit their art.

These early grants convinced the LBF that the work in the Diamond offered an unusual opportunity to make a difference and address strategic change to provide the impact the foundation hoped to achieve. Ellsworth described the efforts of the Jacobs Family Foundation as “community capacity building” or an effort to “train the community to deal with its own needs.” He told the LBF board in August 2005 that this strategy was “not without its risks, but it is a model that at least attempts to get at the underlying issues.” With Jacobs on the scene, grantmaking, especially for a very lean organization like the LBF with directors serving as staff, could be much more efficient and, hopefully, effective. The LBF also liked the collaboration because it still allowed the foundation to establish its own relationships with community groups.

These relationships were critical to the LBF’s emerging approach to grantmaking. Relatively new to philanthropy, Ellsworth was eager to learn as much as he could about the field of philanthropy. By 2005, he had joined the board of San Diego Grantmakers. When the organization hosted the annual meeting of the Council on Foundations in San Diego in April that year, he attended many of the sessions. He was stunned by much of what he heard. Many of his new colleagues in the field seemed to think that they were the main agents of change and not their grantees or the communities they represented who possessed the ideas to address problems in the field. In one session he listened as a speaker coached funders on how to avoid being drawn into relationships with grantees in order to avoid dependency. Ellsworth was appalled. He believed that “a personal, sustainable relationship with the grantee is necessary.” Indeed, as he had come to appreciate from talking to residents and leaders in the Diamond Neighborhoods, “Until this relationship develops, the power dynamic of grantor-grantee prevents the kind of cooperative thinking and dreaming that forms the basis for creative grants to address shared objectives.”

Key Insights:

The Legler Benbough Foundation chose to focus its health, education, and welfare program on the Diamond Neighborhoods because the needs were great and JCNI represented a highly compatible partner. In the early years of grantmaking in the neighborhoods, LBF gave grants directly to JCNI to support various community initiatives. It also worked independently with community organizations, some of whom were associated with Jacobs. These grants helped build relationships with the staff and residents associated with JCNI, as well as other grantees in the community. Committing time and talent to these relationships—as well as money—Peter Ellsworth, as the foundation’s primary grantmaker, listened and learned and came to believe that a deep relationship with grantees fueled creative and effective grantmaking.

Study Questions:

What are the potential risks and rewards of a relationship-based approach to philanthropy in disadvantaged communities?

How can philanthropists overcome the inherent power imbalance in the funding relationship and build the trust necessary to nurture partnerships with grantees?

How can relationship-based grantmaking be personally transformative for funders and grantees? How can these relationships impact the work?

When forging partnerships with other grantmakers, how can a funder maintain the right balance between collaboration and independence?

The Partnership in Jacobs Projects

As it developed its work in the neighborhood, JCNI evolved to include a wide variety of operations and projects. It envisioned four streams of funding including: independent grants, single-issue collaborative grants, blended grants across areas of interest, and blended capital (including grants, equity, PRIs, bank loans, loan guarantees, and linked deposits) to develop physical and social infrastructure in the neighborhoods. JCNI began recruiting a variety of potential funders into this effort, including public agencies, private financial institutions, and philanthropists.

Many of these funders, including the LBF, were part of a neighborhood funders initiative. Funder collaboratives are not easy and working with San Diego Neighborhood Funders was no exception. Although the participants were collegial and passionate about helping, participating foundations had their own agendas and missions, and, in the case of most of them, decisions on specific grants took time to be processed before they were finally approved. Ellsworth quickly learned that in building relationships with grantees and meeting with residents, the LBF’s ability to make decisions on the spot was very helpful. It also represented a way of sharing power because the grantees were present and able to advocate for an idea as the decision was being made.

Most of the other donors working with JCNI, as Jennifer Vanica has noted, chose to fund “down.” They focused on specific fields of interest. Meanwhile, JCNI and the LBF funded “across” the community to provide “the connective glue” that supported “community organizing and working teams, building social networks, managing cross-sectoral partnerships, cross-cultural understanding, and action learning.”

The LBF focused initially on youth, and at one point, the foundation even considered targeting all of its resources in the Diamond on education-related work. The LBF supported efforts to enhance the teaching of science, but it was reticent to become too deeply involved with schools and particularly the bureaucracy of the San Diego Unified School District. During this time, additional projects were developed using the arts as a way to enhance community pride and self-confidence. Disinvestment, poverty, and high crime rates in the community meant that residents, especially young people, had fewer structured outlets for personal growth and development. Creative and artistic expression offered one way to cultivate a sense of identity and voice while preparing young people to learn how to relate to an audience.

As the concept of a neighborhood commercial and cultural center (Market Creek Plaza) developed, the idea surfaced that local artists could paint portraits of local community leaders and unsung heroes to be displayed on the side of the buildings. Members of the community were brought together to identify the leaders that the community wanted to honor. Attending these sessions, Ellsworth again had the opportunity to learn from the residents. He came to understand what leadership qualities they valued. The “Community Faces Project” demonstrated respect for community residents and an appreciation of their work, which was an important element in the ultimate goal of building resident capacity to lead and govern.

The LBF also realized that as JCNI increasingly relied on the perspective and guidance of local residents, various projects reflected their insight and knowledge in addressing local issues. It was the residents, for example, who came up with the idea of using a floating stage to allow an amphitheater to be built on the banks of a creek. It was the residents who had the vision to use textile patterns to add culturally significant color, patterns, and decoration to the Plaza. It was the residents who proposed designating a wall in the Plaza to be decorated by children. All of these experiences convinced the LBF that to have an impact, it was critical to build personal relationships with grantees by listening and learning from them.

Like many funders, Ellsworth often tried to connect the various programs that the LBF was working on in its three program areas. When he was in Balboa Park, he thought of the Diamond Neighborhood communities which were so close to the park’s institutions and yet separated by a huge social and cultural barrier. When he was at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) discussing investments in science, technology, and innovation, he thought of ways to join the Diamond to the university’s prosperity engine.

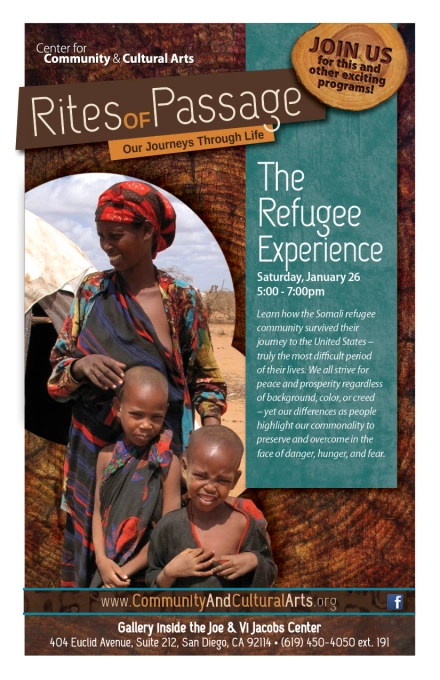

Late in 2007, as JCNI was nearing completion of the Joe and Vi Jacobs Community Center (an office building and community event center), the LBF began to consider the idea of leasing a space in the center to host an artist-in-residence program and exhibitions from various Balboa Park institutions. The idea seemed like a win-win for everyone. The museums in Balboa Park would become more inclusive and better able to integrate the cultural resources of the community into their programs. The community in southeastern San Diego would have more opportunities to present and celebrate its diverse cultural traditions and artistic expressions on a bigger stage. In December, the LBF made its first commitment towards the development of this idea when the board approved a $51,750 grant to lease and pay for improvements to the gallery space in the new Jacobs Center.

The Joe and Vi Jacobs Center opened on May 21, 2008. Over the next several years, the LBF worked with residents of the Diamond, staff at JCNI, and institutions in Balboa Park to mount exhibitions in the gallery and to develop a concept for a permanent community art center. Ellsworth shuttled back and forth between the Park and the Diamond to try to catalyze interest and relationships. In February 2009, he gave a draft prospectus for the Benbough-Jacobs Center for the Arts at Market Creek to the director of the San Diego Museum of Art (SDMA), who expressed interest in the project. SDMA was already working with Market Creek, and the museum was very keen on the opportunity to cultivate future staff and leadership to build relationships with traditionally underrepresented communities in the San Diego area. SDMA also thought it might be able to bring other funders to the table. These conversations led to an initial pilot project—simultaneous exhibitions at SDMA and the Jacobs Center of components from a national traveling exhibition on “black womanhood.”

The success of the exhibition on black womanhood accelerated the conversation around the development of a community art center. In the fall of 2009, the LBF sent out a request for proposals looking for a consultant to lead the process of developing a collaboration between residents of the Diamond, the LBF, and the museums in Balboa Park. Ellsworth also enlisted members of the Multicultural Arts Leadership Initiative, which was scheduled to meet in San Diego, to do a workshop on the proposed project. Ellsworth characterized this as a “listening phase” in the project’s development to understand the views and objectives of the neighborhood and the museums in Balboa Park before moving forward with a concrete plan.

During this listening phase local leaders were recruited to help develop the concept for a new Center for Community and Cultural Arts at the Jacobs Center. But it was slow going as the LBF and Jacobs worked carefully to ensure that these were community-led initiatives. LBF board members expressed concern that “fine art” exhibitions in the Diamond would not be well-received. Ellsworth urged patience. To be successful, the community and the museums had to develop a sense of community ownership of the new gallery. The future of the project, he said, would be determined by the process, and it was important “to let the process make the decisions.”

In November 2010, to underscore the community’s leadership, Ellsworth invited Jihmye Collins, a member of the guide team and the learning partnership working on the project, to speak to the LBF board. This move underscored the nature of the foundation’s relationship with leaders in the Diamond, giving them opportunities to make their case face-to-face to the board, rather than through a mediated paper-based application process, and to discuss strategies for community development in the Diamond.

This strategy really gained ground as the museum, residents, and local artists began to work together to create a special new exhibit for the center. The residents came up with the title “Rites of Passage,” a concept that provided an opportunity for each of the cultural groups in the Diamond to exhibit articles that were relevant to this life event in their culture. As the committee of residents and museum directors began to review potential items for exhibit, the museum personnel were awestruck by the quality of the objects and artifacts that came from residents and their families and the ways in which they represented the diversity of cultures and histories within the Diamond community.

Rites of Passage opened in 2012 in the Jacobs Center gallery, where it remained for several months. It attracted national attention as it hosted representatives from foundations and art organizations all over the US. More important, the exhibition was embraced and celebrated by the community and connected the Diamond with people from throughout the region and beyond. After the exhibit closed, it was moved to the Museum of Man in Balboa Park, whose director had been a principal advisor to the project. After the move, community residents continued to visit the exhibition to see their materials presented with honor and respect. This experience represented a high point in the LBF’s collaboration with JCNI. According to Ellsworth, it “developed capacity in both the residents and the museums. It was a profound experience for everyone.”

Key Insights:

Working with a major funder located in the Diamond Neighborhoods with similar strategies for working with residents produced beneficial results that would not have been possible otherwise. The LBF was also able to leverage personal relationships with grantees in other program areas to promote collaborative projects between people and institutions that ordinarily had little contact with one another. The foundation learned that the best ideas for what will work come from the people whose lives, communities, and institutions will be most affected by the projects or programs that a donor may choose to fund.

Study Questions:

What are the structural challenges inherent in trying to create funder collaboratives? How can these challenges be addressed?

How can funders encourage elite institutions to listen to and respect the cultures of communities that have been historically marginalized?

How can a relationship-based approach to philanthropy lead to higher-impact projects and programs?

When one foundation is working in partnership with another, what is its obligation to consult with its partner before making a decision to change direction?

Formal grant applications and grant reporting are a common practice for many foundations. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this approach compared to the LBF’s preference for face-to-face interactions and reporting?

When Partners Change Course

In 2004, Joe Jacobs died and his inspirational leadership came to an end. Over the next seven years, JCNI continued to grow and to broaden its portfolio of work. By 2011, the organization had acquired 52 of the 60 acres of blighted real estate that residents wanted cleaned up and developed as part of a village envisioned as a commercial and cultural hub. The City of San Diego had approved the necessary general plan amendments that rezoned the land, and plans were moving forward to add a Walgreens, a community clinic, and affordable housing.

But in 2008, the onset of the Great Recession led to extraordinary challenges. The unprecedented downturn forced community businesses to close and banks to put lending on hold just as Market Creek Plaza loans were due to be refinanced. When the markets crashed, financing froze, property values dropped, and development stalled.

In 2011, JCNI decided it needed a change in leadership. For Ellsworth, the departure of Jennifer Vanica and her husband, who served as chief operating officer of JCNI, represented a personal and an organizational blow. He had developed a great deal of respect for the work she was doing at JCNI. The LBF also perceived that the leadership change gave rise to deep concerns about Jacob’s future direction.

Although shocked by the changes, the LBF was aware of the contributions made by Jacobs to the community and the good intentions of its leadership. The LBF continued discussions with and grants to Jacobs through its leadership and organizational changes. But, in the aftermath of changes at JCNI, Ellsworth felt personally and institutionally vulnerable. When Jacobs made its decisions, the LBF was unable to explain the situation to the residents and grantees it was working with. And, as Jacobs made staff, activity, and organizational changes over time, it became clear to the LBF that its strategy of developing personal relationships with grantees in the neighborhood and working with them to build projects and programs could not be successfully pursued with the perception that the LBF was continuing as a partner with Jacobs.

Key Insights:

The experience with Jacobs clearly demonstrated the enormous benefit to a small foundation in working in partnership with a large established entity. Much was learned and accomplished that could not otherwise have taken place. The LBF also learned that there are substantial risks when foundations partner with other funders and become closely associated with them in the mind of the grantees. Funders who enter into such relationships may be affected by decisions and held accountable for actions over which they have no control.

Study Questions:

What factors lead foundations to change their strategies or funding priorities?

How should a foundation communicate with grantees and partners about changes in its program or grantmaking?

If a foundation changes direction or priorities, does it have a moral responsibility to provide resources that will ease transition for its grantees or partners?

Focusing on Relationships, Old and New

In the wake of the changes at JCNI, the LBF focused on its relationship-based approach, fundamentally empowering the foundation’s partner grantees with the ability to shape the foundation’s strategy. After discussion with grantees and others in the community, in 2014, the LBF evolved its strategy to include three potential areas for funding: 1) continued support for non-Jacobs controlled independent organizations in the Diamond, especially where the LBF had already established a working partnership; 2) possible support for some Jacobs projects that evidenced success, but not as a Jacobs partner; and 3) possible help to organizations seeking to become self-sustaining in the event of a loss of funding from Jacobs. As time went on, the foundation’s focus was almost entirely on the first of these strategies. Fortunately, even before the changes at Jacobs, the LBF had built many of its own relationships with grantees. These relationships, in combination with new partnerships, formed the basis of the LBF’s remaining work in the Diamond as the foundation’s assets were disbursed.

One such relationship was with Barry Pollard, a local community organizer. He had an idea for developing what came to be called the Urban Collaborative Project. Pollard was in his late fifties. He had been born and raised in southeastern San Diego when the community was dominated by African-American families. After college, he went into the field of human resources and eventually became a director of human resources for Kaiser Permanente. When he retired, he became a community activist and ran unsuccessfully for city council in 2010. Despite his loss, Pollard continued to look for ways to strengthen the fabric of the community, and he reached out to the LBF.

Typical of the LBF’s relationship-based approach, Ellsworth sat down at a dining room table to talk about Pollard’s idea. With an initial grant of $35,000 from the LBF, Pollard’s vision came to fruition in 2014 when the Urban Collective Project (later Urban Collaborative) was established to mobilize residents in southeastern San Diego to identify issues such as safety, civic engagement, health, and infrastructure. The project’s first major initiative involved a community organizing forum in the Valencia/Lincoln Park area. At the meeting, the group decided to focus on getting better quality food in the local grocery store. After community members wrote to the CEO of Kroger grocery, the company agreed to make a $1 million investment in upgrading the store.

Another long-standing relationship was with Gompers Preparatory Academy. In 2013, Vincent Riveroll, the director, called Ellsworth for guidance. The school was facing a cashflow crisis because of delays in the State of California’s payments to the charter school. LBF directors approved a program-related investment (PRI) loan to help ensure that staff would get paid in the months of May, June, and July while the school waited for the state money to arrive. When these monies came in, the school repaid the PRI in full.

The LBF’s arrangement with me is that I meet with Peter Ellsworth every quarter. We go through an action plan. We may not succeed all the time but we’re moving forward and we’re staying focused. That helps us stay accountable. We move forward in milestones, and if we’re falling behind, Peter helps us get some training. That’s the kind of help I think more foundations should be mindful of.Barry Pollard, founder of the Urban Collaborative Project

These initiatives and others fueled the LBF’s grantmaking in the Diamond in this new era. In 2013, grants to the Diamond totaled $342,500. Many of these grants reflected the deepening of partnerships, particularly with organizations like the Elementary Institute of Science, Outdoor Outreach, the Jackie Robinson YMCA, and Gompers Preparatory. But Ellsworth was also excited about new entities like the Urban Collaborative.

At the same time, the LBF was also exploring other new partnerships that had the potential to develop high impact sustainable programs. In 2013, for example, the LBF joined with other funders to provide the first of a series of major grants to Teach for America to launch a chapter in San Diego to recruit and train teachers to work in low-income schools and particularly with Gompers. The following year, it began funding the National Conflict Resolution Center (NCRC) based in San Diego. NCRC was engaged in providing training to people in conflict situations. Working with NCRC, a center was established in the Diamond. In addition to dispute resolution, working with NCRC’s Steve Dinkin and the Sheriff’s Department, the LBF funded the development of a restorative justice program at Lincoln High School that aimed to reduce tensions in the neighborhoods and head off violent confrontations. Over the next several years, the LBF provided $537,600 to support this initiative.

Key Insights:

Following the changes by its partner JCNI, the LBF was able to build on its existing and new relationships in the neighborhood to achieve major goals. The insights gained from years of grantmaking had deepened the LBF’s understanding of the systemic challenges facing the Diamond Neighborhoods. These insights, in turn, helped the foundation forge relationships with social entrepreneurs focused on filling gaps in the social infrastructure. In collaboration with residents and the LBF, these grantees developed programs and projects that aligned with the foundation’s mission and goals.

Study Questions:

If big dreams inspire, but overcoming challenges leads to disappointment and mistrust, how can funders strike a balance between ambition and pragmatism?

How can a funder mitigate the reputational risks it faces when it partners with another funder?

When start-up or grassroots organizations lack an institutional track record, how can a relationship-based approach to philanthropy satisfy the funder’s need for due diligence?

How can the funder and grantees work together to set realistic goals and establish appropriate strategies for tracking accomplishments and measuring impact?

The Spend Down of Assets

In their conversations with Legler Benbough, Peter Ellsworth and Tom Cisco had always understood that their job was to spend the assets of the foundation within their lifetimes in order to maximize the impact of Benbough’s legacy and ensure that the donor’s intent was carried out by people who knew him. In the early days of the LBF’s work in the Diamond, Ellsworth had imagined that when it came time to spend out the foundation’s assets, it would probably make a large dispositive gift to JCNI, but with the changes at Jacobs, the LBF decided to pursue other options.

In a memo to the board, Ellsworth tried to summarize the lessons the foundation had learned in the Diamond. He recognized that in many cases trying to develop projects in the neighborhoods that would have a significant impact “would require resources far beyond our capacity.” Unlike the Science arena where a sophisticated set of institutions constantly communicated with one another and funders and maintained statistics, progress in the Diamond was much harder to measure. Community indicators tracked changes in health, education, and welfare in the neighborhoods, but other benchmarks and measures were needed to assess the evolution of programs and institutions that would drive these population-based changes. The LBF believed that these measures were much more challenging to develop in the complex world of comprehensive community change, and as Ellsworth noted, it was “beyond our capacity to stay abreast of” the changes taking place in the community. Rather than invest in statistical evaluations of progress, the LBF preferred to rely on face-to-face interactions and reporting to satisfy its need for monitoring and evaluation.

Since a major partnership with Jacobs was not in the cards going forward, the foundation needed to continue to develop its existing relationships and work with other grantees. Most of the community organizations that were based in the Diamond operated with relatively low budgets and small staffs. Giving a large dispositive grant to an organization like this could do more harm than good, prompting organizations to grow beyond their capacity to sustain newly inflated budgets. So the time it would take to spend down the LBF’s assets had to be expanded.

All along, the LBF’s telescoping focus approach to grantmaking and its ultimate spend down had been to engage with grantees, learn from them, work with them to understand their capacity, and deepen the relationship and level of commitment as it became clear that they had the ability to make a difference in the community. As early as 2008, the foundation had begun to outline criteria to identify long term partners called “dispositive grantees,” meaning that they were the kind of grantees that should share in the ultimate distribution of the foundation’s assets. In identifying these grantees the foundation was focused on organizations and projects that were creative and innovative and would be sustainable long after the LBF had gone out of business. It was particularly interested in efforts that promoted collaboration among various institutions or would contribute to a long-term process of systemic change in the neighborhoods. As time went on, the LBF looked increasingly for organizations with strong leadership at the executive and the board level.

One by one, starting in 2015, the LBF started to make these larger dispositive grants, some payable over a number of years. Most reflected the culmination of a long relationship with the grantee or the community. In some cases, the final dispositive gift sought to enhance a physical asset in the community and also provide an important support system for civic engagement. An opportunity arose when a new downtown library created space for a program that had been previously located at the Malcolm X Library in the Diamond. Jay Hill, the CEO of the San Diego Library Foundation, approached the foundation with the idea of creating a Teen Lab at the Malcolm X Library. Ellsworth liked the idea, but he was concerned about whether the big library organization really understood the needs of the local teens. He told Hill that the LBF would consider funding the project but only if local residents came up with plans for what they wanted the center to provide. Ellsworth introduced Hill to local residents who led the sessions and created a kind of advisory group for the center. The results of these studies reflected many things that were not on the library’s or the LBF’s agenda. One of the concerns of the residents, for example, was that the library be open for extended hours so that the teens could use the center. The board of the LBF held its quarterly meeting in the space and reviewed some of the recommendations of the residents. The board was impressed with the emphasis on the use of digital equipment with the hope that this would help mitigate the very significant digital divide that was adversely affecting so many residents in the Diamond. With the City’s agreement to extended hours, LBF funded the project with $1 million for construction and endowment. The San Diego Library Foundation was so impressed with the results of the teen involvement that it used this model for other teen centers that they developed.

As the foundation gave a green light to the Teen Lab project, Ellsworth was also working with an unlikely team of former political rivals who had come together to develop a new generation of community leaders in the Diamond. In an earlier era, Tony Young and Dwayne Crenshaw had run against each other for City Council. Young was victorious, and he served until 2012 before stepping down to become executive director of the American Red Cross chapter for San Diego and Imperial Counties. Crenshaw went on to run several nonprofits before he teamed up with Young in 2014. Young and Crenshaw perceived a critical need to identify and support local leaders in the community, and they proposed creating a new organization called RISE San Diego to offer various leadership programs to disadvantaged communities. In 2015, the LBF provided $50,000 to launch the initiative. In 2017, it offered another $197,940 to ensure fellowships for emerging leaders from the Diamond. The program was enormously successful, attracting nearly $2 million in additional funding and leading to the election of one RISE alum to the San Diego City Council.

Ellsworth’s work with the RISE founders showed that the nearly fifteen years that the LBF had invested in the Diamond was paying off in terms of a greater understanding of the community and knowledge of its emerging leaders. Still, Ellsworth was interested in building collaborations as an essential component of dispositive grants, and in the spring of 2015, he explored various ideas for youth-centered grants that would involve the Jackie Robinson YMCA, Gompers Prep, and Outdoor Outreach. Although this and other efforts to build collaborations failed to produce a major collaborative initiative, they helped various institutions develop a greater understanding of how their missions were aligned and see the potential for sharing resources and ideas.

The LBF had a long relationship with the Jackie Robinson YMCA. First opened in 1943, this facility had languished for years in one of the most neglected parts of the Diamond Neighborhoods. In 1997, former assistant coach of the Detroit Pistons Michael Brunker became executive director and began working to transform the institution. When the Y launched a capital campaign to build an entirely new showcase facility, the LBF awarded a grant for $2 million to help finance the new gym. Ellsworth also worked with Brunker and philanthropist Buzz Wooley to fund a swimming pool. When Brunker asked how the LBF wanted to be recognized, the foundation demurred until Brunker suggested a memorial that would honor people who had worked out in the gym and gone on to greater accomplishments. The LBF loved the idea and agreed to the plan.

Like the Jackie Robinson YMCA, the Elementary Institute of Science, located next door to the Malcolm X Library, was one of the first institutions in the Diamond to receive funding from the LBF. In 2015, it was in the middle of an organizational transition with the departure of its long-time executive director. LBF provided a $90,000 annual grant to support the salary of the new executive director to give the organization some running room. It later awarded a $500,000 dispositive grant to help develop and implement the organization’s Steps to STEM program. This innovative program provided STEM education to elementary school students in the Diamond on days when school was not in session and soon expanded to serve most of the students in the Diamond.

Over the next four years, other dispositive grants in the Diamond followed: Teach for America ($375,000) to strengthen education in the neighborhoods, Gompers Preparatory ($900,000) to support enrichment programs and operations, the League of Amazing Programmers ($100,000) to fund a collaboration with Gompers that helped students learn how to code, the National Conflict Resolution Center ($714,680) to help underwrite its work in the Diamond, Urban Collaborative Project ($303,000) to support its initiatives in Lincoln Park, and RISE ($700,000) to provide scholarships for fellows. All totaled, by the time its assets were fully distributed in 2021, the Legler Benbough Foundation expected that its grants in the Diamond over the course of its history would total more than $15 million, money that helped many of the foundation’s grantees to accomplish something significant in their community.

Key Insights:

As the LBF considered dispositive grants in the Diamond, the foundation and grantees sought to support creative programs that fostered the sustainability of grantees. To develop these initiatives, Ellsworth worked in close collaboration with grantees to identify high-impact projects that could be accomplished within the time frame of the spend down. Capital investments in new facilities and funds to develop sustainable programs were at the heart of many of these dispositive grants. All of these grants were designed to sustain or grow the institution’s programs. Many also sought to enrich the human capital in the neighborhoods by supporting youth or promoting leadership development.

Study Questions:

What challenges and opportunities does a foundation face when it wants to make large, dispositive grants in a low-income community?

How does a telescoping approach to grantmaking lead to projects with a higher potential for impact?

To what extent can or should funders incentivize grantees to collaborate?

What resources, beyond money, can elite institutions provide to grantees to help them sustain their work?

Additional Insights - Case Study Sidebars

Lessons Learned

The Risks of Big Projects: As a foundation centered upon making an impact and accomplishing something significant, the LBF was naturally attracted to the opportunity to work with other funders to accomplish major systemic change in a San Diego neighborhood. And the foundation, its partners, and their grantees accomplished a great deal. But large-scale, systemic change is very difficult to accomplish in communities that have been struggling with underinvestment for decades. It requires perseverance, a lot of time, and constant adjustment as circumstances change. This presented major risks, especially for a spend-down like the LBF, which has an inherently limited lifespan. When things didn’t work out as planned with the LBF’s funding partners, and their decisions forced the LBF to abandon big plans, the foundation was placed in a very difficult position within the community, especially with those adversely affected by the change. The challenges this presented were deep and difficult, especially since the LBF had such a long association with its partners in the minds of the grantee community.

Partnership with Other Funders: The opportunity to work with other funders and learn from them was critical for the LBF. It could also be frustrating, especially since the LBF was able to make grants on the spot while other funders had separate operating models and objectives, which sometimes slowed the process down. Overall, however, the LBF’s collaborations led to some significant accomplishments that would not have been otherwise possible. As inspiring and helpful as these partnerships were, they were ultimately subject to change. Over time, the LBF learned the importance of maintaining relationships outside its group of funding partners. Doing so enabled it to build out a plan for its eventual spend down after key partnerships came to an end.

Building Grantee Relationships: When it first arrived in the Diamond, the LBF had to contend with the considerable, challenging legacies left behind by foundations and government agencies that left promises to community members unfulfilled. For many neighborhood residents, the LBF and its fellow funders were just another group of rich white people whom they did not trust. Preconceptions ran both ways, and understanding the obstacles this presented took time. The LBF had to listen and learn and demonstrate that it appreciated and respected the work already underway in the community. In so doing, the foundation made strides towards building the kind of trusting relationships it needed to have an impact in the neighborhoods. When it came to building personal relationships, the LBF found it enormously useful to have Ellsworth able to make grant decisions in the field. This allowed the LBF to demonstrate that its work was not about the foundation, it was about the grantees and the work they could accomplish together.

This approach also helped the LBF cultivate a relationship in which the grantees knew they could draw on Ellsworth’s personal expertise and network to develop and complete project ideas. Ellsworth, conversely, was able to demonstrate his gratitude for the opportunity to work with them. The reciprocal nature of this relationship went a long way toward addressing the “power imbalance” that is inherent in any funder-grantee relationship.

Yet there is also a downside to relationship-based grantmaking: the success or failure of the grantee becomes a personal matter for the funder. When the LBF’s funding partner changed course, for example, it felt to Ellsworth like losing an old friend. Meanwhile, when grantees became frustrated and disappointed, the LBF shared those feelings along with the blame. In the end, the rewards of its work made the painful parts of these relationships worth the effort. They formed the basis of major accomplishments, and for the LBF’s directors, were the best part of working in philanthropy.

Measuring Results: Community change is very difficult to measure. Poverty rates, unemployment, and health outcomes tend to track with the larger economy and society, even when good statistics are available for a specific community. Evaluating these metrics can be useful, but it often offers only a superficial perspective on changes underway. After several years working in the Diamond Neighborhoods, the LBF concluded that staying in touch with grantees working on the ground and listening to feedback in the community was a far better way to measure accomplishment.

Solving big, structural issues in education, health, and community safety in disadvantaged areas is a difficult and complex task. The LBF learned that “success” usually meant that it had helped improve one small part of the big picture, but that the work progressed slowly and almost never consistently. With this in mind, the LBF approached its spend down feeling that it had “accomplished something significant” in the Diamond Neighborhoods.

Personal Perspective:

Peter Ellsworth

The experience of working with people of such a different background was new for me. I will never forget at one of the early meetings with residents, one of them looked at me and said, 'You look just like the kind of person that I don’t like.'Peter Ellsworth, president and operating director of the LBF

“When I came into philanthropy, after a Stanford education, after leading a San Diego law firm, and after serving as the CEO of a billion-dollar health care system, it was very surprising and even shocking how people in southeast San Diego, living in my community, could have the perspectives that they had of me, of the law and law enforcement, of our government, of philanthropy, and just about everything else.

Once, when I was visiting with some neighborhood residents, one young man told me I looked like someone he wouldn’t like. I was shocked. I started to react, and then I began to think, do I come to conclusions based on how someone looks or dresses? Had I come to some conclusions just walking in the room today?

These people we were meeting with had a history of feeling that they were not respected, not listened to, and without the power to make effective change. These feelings built up a lot of anger and frustration over the years. At the early meetings in the Diamond, we became the object of some of that. I learned a lot watching the folks at Jacobs deal with that. Gradually, it became obvious to me that unless you take the time to fully understand their feelings of rejection and lack of power, it is just impossible to understand where they are coming from.

I remember when I first went to visit Gompers before they began making changes, it was the only place I ever felt afraid in the Diamond, and who wouldn’t? There were chain link fences and police standing around. Everyone looked at me as if I was an intruder. It was really scary, and I’m sure it was to many of the students who went to school there, as well as to the faculty. But with amazing leadership, teachers, and students this became one of the most inspirational places I could visit in the neighborhoods.

A huge part of what we were all trying to do, residents and funders, was give people spaces in which they felt safe and had the ability to do the things they wanted to do for their community. Over time, meeting with residents in the Diamond and learning from them was essential in creating all that was to follow in this and all of our focus areas. It made me a better person.”

Personal Perspective:

Dwayne Crenshaw

People take a risk when they try to be genuinely involved, a risk that they will be misunderstood or that they will say the wrong thing. You don’t take that risk if you just fund something off a piece of paper.Dwayne Crenshaw, chief executive officer, RISE San Diego

“Growing up in Emerald Hills, I took community activism and leadership as a fact of life. My father was a Baptist minister, and my mother was president of the PTA at Horton Elementary School in the Chollas View neighborhood where I went to school. When I came back to southeastern San Diego after working for a couple of legislators in Sacramento, I knew I wanted to be involved in public service.

“I first met Pete Ellsworth and learned about the Legler Benbough Foundation around 2002, when I was working for the Jacobs Center for Neighborhood Innovation (JCNI) as their government relations director. Our community had been burned before by well-meaning philanthropists or government officials who came in with big promises that were never fulfilled. Some of the traditional leaders in our community, including our long-time city councilman, were skeptical of the Jacobs’ work initially, and it was my job to address their concerns.

Pete represented the Legler Benbough Foundation on the San Diego Neighborhood Funders Group. Of all the funders in the group, Pete was the most engaged. Others came for an annual gala, a ground breaking, or a ribbon cutting, but Pete was there for many meetings. He came for the cultural celebrations. He was present, listening, and engaged. He built relationships, personal and professional, with people who lived and worked in the Diamond.

When I left Jacobs to become executive director of the Coalition of Neighborhood Councils, the Legler Benbough Foundation became a direct funder of that organization as well. Years later, after I had moved on and graduated from law school, I went to Pete when Tony Young and I had an idea to start a leadership training program that would empower urban communities. One lesson that Pete and I had taken away from our work with JCNI was that we made a mistake when we failed to develop a leadership cohort from within the community to be responsible for the process of change. RISE San Diego is about addressing that gap, investing in human capacity in addition to dialogue.

From the strength of our previous relationship at Jacobs and CNC, Pete was willing to take a risk on us. The LBF was the first funder of RISE, providing $50,000 through a fiscal sponsorship even before we had received our 501(c)(3) from the IRS. With that trust and that confidence, we have secured more than $2 million more to run our programs. Pete’s advice and mentorship throughout this process have been invaluable.

RISE received a legacy gift of $700,000 from the Legler Benbough Foundation. It helps fund scholarships for fellows from the Diamond to participate in the year-long leadership training program with RISE. Pete insists, as part of the grant, that he gets to have lunch with the fellows. Pete is from a different time and a different era. I’ll confess, sometimes when he asks questions, I cringe a little bit with the way he says things. But he asks his questions honestly. There’s no racism or ill intent. He is really trying to learn.

People take a risk when they try to be genuinely involved, a risk that they will be misunderstood or that they will say the wrong thing. You don’t take that risk if you just fund something off a piece of paper. But Pete and the Benbough Foundation don’t do that. He wants to be there with you at the table. He wants the good news and the bad. I think its powerful, and I think most funders should do that.”

Case Study II Sources

Building Resident Capacity: The LBF and the Diamond Neighborhoods

“$1.3M Pledged to Local Teacher Training Program,” Fox5 San Diego, December 14, 2015, accessed October 14, 2019, https://fox5sandiego.com/2015/12/14/1-3m-pledged-to-local-teacher-training-program/.

Adrian Florido, “Top Execs Out at Major Southeastern San Diego Nonprofit,” Voice of San Diego, August 28, 2011, accessed November 1, 2019, https://www.voiceofsandiego.org/neighborhoods/top-execs-out-at-major-southeastern-san-diego-nonprofit/.

Amanda Brandeis, “San Diego’s graffiti arts park continues to change lives 20 years later,” ABC10News San Diego, May 22, 2019, accessed November 1, 2019, https://www.10news.com/news/good-news/san-diegos-graffiti-art-park-continues-to-change-lives-20-years-later.

Anne Stuhldreher, “Polishing Up the Diamond,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, 3, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 52-54.

Andrea Yoder Clark and Tracey Bryan, “San Diego’s Diamond Neighborhoods and the Jacobs Center for Neighborhood Innovation,” in Ezekiel Dixon-Roman and Edmund W. Gordon, eds., Thinking Comprehensively About Education: Spaces of Educative Possibility and Their Implications for Public Policy (New York: Routledge, 2012), 88.

Carissa Casares and Maureen Cavanaugh, “‘Rites of Passage’ Exhibit Celebrates Cultures of Southeast San Diego,” KPBS, April 4, 2013, accessed November 1, 2019, https://www.kpbs.org/news/2013/apr/04/rites-passage-showcases/.

Elizabeth Castillo and Angela Titus, “Activating the Power of Place: A Case Study of Market Creek,” The Foundation Review, 7, no.3 (2015): 8.

Heidi Echeverria, “Trauma Informed Journey-Urban Collective,” San Diego County Aces Connection, January 20, 2017.

Jennifer Vanica, Courageous Philanthropy: Going Public in a Closely Held World (Bloomington: iUniverse, 2018).

Mario Koran, “How Teach for America Did Its San Diego Homework,” Voice of San Diego, February 4, 2014, accessed October 14, 2019, https://www.voiceofsandiego.org/topics/education/how-teach-for-america-did-its-san-diego-homework/.

Ronald A. Heifetz, John V. Kania, and Mark Kramer, “Leading Boldly,” Sanford Social Innovation Review 2, no. 3 (Winter 2004), accessed November 1, 2019, https://ssir.org/articles/entry/leading_boldly.

Thomas H. Watts, “The Elementary Institute of Science, 1964-1970,” Journal of Science and Children 7, no. 8 (May 1970):164-70.